1. Introduction

Hydropower is a renewable energy source that converts the power of water into electricity through the rotation of a turbine and an electric generator. The global installed hydropower capacity in 2020 was 1308 GW, and it is expected to grow by approximately 60% by 2050 to limit the rise of the global temperature primarily caused by fossil fuels and to satisfy the energy demand. Hydropower growth would help generate 600 000 specialized jobs and would require an estimated investment of 1.7 trillion USD [1].

The hydropower sector is affected by new challenges: ① Flexibility is required to compensate for the highly variable generation of wind and solar power and to provide ancillary services, both at the daily and seasonal scales, working efficiently under off-design conditions. Pumped hydropower plants are essential to provide and consume energy on demand. ② Larger storage reservoirs are required to mitigate floods and droughts. ③ Rural electrification is also stimulating small-scale hydropower plants by powering existing hydraulic structures and small barriers, which are already serving other purposes. ④ Impacts generated by hydropower plants need to be minimized, and hydropower needs to be eco-friendly. Therefore, several emerging hydropower technologies are underway to meet these needs [2], [3], [4], [5], [6]. Novel materials can play an important role in the decrease of manufacturing labor costs, pollution, waste, and material (especially owing to the substantial weight reduction of hydro components, such as turbine runners), while improving performance and durability. However, the initial cost of some novel materials is not yet competitive owing to the high fabrication and raw material costs.

However, despite the relevance of this topic, an up-to-date scientific review of novel materials for hydropower applications has not been reported in the literature. For example, only very few reports on the development or use of composite materials in hydropower turbines have been published to date, and the few published reports are limited to either theoretical studies or very specific applications [7]. Therefore, in this document, novel materials for hydropower applications are discussed, especially those that have been introduced recently, that is, in the last decades, with some related case studies. This review is not conceived to describe and analyze traditional materials for hydropower applications, for which ad hoc references can be found in the literature.

Novel materials are categorized into the following categories: novel materials for turbines, dams and waterways, bearings, seals, and ocean hydropower. A section is provided to discuss the limitations and future perspectives.

2. Novel materials for turbines and hydraulic equipment

The turbine is the component that converts the power of water into mechanical power. A turbine is made of blades that rotate around the rotation axis when interacting with water flow. Hydraulic turbines can be classified into reaction turbines, which mainly exploit the pressure of water, and action turbines, which exploit the flow velocity, that is, the kinetic energy of water and its flow momentum. Gravity machines exploit the weight of water and are only used for very low-head applications (< 5 m) [8]. Hydrokinetic turbines exploit the kinetic energy of rivers, similar to wind turbines.

The materials commonly used for high-head turbines are austenitic steel alloys with chromium content of 17% to 20% (> 12%; the minimum chromium composition should be 12% to provide atmospheric corrosion resistance), to improve the stability of the protective film and a longer life span of the runner blades. Alternatively, the blades can be made of martensitic stainless steel, whose strength is twice that of austenitic stainless steel [9]. Low-head machines are generally made of stainless steel or Corten steel [10]. Hydrokinetic turbines are generally made of fiber glass, carbon fiber (CF), or reinforced plastics [11].

Generally, the turbines employed for high-head applications must be made with materials capable of resisting both the high stresses generated by the water pressure and fatigue, erosion, and cavitation. Low-head turbines do not experience high stresses and pressures; however, the power/weight ratio is quite small. Therefore, the principal aim of the chosen materials is to reduce their weight† and resist abrasion and fatigue. Furthermore, a large turbine weight can significantly increase transportation and installation costs, especially in remote areas. Thus, it is important to reduce the weight of the turbine to make very low-head applications more economically viable [7]. For example, in Ref. [12], the efficiency of a laboratory-scale vortex turbine increased from 33.6% to 34.8%, whereas the weight reduced from 15 to 6 kg passing from steel to aluminum. An additional benefit of weight reduction is the possibility of easing the transport and installation procedure, especially in offshore and mountainous locations.

