1. Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) was first identified in December 2019 [1]. Over the next few months, the disease quickly spread across the globe. On 11 March 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the COVID-19 outbreak to be a global pandemic [2]. From the earliest reports, it was clear that hospitals in significantly affected regions were inundated by patients requiring respiratory support [3]. Experience from the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak in 2002–2003 and early reports on COVID-19 suggested that exhaled air dispersion during high-flow nasal oxygen therapy and noninvasive ventilation (NIV) presented a high risk of infection for healthcare workers (HCWs). For hospitals with insufficient negative-pressure and isolation room capacity, and in the absence of other strategies to make these interventions safe, it was widely recommended that these therapies be avoided [4]. In response, several groups around the world embarked on the development of vented individual patient (VIP) hoods, which utilize (architectural) ventilation for the protection of HCWs from emissions associated with these aerosol-generating procedures [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10].

The broader potential for these hoods to reduce hospital-acquired infection (HAI) of COVID-19 has become apparent as evidence for the aerosol transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the virus causing COVID-19, has emerged [11]. Hospitals around the world have struggled with HCW infection [12], highlighting the limitations of existing protective measures against infectious airborne diseases. In this context, VIP hoods offer a novel and powerful tool to limit the spread of virus from the source (patient) and reduce the exposure of HCWs.

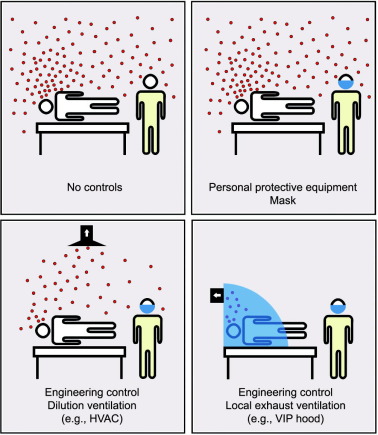

The use of (architectural) ventilation as a means of diluting and displacing pollutants has long been recognized as an effective strategy for controlling the spread of infectious airborne diseases [13], [14], [15]. In many industrial and research facilities, local exhaust ventilation (LEV) is used to ensure that workers are not exposed to toxic gases and emissions. In healthcare environments, LEV is challenging; hence, the protection of HCWs is heavily reliant on the availability, correct selection, and use of personal protective equipment (PPE), and on dilution ventilation (e.g., heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC)) and air filtration. Facilities with enhanced dilution ventilation, such as negative-pressure and isolation rooms, do provide higher levels of ventilation and/or air filtration than ordinary rooms [14], [16], [17]; however, their availability is often limited, and they do not completely separate HCWs from the airborne emissions of infected patients (Fig. 1). This leaves HCWs vulnerable to HAI from contagious airborne diseases—a weakness in existing healthcare facilities that has been clearly illustrated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Fig. 1. A schematic comparison of PPE, dilution ventilation, and LEV as controls for the protection of HCWs against airborne diseases.

Fig. 1. A schematic comparison of PPE, dilution ventilation, and LEV as controls for the protection of HCWs against airborne diseases.During—and subsequent to—the earlier SARS outbreak in 2002–2003, several researchers identified VIP hoods as a potential control strategy to reduce the extent of HAIs. In an internal report published in 2003 from the University of Hong Kong, Li et al. described a pram-style VIP hood that extended over the head of a patient’s bed†. Later, in a survey of ventilation strategies for the control of airborne infectious diseases published in 2009, Nielsen [14] identified the potential for this style of hood to enable the use of nebulizers with infected patients. In 2015, Dungi et al. [18] presented a computational fluid dynamics(CFD) study on the efficiency of a headboard extraction-style VIP hood in preventing the exposure of an HCW to cough-produced aerosols from a patient lying on a bed within the hood. The models demonstrated the effectiveness of the strategy, with no aerosols escaping from the enclosure into the breathing space of the HCW.

