1. Introduction

On a global scale, one quarter to one third of food is lost, generating 1.3 × 109 t of food waste annually [1], [2]. In the United States, 3.84 × 107 t of food was lost in 2014 [3], while a survey of eight large cities in China found that consumers wasted 8 × 105 t of food per year [4]. For comparison, 23% of cropland fresh water, fertilizer, and land use are futilely expended to produce the fraction of food that is lost [5]. Meanwhile, the disposal and treatment of food waste is a major concern, as uncontrolled decomposition contributes to global warmingand the loss of food resources compromises sustainability [3], [5], [6]. It is also often expensive to transport and handle food waste, thus enhancing the economic advantage of onsite treatment [7]. Consequently, valorizing food loss has gained significant traction in the past decade due to the volume of waste created on a daily basis and the strain this loss places on both industry and the environment [7], [8].

Food loss from industrial processing facilities is a small fraction (5%) of total food loss but offers multiple advantages as a starting point for mitigation [1]. First, most food loss is geographically distributed; in contrast, industrial food loss is generated in high volume at specific points, which eases the capturing of its value. Second, industrial food-loss streams are relatively homogenous in nature because they are a byproduct of the specific food being processed. This homogeneity allows each food-loss stream to be targeted for unique high-value products that can economically justify the bioconversion or separation needed; in addition, in the case of anaerobic digestion (AD), it allows for onsite utilization of the generated biogas. Finally, having the means for conversion to higher value products can create market demand for the food lost on the field and post-harvest, which accounts for 50% of total food loss [1]. The inedible fraction of this upstream food loss can be valorized if combined with the downstream byproducts of food-processing facilities. In combination, these factors make industrial food loss an effective entry point to mitigate the greater food-loss problem.

Food loss is the “… decrease in quantity or quality of food,” according to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations (UN), while food waste is the subset of food loss that occurs due to the disposal or non-food use of food that is otherwise safe for consumption [9]. This paper reviews and compares the production of major industrial food-waste streams, and reports on recent progress in the end-use valorization of those streams. Specifically, we look into seven major industries—potato processing, cucumber pickling, coffee roasting and serving, pomegranate juice, citrus processing, fish processing, and cheese processing—that produce a significant volume of waste each year. First, we explore upgrading food-waste streams into higher value products using a variety of technologies. We then look at those same industries and determine the potential for upgrading the food-waste streams to methane using AD. Note that, to date, the pickle brine produced from the pickling industry cannot be processed using AD, and was thus excluded from that comparison. This paper focuses on the theoretical potential of the food-waste streams and does not take processing costs into account. This review demonstrates the significant potential for further downstream use of these often-discarded food-waste streams.