As mentioned above, novel materials can also ensure a longer life span of hydro equipment by limiting the effects of cavitation, erosion, corrosion, and fatigue [13], [14], [15], [16]. Cavitation occurs owing to the formation of voids and bubbles, where the pressure of the liquid changes rapidly. The implosion of such voids can cause strong shockwaves resulting from the change in fluid pressure, especially in reaction turbines. Silt erosion damages components by the collision of particles on the material. Fatigue is the process of repeated cyclic stresses, for example, during load variations and vibrations. The hydropower industry is also affected by biofouling (the growth of invasive species such as zebra mussels on turbines and other structures from accumulated bacteria). Corrosion is the combined effect of oxygen and air, and it can be minimized using novel materials instead of steel. Stainless steels are complex alloys containing primarily Cr and Ni and other minor elements such as Mo, Mn, C, N, and Ti. Based on their solubility, these elements can precipitate as of secondary particles, such as sulfides, carbides, and nitrides, improving the mechanical properties and corrosion resistance of the installed components [11].

Recently, novel materials have been introduced: ① coating layers to better resist erosion, corrosion, and cavitation, and to reduce friction (i.e., related head losses), and ② structural materials to better resist loads and reduce weight [7]. Novel fabrication techniques, such as three-dimensional (3D) printing [17]‡ and surface treatments [15], are also being developed.

2.1. Novel coating materials

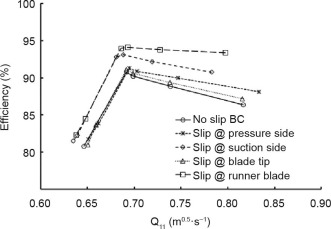

Superhydrophobic coating materials offer great opportunities to reduce surface friction [14], [18], [19]. Their application was numerically tested for a very low-head turbine [20], increasing the turbine efficiency by 4% at the design point (Fig. 1 [20]). Furthermore, superhydrophobic materials are self-cleaning, resistant to corrosion, and anti-icing [20], [21]. Similarly, the superhydrophobic lubricant fused composite prevents mussels from attaching to hydropower structures. It was developed in support of the Water Power Technologies Office, USA, and partnership with the US Bureau of Reclamation, US Army Corps of Engineers, and BioBlend Renewable Resources, USA [22].

Fig. 1. Hydraulic efficiency versus unit discharge Q11 is shown under different wall boundary conditions (BCs). Different cases are: no-slip for the entire runner, slip (i.e., superhydrophobic material) for pressure side, slip for suction side, slip for blade tip, and slip for the entire blade surface [20].

Fig. 1. Hydraulic efficiency versus unit discharge Q11 is shown under different wall boundary conditions (BCs). Different cases are: no-slip for the entire runner, slip (i.e., superhydrophobic material) for pressure side, slip for suction side, slip for blade tip, and slip for the entire blade surface [20].Coatings are also important for resisting cavitation and abrasion (especially in waters with high sediment loads). Coatings can be mainly classified into hard layers of oxides, carbides, and nitrides, soft non-metallic layers (polyurethane, epoxy, and nylon), and composite cermet coatings of hard reinforcements in tough matrix materials [15].

In Ref. [23], a review of novel coating materials for hydro turbines was conducted. Bimodal coatings with both nanometric and micrometric tungstencarbide (WC) grains, for example, WC–10Co–4Cr bimodal coatings on 35CrMo, have a better microstructure, lower porosity, higher hardness, and higher resistance to slurry erosion compared to nano- and conventional coatings. Moreover, the bimodal structure exhibited maximum resistance to slurry erosion.

In Ref. [13], novel coatings for turbines have been proposed. The use of a refinement layer of 13Cr4Ni steel for refinement led to a 2.6 times improvement in microhardness. The Ni–Al2O3 based composite coatings with 60 wt% alumina exhibited the highest microhardness and reduced erosion. High-velocity oxygen fuel (HVOF)-coated steel provides better erosion resistance than plasma nitride 12Cr and 13Cr–4Ni steels. HVOF sprayed tungsten carbide coating instead, in Ref. [24]. Plasma nitriding was found to be an excellent surface treatment to prevent wear in hydraulic turbines. It reduced the erosion rate by 96% under cavitation erosion and jet slurry erosion by 51%, whereas HVOF coating decreased the jet slurry erosion rate by up to 46%, with poor results under cavitation erosion [24]. More research should be focused on better characterization of these materials under different operations.