Based on the Hierarchy of Hazard Control, engineering controls sit below elimination and substitution, but above administrative controls and PPE [19]. Elimination and substitution are clearly not available options in the case of an infected patient; hence, engineering controls should be the primary form of protection. VIP hoods, as an engineering control, offer a more effective means of protecting HCWs than negative-pressure and isolation rooms, as VIP hoods offer the following advantages:

-

•

They can provide a physical barrier that protects HCWs from both airborne (e.g., aerosols) and projected (e.g., coughed or sneezed droplets) emissions, and reduce the spread of virus beyond the patient’s bed;

-

•

Protecting HCWs does not depend solely on the correct selection and use of PPE by the HCW and patient and, in contrast to masks, the performance of VIP hoods can be monitored and alarmed;

-

•

The HCWs can be near the patient, as long as they are outside of the enclosure, with minimal risk of infection or exposure to aerosolized medication;

-

•

The enclosure’s volume is significantly smaller than that of a room; hence, high ventilation rates can be achieved with greater efficiency (i.e., smaller fan, less energy).

While VIP hoods clearly have potential application beyond the COVID-19 crisis, for other airborne diseases such as measles and tuberculosis, it is still an immature technology and will require further development before finding widespread application in non-crisis scenarios. In this review, we explore the design and function of the various hoods described to date and identify key design challenges and performance indicators, which we anticipate will help to guide further development and inform the production of standards and codes of practice.

2. Discussion

From March to May 2020, several VIP hoods were reported in academic journals and magazines and on websites. Each of these devices, developed in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, incorporates several key features:

• The ability to isolate individual patients. While similar multi-bed enclosures have previously been described, such as those developed for use during the Ebola outbreak in 2014–2015 [20], they do not provide the same level of airborne protection for HCWs.

• The use of fans to extract air from within the enclosure and treatment of the effluent air prior to release. This feature provides protection from airborne transmission that is not provided by traditional curtain-style approaches and hoods without ventilation.

• Hood-style, partial coverage of the patient and bed designed primarily to cover the patient’s upper body and head. This approach enables the easy setup and removal of the enclosure, in comparison with full-bed enclosures such as the Trexler isolator tents. It also reduces the volume of the enclosure requiring ventilation.

Small vented and non-vented enclosures developed specifically for the protection of HCWs conducting particular aerosol-generating procedures, such as intubation, extubation, and bronchoscopy, were not included in this review, as they have been designed for different purposes [21], [22], [23].

2.1. Types of VIP hoods

Although each of the hoods incorporates the three features described above, the nature of the different designs varies.

2.1.1. Partially enclosed VIP hoods

We define “partially enclosed” to mean an enclosure that provides a physical barrier between the upper body of the patient inside the enclosure and a person on the outside. Such enclosures are not airtight and are designed to allow air to enter either through vents or through gaps, such as those around the periphery of the enclosure. One major benefit of such hoods is that they provide HCW protection from respiratory particles projected away from patients by semi-ballistic sneezes and coughs.

For these enclosures, air is typically extracted through a port, or ports, behind and/or above the patient’s head. This creates suction, and air from the outside is drawn through vents or gaps and over the patient. The resulting flow of air within the hood can be complex, with implications for the ventilation rates required for different hood designs.

We have grouped partially enclosed VIP hoods into three classes: pram-type, draped canopy, and box-type.

(1) Pram-type VIP hoods. Adir et al. [5] reported on the development of a pram-type hood to enable the safe use of NIV and high-flow nasal cannula(HFNC). When the hood is deployed, a transparent plastic canopy that is attached to the back of the bed covers the patient’s upper body, Fig. 2(a).

Fig. 2. VIP hoods. (a) Pram-type; (b) draped canopy; (c) box-type; (d) headboard extraction type. E: extraction port; F/F: filter/fan system; H/E: headboard extractor.

Fig. 2. VIP hoods. (a) Pram-type; (b) draped canopy; (c) box-type; (d) headboard extraction type. E: extraction port; F/F: filter/fan system; H/E: headboard extractor.The canopy can be retracted to allow access to the patient and for the patient to be able to easily leave the bed. A single extraction port is located above the patient’s head at the back of the enclosure. Extracted air is passed through a pre-filter and a high-efficiency particulate-absorbing (HEPA) filter before being released back into the room. McGain et al. [7] described a similar enclosure developed for the same purposes; this hood differs slightly from that reported by Adir et al., being mounted on a mobile frame that can be wheeled away from the bed. The canopy is internal to the fixed frame, which reduces the need for decontamination of the hood frame.