2. Methodology

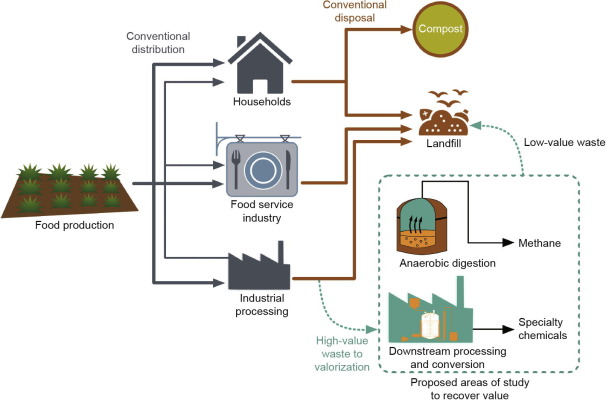

Three types of studies were examined in this literature review: ① studies that utilized waste sources generated during the industrial processing of foods; ② studies on generating a value-added product from that waste source, other than biogas; and ③ studies on developments in the value-added product that have been made in the past five years (prior work on those food-waste streams is also cited, and products where relevant). Industrial food-waste streams were chosen because they generate predictable food-waste streams that are more homogeneous than consumer food-waste streams; such predictability is needed in order to target the recovery or processing of specific compounds. Examining only those studies that fell into these categories led to a focus on seven industrial food-waste streams, which are shown in Table 1 [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], along with their general characteristics. Cucumber pickling brine is included in the review but omitted from Table 1 because its relevant characteristics do not fully align with those of the other industrial food-waste sources. This review is organized with respect to the products generated from the food-waste streams. Resource potential calculations assume full global capture of the resource, and gross profit at experimentally observed yields. Fig. 1 is included to demonstrate the flow of food from production to disposal, and is simplified in order to demonstrate both conventional disposal and where our methods fit within the scheme. Food waste generated from industrial applications can be diverted from landfills to higher value processing. After processing, some low-value waste will remain and will need to be disposed of; however, this disposal is likely to result in reduced greenhouse gas emissions since most of the complex carbohydrates will be simplified during the downstream processing.

Table 1. Characteristics of industrial food-waste streams.

| Industry | Resource | Total solids 1 | VSs | Readily degradable carbohydrate | Cellulose | Hemi-cellulose | Pectin | Proteins | Lipids | Lignin | Antioxidant | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Potato processing | Potato peels | 9% | 90% | 63% | — | — | — | 17% | 1% | 10% | — | [12], [13] |

| Coffee roasting and serving | Coffee grounds | 20% | 98% | — | 9% | 37% | — | 14% | 17% | — | — | [14], [15] |

| Pomegranate juice | Pomegranate peels | 92% | 95% | — | 5%–20% | — | 5%–11% 2 | — | — | 9% | 32% | [10], [16], [17] |

| Pomegranate seeds | 13%–19% | 98% | — | 19% | — | — | — | 12%–20% | 21% | 10% | [18], [19], [20], [21], [22] | |

| Citrus processing | Citrus peels | 19% | 95%–97% | 1% | 22%–37% | 5%–17% | 23% | 16%–23% | 1%–4% | 7%–9% | — | [11], [23] |

| Fish processing | Fish tails, skin, heads, and bones | 20%–50% | 75%–81% | — | — | — | — | 15%–30% | 0–25% | — | — | [24] |

| Cheese processing | Whey | 6% | 92% | 78% | — | — | — | 11% | 7% | — | — | [25] |

Values are shown as a percentage of total solids (dry solids), unless otherwise stated; “—” indicates value unknown; VSs: volatile solids.

- 1

-

Percentage of total mass.

- 2

-

Measured as uronic acids.

Fig. 1. Simplified flow diagram of food from production to disposal. The dotted box highlights where the current report fits within the scheme. High-value waste can be diverted from the landfill to processing to recover value. A small stream of waste will be disposed of, but should result in decreased greenhouse gas emissions since many of the complex chemicals will be reduced or removed during processing.

Fig. 1. Simplified flow diagram of food from production to disposal. The dotted box highlights where the current report fits within the scheme. High-value waste can be diverted from the landfill to processing to recover value. A small stream of waste will be disposed of, but should result in decreased greenhouse gas emissions since many of the complex chemicals will be reduced or removed during processing.3. Results and discussion

3.1. Identifying industrial food waste

Industrial food wastes are derived from various industries and are thus as varied as their sources. Fruit juice facilities often produce peels, seeds, and other organic matter as waste [10], [11], [26]. Liquid byproducts from industries, such as whey from cheese-making and brine from cucumber pickling, are also common and serve as substrates for various conversions [27], [28]. Agricultural waste, such as animal and post-harvest waste, have applications in bioenergyproduction [29], [30], [31], [32]. Although the proteins, lipids, carbohydrates, and other compounds available in food waste render it a suitable alternative to produce commodity and higher value chemicals, some challenges for each source are discussed in this section. On a global scale, 1.3 × 109 t of food is wasted annually, which amounts to approximately a third of the food produced for humans [2]. One current challenge is food-waste handling; landfills are not a sustainable solution [3], [6]. It is also often expensive to transport and handle food waste. However, onsite treatment of the waste may be economically advantageous [8].