In Ref. [15] it has been reported that materials with altered grain size, phase content, or varied mechanical properties generate different cavitation erosion resistances; thus, advanced surface treatment techniques are under investigation, for example, friction stir processing.

Triboelectric materials that generate electricity from small-scale mechanical contacts are also under development [25]. For example, a novel organic coating triboelectric nanogenerator has been fabricated using acrylate resin (with the addition of fluorine-containing materials) as the friction layer material to improve the deficit of existing liquid–solid triboelectrification technologies (high cost, complexity, and microstructures that can be easily damaged). This coating was used to power several commercial light emitting diodes (LEDs) on a ship by collecting the wave energy during the voyage, with good output performance and stability, simple process, and low cost [26], [27]. Future applications in ocean hydropower technologies and in water wheels may be developed [28].

2.2. Novel structural materials: Composite materials

Composites have been the primary material for large wind turbine blades owing to their stiffness, high specific strength, and reasonable cost. However, they have not been extensively applied to hydropower turbines owing to the lack of research in this area. Composite materials can reduce the weight of turbine components by up to 80%. Stainless steel has a density ranging from 7500 to 8000 kg·m−3, whereas the composite material density generally ranges from 1500 kg·m−3 (e.g., CF-reinforced polymers) to 2500 kg·m−3 (e.g., glass fiber (GF), reinforced polymers) [7].

Composite materials could provide new opportunities in the hydropower sector owing to their excellent properties such as low density, high stiffness, toughness, and good fatigue behavior. Furthermore, they are resistant to corrosion and abrasion, easy to assemble, resistant to chemical agents, and can increase the life of turbine blades while minimizing maintenance costs. However, composite materials often have higher deformability, which could be a problem for high-speed rotation machines for joint and gap safety in the casing [29].

Composite materials are composed of a mixture of micro- or macro-constituents that differ in form and chemical composition and are essentially insoluble in each other, to improve material properties such as stiffness, strength, and toughness. The constituents retain their identities in the composite; thus, they do not dissolve or merge completely in each other, although they act together. Normally, the components can be physically identified and exhibit a distinct interface between one another [30]. Fiber-reinforced composites are often developed to improve the strength-to-weight and stiffness-to-weight ratios (i.e., to produce lightweight structures that are both strong and stiff). Fibers are available in three basic forms.

-

•

Continuous fibers: long, straight, and generally used parallel to each other in unidirectional layers.

-

•

Multi-directional continuous fibers: woven fabric or stitched layers, providing multidirectional strength with orientations adapted to the loading conditions.

-

•

Chopped fibers: short and generally randomly distributed (generally fiber glass).

Three main reinforcing fiber materials are available for composite materials: glass, carbon, and aramid (KevlarTM), which are typically combined with a polymer matrix. CF composites are lightweight, stiffer, stronger, and more expensive than glass. They are extensively used in aircraft structures and wind turbine blades, which are often very long (100 m) [15], [31], [32]. Both carbon and GF composites do not require expensive corrosion protection because they do not corrode and degrade like steel; however, they can undergo wet aging [33], [34], [35]. Aramid fibers such as Kevlar™ are often added as composite reinforcements to provide impact resistance [36]. However, fiber-reinforced polymers are mainly limited to applications in turbines with low rotational speeds (e.g., in ocean applications and low-head turbines), because brittle failure may occur at high rotational speeds, which could have catastrophic consequences.

The study of composite materials has been one of the major objectives of computational mechanics research in the last decade. Numerical simulations of orthotropic composite materials have been performed based on the average properties of their constituents; however, few models can work beyond the constituent elastic limit state. Thus, most procedures are limited to the numerical computation of elastic cases. Different theories have been proposed to solve this problem by considering the internal configuration of the composite to predict its behavior. The two most common theories are homogenization and mixing theories [37]. These two theories were implemented in Ref. [37] to study a hydrokinetic turbine, and it was found that runners made with composites have 5.5 times lower starting torque than the steel rotor, better performance at low water velocities, and are easier to transport, handle, repair, and start.