(2) Draped canopy VIP hoods. Several VIP hoods have been reported in which a transparent plastic canopy drapes from a polyvinyl chloride (PVC) frame over a bed, thus forming an enclosure over the upper body of a patient (Fig. 2(b)) [8], [10], [24]. Such devices, as described by Convissar et al. [10] and Patel et al. [8], use the PVC frame as ducting for air extraction. In the case of Convissar et al. [10], ports were introduced into the canopy’s rear to allow rear patient access.

(3) Box-type VIP hoods. A box-type VIP hood developed for use in Brazilian hospitals appears to have been the most widely deployed of the reported devices [9]. Named the “Cápsula Vanessa,” after the first treated patient, this VIP hood was developed by the Instituto Transire and Samel Health Tech, and the design was made freely available. This box-type hood is based on a simple PVC pipe frame with a fan and filter system attached to the outside of the hood. The frame rests on the bed, covering the upper body of the patient, and a lightweight transparent plastic canopy covers the frame (Fig. 2(c)). Unlike draped canopy hoods, which are free-standing, the frame of a box-type hood rests on the bed and must be lifted off the bed for the patient to exit the hood.

The box-type hood appears to be ideally suited to fast deployment in a crisis scenario, such as COVID-19, as it is constructed from easily available, low-cost components. However, manual handling issues for both medical workers (in accessing the patient) and patients (in exiting the hood without assistance) may limit the use of this type of hood in non-crisis scenarios.

2.1.2. Open VIP hoods

Here, we define “open” to mean an enclosure that does not provide a complete physical barrier between the upper body of the patient inside the enclosure and a person on the outside (Fig. 2). The open vented hoods that have been described to date are similar to draped canopy hoods, but do not have a canopy covering the front face of the enclosure. The major benefit of these hoods is the ease of access to the patient for HCWs and the potential for the patient to exit the hood unassisted. A key limitation is that they do not provide physical separation of patients from HCWs; hence, there is a risk that semi-ballistic sneezes and coughs from patients can expose HCWs to projected virus-bearing droplets.

Headboard extraction VIP hoods. The only open VIP hoods reported to date are headboard extraction hoods. The headboards for these hoods are located at the rear of the hood and provide extraction uniformly across the back face (Fig. 2(d)). Such an approach is designed to achieve an even flow regimen similar to a laminar air flow cabinet. This approach has the potential to minimize the dilution time for any airborne contaminants exhaled by the patient and ensures that airborne emissions flow away from the entrance to the hood.

A headboard extraction VIP hood design was developed by the US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and was made freely available [6]. One major challenge for this design is that, in order to produce uniform extraction across the headboard, a large complex surface will be exposed to contaminants, which may cause problems for cleaning and infection control (vide infra). Another limitation of this design is that it prevents access to the patient from behind.

2.2. Effectiveness of VIP hoods

Several of the reports on VIP hoods have included demonstrations of their effectiveness in protecting HCWs from airborne contaminants. Adir et al. [5]applied photometry to show that only 0.0006% of smoke particles (0.3–0.5 μm) released inside a pram-type hood passed through a filter system. Lang et al. [24]placed a humidifier inside a draped canopy hood and positioned particle counters (0.3–10.0 μm) both inside the hood and outside the hood at the approximate height of a clinician’s head. Measurements were performed with both the hood closed and fan on (at an extraction rate of 230 L∙min−1) and without the hood and fan. The particle count was found to be 18 and 700 m−3, respectively. To assess the effect of the fan, the particle count was measured inside the closed hood with and without the fan on, and the fan was found to reduce the particle count by 63%. To simulate the end of an aerosol-generating procedure, the particle count was monitored after the humidifier was turned off. With the fan on, the particle count decreased by 98% in 5 min, whereas it took 183 min to achieve the same decrease with the fan off.