3.2. Specialty products from industrial food waste

3.2.1. Lactic acid

The proliferation of lactic acid bacteria on food sugars has been exploited for thousands of years as a means of preserving foods [33]; however, the recent development of polylactic acid (PLA) polymers—a biodegradable alternative to polypropylene, with similar properties—has resulted in microbial fermentation being used for commodity chemical production [34]. The bioplastics industry grew 17.7% per year from 2007 to 2017, and PLA polymers sell for 1.87–2.20 USD·kg−1, a relatively high value [35], [36]. As a consequence, interest in the utilization of food waste to produce lactic acid is increasing, especially for food waste that is high in carbohydrates. Recent attention on the utilization of industrial food waste to produce lactic acid has focused on potato peel waste, but the brine from pickling operations also demonstrates promise.

Potatoes are the fourth largest starch crop in the world after rice, corn, and wheat, with 2 × 107 t of production in the United States and 9.5 × 107 t in China [9]. In the United States, 68% of the potatoes are destined for processing facilities [37]. The potato peel waste generated from this processing has been shown to be 63% carbohydrates by dry weight, with more than half of the carbohydrates being present as starch [38].

Conversion of potato peels to lactic acid has a major advantage: The process is quick, with an optimal fermentation of around 24 h [13]. However, major drawbacks have yet to be overcome. The total lactic acid concentration in the conversion product of 11.1 g·L−1 is low for industrial fermentation [2], which is likely due to the low solids-loading rates of 30–50 g·L−1 that have been used thus far [13]. In contrast, the use of post-consumer food waste containing up to 117 g·L−1 of dry carbohydrates has achieved 80–100 g·L−1 of lactic acid [39]. This discrepancy in lactic acid production is due in part to the use of added enzymes to degrade long-chain carbohydrates prior to fermentation [39]. The market potential for potato peel waste under the current technology is shown in Table 2[9], [10], [11], [13], [14], [25], [26], [27], [37], [40], [41], [42], [43], [44], [45], [46], [47], [48], [49], [50], [51], [52], [53].

Table 2. Resource potential of industrial food waste to specialty products.

| Industry | Resource | Global mass of resource (t·a−1) | Potential product from resource | Yield of potential product (kg(product)/kg(resource)) | Mass of potential product (t·a−1) | Technology required for conversion | Market value of potential product (USD·kg−1) | Potential revenue of specialty product (×106USD·a−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Potato processing | Potato peels | 25 954 386 1, 2 | Lactic acid | 0.140 3 | 3 633 614 | Fermentation and separation | 1.54 4 | 5 595.8 |

| Cucumber pickling | Pickling brine | 2 074 888 925 2, 5 | Lactic acid | 0.010 6 | 24 898 667 | Electrodialysis | 1.54 4 | 38 343.9 |

| Coffee roasting and serving | Coffee grounds | 25 570 924 7, 8 | FAMEs | 0.170 9 | 4 295 915 | Dimethyl ether extraction of oil and esterification to FAME | 0.97 10 | 4 152.6 |

| Pomegranate juice | Pomegranate peels | 1 302 500 8, 11 | Phenolic microcapsules | 0.070 12 | 91 175 | Ultrasound extraction, emulsification, spray drying | 8.00 13 | 729.4 |

| Pomegranate seeds | 370 000 8, 14 | Antioxidant oil microcapsules | 0.100 15 | 37 000 | Ultrasound extraction, emulsification, spray drying | 5.00 16 | 185.0 | |

| Citrus processing | Citrus peels | 24 204 988 2, 17 | Ethanol | 0.250 18 | 6 051 247 | Cellulose hydrolysis, fermentation, distillation | 0.53 19 | 3 180.9 |

| Pectin | 0.230 20 | 5 567 147 | Hot dilute acid treatment, alcohol precipitation | 4.00 21 | 22 268.6 | |||

| D-limonene | 0.005 22 | 139 179 | Steam distillation and alkali treatment | 4.14 23 | 576.5 | |||

| Fish processing | Fish tails, skin, heads, and bones | 540 2, 24 | Bioactive peptides | 0.730 24 | 394 | Hydrolysis and electrodialysis with membrane filtration | Highly varied 25 | — |

| Cheese processing | Whey | 150 000 000 26 | Butanol | 0.010 27 | 1 950 000 | Fermentation and separation | 0.70 28 | 1 365.0 |

| Acetone | 0.001 27 | 150 000 | Fermentation and separation | 1.64 29 | 246.0 | |||

| Ethanol | 0.001 27 | 150 000 | Fermentation and separation | 0.53 19 | 79.5 |

- 1

-

68% of potatoes produced are destined for processing [37] and 10% of mass is waste in the processing facilities [40].