Some interesting examples where composite materials have been applied in high-head turbines can be found in Refs. [7], [30], [38], [39]. In Ref. [30], a Pelton turbine with 22 buckets was made using Kevlar™ 49 and chopped GFs as reinforcing fibers in an epoxy matrix. Their manufacturing process has been described, although the turbine has not been tested in terms of efficiency and lifespan. In Ref. [39] the buckets of a Pelton turbine were produced from a composite material (carbon + thermoplastic) using a 3D printer, 1/8 lighter than the steel material, and with similar strength. The material cost of the Pelton composite bucket composite was 200 EUR, whereas the unit cost of the metal bucket was 300 EUR. In Ref. [7], the authors investigated the potential of replacing stainless steel blades of a small propeller-type turbine with lightweight composite blades. A CF-reinforced thermoplastic was selected because of its lower density and smaller blade tip displacement, exhibiting the same peak efficiency as that achieved by the stainless-steel turbine. However, the composite blades were subject to a slightly higher degree of blade bending, increasing the hydraulic head. In Ref. [38], a feasibility study on 2 MW Francis turbines revealed that a composite turbine could weigh lesser by 50% to 70% than current steel versions. The weight reduction is depicted in Fig. 2, when the penstock, spiral case, guide vanes, turbine runner, and draft tube are considered.

Fig. 2. Two study cases where the weight of components is compared between composite and steel materials (adapted from Ref. [38]): (a) 2 MW turbine and (b) 250 kW turbine. 1 daN = 10 N.

Fig. 2. Two study cases where the weight of components is compared between composite and steel materials (adapted from Ref. [38]): (a) 2 MW turbine and (b) 250 kW turbine. 1 daN = 10 N.Gravity machines are also experiencing novel material developments. Carbon steel has been used for the overshot water wheel in Judenburg, Austria [40] for a 4 m head application (Fig. 3). The use of carbon steel allowed a lighter wheel to be built, whose weight of 7 kN was lower than the expected steel of 9.8 kN (estimated by applying Eq. (1)) [10].(1)where G (kN) is the weight of an overshot water wheel made of steel, H is the head (m), Q is the flow rate (m3·s−1), k = 0.15, φ = 0.151, and ψ = 2.042 are empirical coefficients for the overshot wheel, and ρs is the material (steel) density.

Fig. 3. Overshot water wheel, 4 m in diameter and 0.75 m wide.

Fig. 3. Overshot water wheel, 4 m in diameter and 0.75 m wide.High-density polyethylene (HDPE) is another material recently introduced in the low-head hydro sector. It is lighter than steel and has been used in water wheels. It is comparatively cheaper and more resistant to non-corrosive water (ocean water is an example of corrosive water). Furthermore, on-site water wheel disassembly and reassembly are easier because of the lightweight of the HDPE components [41], [42].

In July 2019, Percheron Power, with support from Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) and Utah State University’s Water Research Lab, USA, designed and tested an Archimedes screw made of composite materials and leveraging advanced manufacturing methods. It was found that light resin transfer molding exhibited lower production costs, lower waste, and emissions, and resulted in a weight lower by 25% to 30% than steel. Because the composite blades were gel-coated while in the mold, they required no primer or corrosion-resistant paints, and the corrosion and friction were reduced, minimizing friction head losses [43].

Also the ocean hydropower technology is included within the low-head context, and composite materials are used. For example, the first tidal turbine prototype, the SeaGen tidal turbine (1.2 MW of installed power in Northern Ireland [31], [44]), comprises a combination of GF and CF in a polymer matrix. The benefits were low weight and high stiffness, an effective strength-to-weight ratio, and economies of scale for complex shape manufacturing. However, the corrosion of ocean water may be a problem. Further details can be observed in the ocean hydropower section below.