The most comprehensive study described to date was reported by McGain et al. [7], who investigated the potential for a VIP hood to reduce the exposure of HCWs attending patients undergoing aerosol-generating procedures. Using an aerodynamic particle sizer (APS) spectrometer and a scanning mobility particle sizer spectrometer (SMPS) for the aerosol counts of particles > 0.5 μm and < 0.5 μm, respectively, two high-aerosol-generating procedures were identified: NIV and nebulizer therapy. The use of a pram-type hood (1.3 m3 volume) with a ventilation airflow of 40 L∙s−1 was found to reduce the aerosol count in the vicinity of an HCW attending a patient undergoing NIV treatment from 630 to 12 particles per milliliter for particles < 0.5 μm, and from 30 to 0.5 particles per milliliter for particles > 0.5 μm. For a patient undergoing nebulizer therapy, the aerosol count was found to drop from 51 000 to 570 particles per milliliter for particles < 0.5 μm, and from 1080 to 9 particles per milliliter for particles > 0.5 μm. By measurement of the aerosol count consecutively both inside and outside the hood, the hood efficiency (number of particles measured outside hood/total number of particles introduced in hood) was determined as a percentage for different particle sizes (Fig. 3). The mean efficiency over the range of particle sizes measured was greater than 98.1%; thus, the tested VIP hood provided at least the same protection to HCWs as wearing N95 masks.

Fig. 3. A VIP hood’s effectiveness against repeated nebulizer aerosol generation. Reproduced from Ref. [7] with permission.

Fig. 3. A VIP hood’s effectiveness against repeated nebulizer aerosol generation. Reproduced from Ref. [7] with permission.2.3. Ventilation of VIP hoods

As VIP hoods have not been routinely used in hospitals, guidance regarding the design of appropriate ventilation is not available. While existing hospital facilities are designed to minimize the exposure of HCWs to airborne contaminants emitted by patients, they do not provide compete isolation. Consequently, ventilation rates are specified primarily to provide sufficient dilution to prevent airborne transmission. For different hospital environments, the appropriate ventilation rate is generally recommended in terms of either air changes per hour (ACHR) or liter per second per person.

An evidence-based assessment of the safe airborne concentrations of contaminants for a disease would require many factors to be considered, including the infectiousness of the disease, the nature of the emission (rate, concentration, composition, etc.), and the effectiveness of PPE worn by HCWs and patient(s). Much of this information is not available; consequently, recommended ventilation rates are typically based on history and consensus rather than evidence [25].

For a VIP hood, the purpose of ventilation differs depending on whether the hood is open or closed. While the hood is closed, ventilation is provided to ensure that HCWs have no exposure to the airborne emissions of patients. In this case, the ventilation rate should be sufficient to prevent leakage from the hood. When the hood is open, HCWs can be exposed; hence, other factors associated with appropriate dilution within the room must be considered.

2.3.1. Ventilation rate

The effect of volume is important when determining the appropriate ventilation rate for a VIP hood. Although a hood can confine airborne emissions to within a small volume, it may—depending on the rate of ventilation—also concentrate infectious contaminants. The use of the ACHR or liter per second per person ventilation rates advised for typical rooms would lead to a significantly higher steady-state concentration of contaminants within hoods [25], [26].

When a hood is closed, the concentration of airborne contaminants inside the hood does not have an impact on HCWs. However, if the concentration is high, opening the hood to access the patient may threaten the HCW with unacceptable exposure. Two general approaches can be adopted to address this issue:

(1) The ventilation rate can be set sufficiently high so as to ensure that the steady-state concentration of contaminants resulting from a continuous source (e.g., exhalation or exhaled air dispersion during bi-level positive airway pressure (BiPAP) treatment) does not exceed a safe concentration for HCWs;

(2) The ventilation rate can be set to be sufficient to ensure that the concentration of contaminants resulting from the termination of an aerosol-generating activity (e.g., the application of a mask or ending BiPAP treatment) falls to a safe concentration within a particular period of time.

Each of these may be acceptable approaches, but each will require different protocols to be adopted. While option (1) would likely be the most convenient, as the hood could be safely opened at any time, it would require a constantly higher ventilation rate than option (2). Option (2) would require that the conditions be made safe prior to opening the hood, by both stopping the source of emission and waiting for a period of time. For option (2), different extraction rates could be applied when the hood is being prepared to be opened in order to reduce the wait period.

Clearly, the determination of the appropriate ventilation rate for a VIP hood requires several factors to be taken into consideration, including the nature of the disease and emissions, the protocols for the use of the hood, the environment outside of the hood, and the design of the hood. It is important to carefully consider the design of the air treatment systems used in VIP hoods. They should incorporate two elements: a fan for removing the air and a device for purifying the air. Such systems can be attached directly to each hood, or multiple hoods can be ducted to a single fan/purification system (Fig. 4). Mobile fan/filter systems can also be attached directly to hoods (Fig. 2(c)).