- 2

-

Estimates waste specifically at processing facilities.

- 3

-

Maximum observed yield of 0.14 g lactic acid per gram of potato peel waste [13].

- 4

-

Using a value of 0.7 USD·lb–1 (1 lb = 0.4535924 kg) [41].

- 5

-

74 975 625 t of cucumbers produced globally in 2014 [9], 64% of cucumbers utilized for pickling and 40% of fermentation volume is spent brine [42], 61.67 g cucumber per metric cup (a metric cup is 250 mL) density (aqua-calc.com).

- 6

-

Maximum observed concentration of 12 g lactic acid per liter in spent pickling brine [27].

- 7

-

Assumed spent coffee grounds are 67% moisture [43]; worldwide green coffee production is 8 790 005 t [9]. Assumed roasted coffee : green coffee yield of 1 : 1.3, and a 4% moisture content for roasted beans. Assumed all solids are retained in grounds upon brewing coffee.

- 8

-

Estimates waste product produced at processing facilities as well as waste produced by individual consumers that did not buy a processed version of the original product. Data on the fraction of the agricultural product that went to processing facilities could not be found.

- 9

-

Coffee grounds are approximately 16.8% oil by wet weight, assumed 100% theoretical conversion to fatty acid methyl ester (FAME) [14].

- 10

-

Biodiesel density of 0.88 kg·L−1 [44] and price of 3.22 USD·gal−1 (1 gal = 3.785412 L) [45].

- 11

-

Assumed 0.521 t pomegranate peel per tonne of pomegranate [10].

- 12

-

Assumed yield of 0.7% peel dry weight [46].

- 13

-

Estimated value based on spot price of the antioxidant β-carotene.

- 14

-

0.148 t pomegranate seed generated per tonne of pomegranate [10].

- 15

-

Assumed yield of 10% seed dry weight [46].

- 16

-

Estimated value based on spot price of the antioxidant ascorbic acid.

- 17

-

72 253 695 t orange produced per year globally [9], 67% of oranges used for processing in 2015–2016 [47], 50% of fruit weight as orange peel [48].

- 18

-

Ethanol yield of 0.25 g per gram of biomass observed [48].

- 19

-

Ethanol price of 1.57 USD·gal−1 [45].

- 20

-

Assumed pectin is 23% of orange peel dry matter [11].

- 21

-

Pectin prices range from 4 to 10 USD·kg−1.

- 22

-

11.5 lb of D-limonene could be extracted from 1 t of orange processing waste [26].

- 23

-

Based on Indian market of 22.24 million USD per 5920 tonnes [11].

- 24

-

1.8 million pounds of trout at 30% of biomass wasted with 74% of biomass as protein [49].

- 25

-

Prices may range to 1000 USD·kg−1; however, they are too varied for a reasonable estimate [50].

- 26

-

Global production estimated from 2005 data [25].

- 27

-

Assumes 4.9% lactose (w/v), and 0.26 g butanol, 0.013 g acetone, and 0.018 g ethanol per gram of lactose [25], [51].

- 28

-

Assumes 700 EUR·t−1 and 1.22 USD per Euro [52].

- 29

-

Assumes 1350 EUR·t−1 and 1.22 USD per Euro [53].

One feature of the potato peel waste experiments performed thus far was the use of municipal sewage sludge as an inoculum. This was associated with a relatively high specific production rate of 0.125 g·(g·d)−1, compared with post-consumer food-waste fermentations [13]. Similarly, other cafeteria food-waste experiments utilizing municipal sewage sludge inoculum achieved 0.096 g·(g·d)−1, indicating that sewage sludge is an inexpensive and abundant source of microbes to enhance process performance [54]. However, a disadvantage to the use of sewage sludge inoculum is that thus far, optical purity has been low and near equal quantities of L- and D-lactic acid have been produced [13], [54]. High optical purity, typically greater than 90% L-lactic acid, is an important quality if the acid is to be used for bioplastics [34]. High optical purity has been achieved in mixed cultures through control of pH, but a relatively high pH of 8 is needed, which increases the buffering demand [55]. To produce lactic acid that can compete in the biopolymer market, it is expected that pure culture inoculum will need to be paired with the enzymatic saccharification of food-waste carbohydrates in order to achieve high yields, production rate, concentrations, and optical purity.