3. Novel materials for dams and hydraulic structures

A dam is a hydraulic structure that intercepts the water flow of the river and generates an artificial basin upstream. When a dam is built to regulate the upstream water level of a river, without generating an appropriate artificial basin to store a significant amount of water, it is called a weir or barrier. Reservoirs are multipurpose infrastructures that are effective for flood control, irrigation, power generation, and water supply. Dam safety has improved significantly, especially since the 1990s. However, dam engineers continue to seek novel technologies to build dams that are safer, more economical, and more eco-friendly. A review of dams and their common materials can be found in Refs. [45], [46]: Arch dams are typically constructed today of mass concrete, with a relatively low cement content, whereas gravity dams are made of loose material. Dams built of loose material are called embankment dams and, in particular, earth dams or rockfill dams. As a tight element in addition to clay-silt cores, gravity dams may also have an upstream face element either of concrete (called concrete-faced rockfill dam) or a bituminous layer or even geo-membranes [46].

Recently, novel dam materials have been introduced. For appurtenant dam structures, GF-reinforced concrete is a cement-based composite with alkali-resistant GFs that are randomly dispersed throughout the product. This can be used as surface protection, for example, on spillway structures in addition to other concrete composites, having high resistance against abrasion and cavitation. The fibers support the tensile stress similarly to the steel in reinforced concrete, increasing the lifespan of the structure. The addition of conductive CFs to a precast concrete structure enables the material to provide real-time load information on the structure, thus allowing the identification of problems before stress or cracking becomes visible to the human eye [47].

Another innovation is the rock-bolted underpinning system [48]. A Global Positioning System (GPS)-guided, rock-bolted underpinning system provides a linkage to the riverbed. This leads to easier installation and fastening of the structure. Each segment is secured to the riverbed or an existing dam using multiple rock bolts, each of which can sustain large loads. Although metallic rock bolts have been used in mining for many years, they have also been applied in dams [49], [50]. In some applications, pultruded composite rock bolts may also be significant, and their light weights can reduce the environmental impact [51].

Rock-filled concrete dams are built by placing very large rock boulders from quarries in layers and then filling the voids with high fluidity and self-compacting concrete that can fill the voids easily [52]. In addition to the limitation of the thermal effects and cracking risk of concrete during construction, the advantages of rock-filled concrete include the reduction of cement/concrete quantity and the lack of need to compact the concrete. The challenge is to find adequate self-compacting concrete with high viscosity and sufficient strength. This method is an alternative to roller-compacted concrete, where dry concrete with low cement content is placed in small layers and then compacted with vibrating rollers such as soil compaction. Rock-filled concrete dams have the advantage of being overtopped without failure risk during extreme floods, and also, during construction. Thus, river diversion structures, such as diversion tunnels, can be limited. The cemented rockfill has a greater deformation modulus than the traditional rockfill material, reducing the probability of large deformation in rockfill dams, with economic benefits, and therefore limiting thermal effects during construction [53]. The concept of the cemented material dam was proposed in 2009: 10% to 20% of the cost could be saved, and the construction period could be significantly reduced. The preparation of the cemented material involves less processing, screening, grading, and mixing than concrete. The roller compacted concrete method is a recent method for building concrete dams, which has been optimized over the last decades, for example, based on the novel concept of the faced symmetrical hardfill dam and trapezoidal cemented sand–gravel dam [54]. Compared to roller compacted concrete, which uses selected cement–sand–gravel mixtures as traditional concrete, the concrete-face rockfill dams and cemented soil dams add cement to an almost untreated soil material. The lower resistance was compensated by the symmetrical or trapezoidal profiles.

The bituminous conglomerate is another trend that is being developed to cover dam surfaces [55]. Modified bitumen sealing membrane (MBSM) comprises a composite of modified bitumen and aggregates. The waterproofing action is performed by the binder stratifications of the modified bitumen sealing membrane, which are comparable to a layer of 3 cm thick in bituminous conglomerate from the resistance viewpoint to mechanical impacts [56]. However, bituminous material is limited to a certain height of a dam because the layers transform to plastic under a certain self-weight, and care should be devoted to the horizontal joint on the dam crest, that should be eventually reinforced to avoid that the layers slide downward generating creeks and infiltrations.

An important theme is the development of concrete and injection advanced technology using chemical adjuvants aim at tightening, self-compaction, viscosity reduction, improved thermal behavior, flexibility, fast placing, and crack healing. Significant progress has been made in this area over the last few decades [52].

The development of inflatable rubber weirs is also underway, especially for small hydropower sectors and head applications below 3 m. The inflatable weirs are flexible elliptical structures made of rubberized material attached to a rigid concrete base and inflated using air, water, or a combination of both. When the structure is inflated, it acts as a weir, and it can be deflated when flushing of sediments is needed. The cost is generally lower than that of common weirs of the same size [57]. Steel clapping plates were used to connect rubber bodies. However, they may corrode, and investigations of GF-reinforced polymer composites are underway to replace steel [58].

Innovative coatings and surface treatments of hydraulic structures and waterways are also under investigation. Novel coatings for waterways (e.g., penstocks) reduce surface friction and consequently increase electricity generation. A detailed review of both traditional and innovative materials [59]was published in 2016, and the key points are summarized here. The coating of concrete-lined tunnels with epoxy-based paints may reduce friction losses and prevent future degradation while lining with steel or with polyethylene reinforced by fiberglass is commonly implemented. However, although newer liners have longer lifetimes and limited maintenance, the cost of lining 1 m of the tunnel is often twice to thrice that of its excavation. Some coating materialsdescribed in Ref. [59], with related case studies, are: ① polymer-modified cement-based mortar for a 12 km-long horseshoe section tunnel with an average diameter of 9.45 m, reducing the head loss by 20% and with a cost of 30 USD·m−2; ② a latex-based primer and topcoat and an epoxy primer with added solids applied after cleaning, generating a power increase of 11%; ③ superhydrophobic materials with a related drag reduction of up to 30% and superhydrophilic surface (drag reduction by water–water interface) with drag reduction of up to 5%. These measures are of particular interest in refurbishment projects.

An additional example of a novel material for penstocks is described in Ref. [60], where steel of high tensile strength (950 N·mm−2) was used in the Kannagawa plant to reduce costs. However, brittle failures may arise, and welding is critical for the inclusion of micro-fissures. This has been extensively described in Ref. [61]. Probabilistic design methods have to be used for such high-strength steel considering imperfections in the material, especially welding.

4. Novel materials for bearings

Bearings are critical components of the hydraulic turbine units, used in supporting rotating components while minimizing friction (i.e., the need for grease) and keeping the shaft of the components aligned. The operation of hydropower turbine bearings is challenging owing to the extreme contact pressure conditions (over ∼30 MPa) over a lifespan of 40 years [62]. Hydrodynamic sliding bearings are the most used and can be classified into three major categories: journal bearings, thrust bearings, and shaft bushings[62], [63].

Friction and wear are the major factors in maintenance problems and costs. Therefore, most turbines use pressurized oil to lubricate the turbine bearings to reduce friction, wear, maintenance interventions, and costs, and to improve machine performance. However, oil leakage from hydraulic turbines may have negative impacts on the environment and some operational and maintenance problems [64]. Hence, the use of eco-friendly tribological components/technologies (e.g., bearings), known as eco-tribology, is considered as an effective engineering practice to improve the sustainability of hydropower applications [65].

To eliminate the possible danger of oil spillage from hydropower units, the concept of eco-tribology in the hydropower sector has undergone rapid development in recent years, especially in the bearing context. Water-based lubricants, ecological/vegetable lubricants, and self-lubricant bearings (with tribo-materials), with improved or similar tribological performance with respect to the traditional ones, have been developed.

Vegetable/ecological oils are biodegradable; however, they have the disadvantage of breaking down more quickly than other mineral oils when mixed with water, which affects their mechanical properties. Furthermore, they are more expensive than mineral oil, and some seal materials are susceptible to damage when exposed to vegetable oils [66]. In Ref. [67], an industrial case study is described, whereas in Ref. [66], the experience of hydropower companies with vegetable oils has been discussed.