Thus far, research into lactic acid from food waste has incorporated primarily post-consumer food waste rather than industrial food waste, and demonstrates that the process is achievable with high heterogeneity in the waste sources [39], [54], [55]. It is expected that potato peel waste could be combined with other carbohydrate-rich industrial waste sources, or post-consumer waste, to achieve economy of scale and year-round production beyond the season for potato harvesting.

A more direct, yet underexplored, opportunity for lactic acid production from waste is through recovery from pickling brine. Typical brine contains 7–12 g·L−1of lactic acid [27]. The fermentation of cucumbers for preservation and flavor enhancement produces a high-salt (6%–12% NaCl) brine that must be discarded [56], [57]. In both the European Union and the United States, regulations have been implemented that limit brine release, with the United States also limiting chloride discharge to 230 mg·L−1 [27], [58]. Recovery of lactic acid from the brine would allow for reuse of the salty solution in subsequent pickling fermentations while avoiding large quantities of questionable discharge. The economic potential of recovering lactic acid from potato peel brines is shown in Table 2.

Electrodialysis (ED) is one possible solution for recovering lactic acid from brines; however, multiple obstacles must be overcome. First, organic matter, including bacteria, must be removed via ultrafiltration to protect ED membranes. Second, the pH of pickling brine is often below the pKa of lactic acid (3.86), causing lactic acid to be present in its undissociated form and thus leaving it unsusceptible to influence from the applied electric field [56]. Therefore, the pH must be raised to account for dissociation. Finally, the electrophoretic migration across the membrane may preferentially target the salts present in the solution, given their smaller size, charge, and high concentration. This preference would indicate that the bulk of the energy would favor separating the higher concentration salts, thereby leaving the lower concentration lactic acid in the brine solution. ED has been proposed for the crystallization of salt from the waste of reverse osmosis (RO) processes [59]. The issues with ED are not trivial. A proposed alternative to recover lactic acid from pickling brine is anion exchange. Thus far, this technique has been applied to lactic acid fermentations with exchange resins such as Amberlite IRA-400 that are highly selective to organics [60]. Without a clear indication of the selectivityof anion-exchange resins in the presence of high salt concentration, the viability of recovering lactic acid is unknown. Overall, the recovery of lactic acid from pickling brine represents opportunities for further study with marked potential environmental benefit.

3.2.2. Biofuels

Liquid biofuels are an attractive end-product for industrial food waste as there exists a broad and reliable market, and the final process of combustion can be more tolerant of chemical heterogeneity, which can occur when processing complex waste sources [61]. While both ethanol from carbohydrates and biodiesel from lipids are well-established processes, recent advances have heightened their viability to be produced from industrial food waste.

The lipid fraction of food waste is well suited for conversion to fatty acid methyl ester (FAME); however, extraction is difficult at low concentrations. Recently, dimethyl ether (DME) has been utilized to effectively extract oils from industrial food wastes [14]. This extraction technique is attractive because DME has a low boiling point (−28 °C) but remains a liquid under high pressure (e.g., 0.51 MPa at 20 °C), at which extraction occurs. Therefore, recovery of the DME can be achieved efficiently. Coffee ground oils, which are approximately 17% by weight, could be extracted with DME [14]. An economic scenario for producing FAME from coffee grounds is shown in Table 2.

DME can also be used for further extraction of oils where pressing has reached its limit of effectiveness; soybean and rapeseed cakes are both comprised of around 1% oil [14]. The DME extraction process could be applied to an array of industrial food-waste sources. For example, after fermentation of the carbohydrates in potato peel waste, the lipids are left more concentrated, at 1.4% of solids post-harvest [12]; this process could also be used for pomegranateseeds, which contain up to 20% oil by dry weight [62].