Bearings lubricated with water operate in a boundary or mixed lubricationregime for relatively longer periods because of the low viscosity of water, especially when the low sliding speeds and start/stop cycles are considered [68]. Ingram and Ray [69] stated that water-lubricated guide bearings both contribute to increasing the overall plant efficiency by reducing friction lossesand maintenance compared to oil-lubricated ones, owing to their low cost, nontoxicity, and high heat capacity. Oguma et al. [70] described the performance of a water-lubricated guide bearing that was specifically designed for a multi-nozzle vertical Pelton turbine. However, water is a poor lubricant for severe engineering applications due to its low viscosity, solvent nature (corrosiveness), and high volatility [62]. The low viscosity can significantly increase friction and shorten the effective wear life of the bearings. Therefore, the use of water-based lubrication introduces new engineering challenges, especially the material choice for bearing surfaces that can ensure a friction coefficient below 0.1, and a lifetime of 40 years [68].

Self-lubricating bearings have been introduced to avoid the use of lubricants. They are generally made of bronze (metal-based) or Teflon (plastic-based) [63], [71]. With regard to turbines, composite materials and self-lubricating polymers are also used as thrust bearings for runners, wear plates, and trunnion bearings on spillway gates. Diamond-like carbon coating technology has also developed significantly in the last decade [65]. However, owing to the widespread of intermittent wind and solar power plants with unpredictable output, the operating conditions of hydropower plants are becoming more variable in response to the grid requirements, and self-lubricating bearings used in controlling the turbine blades and guide vanes are among the most affected components [72].

In Refs. [62], [68], examples of novel multiscale thermoplastic polymer composites are discussed for use in self-lubricating bearings. They were developed by the addition of macro- and micro-reinforcements (short carbon fiber (SCF), GF, and CF, carbon-based nanofillers (nanodiamonds (ND) and carbon nanotubes (CNTs)), and 2D materials (graphene oxide (GO), molybdenum disulfide (MoS2)) to polymers, resulting in better properties (mechanical and tribological) through a synergistic effect obtained via the multiscale mode. This reduces the need for “oil-jacking” (when high-pressure oil is injected into the gap between the bearing and counterface during start-up to separate the surfaces until a self-sustaining film can be formed) [73]. Thermoplastic polymer composites combat friction and wear issues owing to their extreme contact pressure during operation (∼30 MPa) and longevity of operation (∼40 years) [62]. The ultra-high-molecular-weight polyethylene multiscale composite with GO, ND, and SCF provided a significant reduction in friction and wear compared to pure ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene under water-lubricated conditions, whereas polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) reinforced with GF and MoS2 exhibited a lower wear rate with respect to unfilled PTFE [62].

US Synthetic is developing a novel polycrystalline diamond (PCD) bearing shaft for the RivGen Power System in a hydrokinetic context to deliver electricity to existing remote community grids [6]. Researchers at the University of Alaska, USA compared four bearing/bushing materials under a load of freshwater for 60 h, and wear (mm) measurements were performed. Fig. 4 [74] shows the benefits of the PCD bearing material compared to Vesconite™ (self-lubricated thermoplastic), a Columbia Industrial Products (CIP) marine composite with solid lubricant†, and Feroform™ (composites with PTFE) materials. The test compared wear on the far, center, and drive-side of the bearing/bushing. Through the use of PCD bearing technology in its RivGen Power System (Fig. 5), the following benefits were achieved:

-

•

A process fluid-cooled bearing-shaft assembly that: ① completely eliminated seals, ② reduced excess component weight, and ③ removed the need for contaminating lubricants and ongoing maintenance.

-

•

A diamond material that easily resists abrasive particles and the sediment flowing in water.

-

•

A sliding-element bearing surface that: ① handles higher loads, ② minimizes operational wear, and ③ delivers a lower friction coefficient (0.01).

Fig. 4. Experimental study of abrasion characteristics for critical sliding components for use in hydrokinetic devices, wear test (mm) under load over 60 h [74].

Fig. 4. Experimental study of abrasion characteristics for critical sliding components for use in hydrokinetic devices, wear test (mm) under load over 60 h [74]. Fig. 5. RivGen Power System in a hydrokinetic context (photo courtesy of Susy Kist, Ocean Renewable Power Company (ORPC), USA).

Fig. 5. RivGen Power System in a hydrokinetic context (photo courtesy of Susy Kist, Ocean Renewable Power Company (ORPC), USA).5. Novel materials for sealing

A sealing interconnects component, minimizes water leakage, and protects against the intrusion of water and dirt. The sealing of the main shaft of a turbine is the major challenge. Ideally, the sealing process should be complete; however, owing to the high costs, the primary aim of shaft sealing is limited to controlling leakage to an acceptable amount. In Ref. [75], hydropower sealing techniques were discussed.

The first hydraulic turbine used compression packing to seal the turbine shaft. However, early packing requires a significant amount of water for cooling. As compression packing devices have evolved, novel materials, lubricants, and blocking agents have been developed to extend the packing life by reducing the amount of cooling water. Several technologies have been developed over the years, including carbon-segmented rings and elastomeric radial sealing elements [75], [76]. Mechanical sealing of axial faces is becoming popular as a viable long-term sealing solution for hydraulic turbines.

Soft carbon graphite is commonly used as a sealing face and is paired with a hard-facing material (e.g., alumina ceramic). However, the thermal capabilities and pressure–velocity (PV) performance of the alumina ceramic, which acts as a very good insulator, are poor. The PV performance is evaluated by multiplying the pressure at the sealing interface by the rotational velocity of the mean face diameter of the mechanical seal. When the PV value exceeds the limit placed on the sealing face pair, the life span is reduced owing to the high wear and heat generation [76]. To overcome the PV limit, novel materials, such as SiC, have been developed, which improves the PV performance by 2–3 times, generates 60% less heat, and reduces the required cooling water. Furthermore, SiC has a very good abrasion resistance, which is a useful property for erosive waters. When compared to the carbon/ceramic face pair, a SiC/SiC face pair has a PV limit of 33% higher while generating 50% less heat [76]. The development of high-performance thermoplastic sealing materials and elastic polymers are also underway, that exhibit as much as five times the wear and abrasion resistance of traditional rubber elastomers [75]. Additional case studies on bearings and sealing can be found in Refs. [77], [78].

6. Novel materials for ocean hydropower and hydrokinetic turbines

Hydropower plants in ocean contexts convert the energy of tidal flows and waves into electricity. In the tidal context, low-head turbines exploit the potential energy of tidal ranges, whereas hydrokinetic turbines exploit the kinetic energy of tidal flows and ocean currents. In the wave energy context, hydromechanical devices convert the oscillatory motion of waves into mechanical energy [79], [80].

The ocean climate is particularly severe and variable, and seawater is corrosive. Tidal energy converters also undergo fatigue loading, whereas maintenance events have to be rare because access to submerged installations in high-energy locations is challenging. Consequently, and because local loading events such as turbulence and wave-current interactions are not yet well characterized [81], rotors tend to be overdesigned, by up to 30% in some cases, to ensure the required durability. This is inefficient in terms of material usage, cost, and performance. Therefore, novel materials with improved strength, fatigue, and anti-corrosion properties are being developed to reduce costs and increase durability. Most of the prototypes developed to date are fiber composites, such as GFs and CFs, impregnated with an epoxy resin matrix. These novel materials are mainly applicable and economical, owing to their very low rotation speed compared to hydro high-head turbines such as Francis and Pelton turbines. Epoxies are generally selected for underwater applications because, among the thermoset resin systems available, when the chemistry is optimized, they offer excellent resistance to progressive moisture absorption and hydrolytic degradation [82]. Vinyl ester resins and thermoplastic polymers were also considered. The latter provides a potential for recycling; however, it requires alternative manufacturing processes with an additional cost [83]. Table 1compares traditional materials with composite materials in the ocean hydropower context [84].

Table 1. Material properties for tidal turbines, based on Ref. [84].

| Material |

Density (g·cm−3) |

Elastic modulus (GPa) |

Tensile strength (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon steel | 7.85 | 207 | 400–500 |

| Stainless steel | 7.75 | 193 | 750–850 |

| Ti alloys | 4.50 | 114 | 1170 |

| Al alloys | 2.70 | 70 | 300–550 |

| GF composite | 2.10 | 45 | 1020 |

| CF composite | 1.60 | 145 | 1240 |