The cellulose fraction of industrial food waste also demonstrates potential for conversion to ethanol. Among food wastes, citrus peels contain high amounts of cellulose (37% for orange) with low lignin content (7.5% for orange) [48]. Fermentation inhibitors are present, including pectin (23% for orange) and D-limonene, but extracting these compounds prior to ethanol fermentation offers synergistic production of two high-value coproducts. D-limonene is associated with the citrus oils extracted from the peel, and can be used as an insect repellent, flavoring agent in food, aromatic element in cosmetics, and industrial dispersing agent or solvent [11]. Pectin is a high-value food modifier that can alter viscosity and aid in gel formation [63]. Pectin can be extracted with hot dilute acid (with a pH of about 2) and then precipitated with alcohol [11]. The economic potential of ethanol, pectin, and D-limonene from citrus-peel processing is shown in Table 2. The acid pretreatment has the added benefit of enhancing the degradation of cellulose to monomers for fermentation to ethanol; in addition, the process can be combined with steam pretreatment [64].

Readily degradable sugars from industrial food waste also demonstrate potential for conversion to butanol and coproducts, via acetone, butanol, and ethanol (ABE) fermentation. Butanol is an advantageous biofuel because it does not require engine modification to be used in conventional gasoline automobiles; it has 83% of the energy density of gasoline, compared with ethanol, which has 65% [65]. Of food wastes that are high in readily degradable sugars, the waste from baking operations and the whey from cheese-making have recently been studied.

Estimates on the quantity of bakery waste, including stale bread, inedible doughs, and batter, could not be found but are expected to be significant. In the United Kingdom for example, household waste of baked products is estimated to be 400 000 t·a−1, indicating a large industry with possibly comparable upstream waste [66]. The wastes are rich in glucose; bakery doughs, batters, and stale breads are approximately 60%–62% starch by solids [67]. Using Clostridium beijerinckii NCIMB 8052, it was shown that 0.36 g ABE per gram of substrate could be consistently achieved from dough, breadcrumbs, and waste batter [67]. Specifically, 0.19–0.21 g of butanol was yielded per gram of substrate [67].

Cheese whey is rich in lactose, which has recently been investigated for conversion to butanol. Butanol concentrations from cheese whey have ranged from 5 to 12 g·L−1 [51], [68]. Fractions vary, a 6 : 3 : 1 of butanol : acetone : ethanol ratio is common, and yields are low but comparable to other food waste, starting from 0.25 g of butanol per gram sugar, or around 0.3 g of ABE per gram of sugar [51], [65], [68].

The primary challenge in converting food waste to butanol is the same as that in producing butanol from other products: low fermentation concentration (< 30 g·L−1) due to product inhibition [65]. This in turn leads to challenges in separating the butanol, due to its high boiling point (117 °C) and low vapor pressure (2.3 kPa) [65], [67], [68]. These characteristics enhance the safety of pure butanol, while limiting its distillation efficiency for recovery. To overcome product inhibition, simultaneous separation and fermentation have been proposed, with pervaporation and adsorption being the least energy-intensive separation options [65].

Overall, techniques for producing biofuels from industrial food waste demonstrate the potential to connect waste sources to a dependable market. Furthermore, a combination of extracting both lipids and carbohydrates is often synergistic and offers outlets to both biodiesel and bio-alcohol markets.

3.2.3. Antioxidants and phenolics

Antioxidants and phenolics are high-value compounds that can enhance the viability of the bioprocessing of food-waste streams. Both can be considered part of a high-growth nutraceuticals market—worth between 100 billion and 200 billion USD per year—with recent growth near 7% per year [69]. Furthermore, some antioxidants can be utilized as a natural preservative for applications such as extending the shelf life of food oils [70].

Extraction of antioxidants from citrus peels could further enhance ethanol production and result in a much higher value coproduct. Citrus peel antioxidants have been shown to inhibit carcinogenesis [71]. These antioxidants are extracted via methanol [71]. Similarly, flavonoids have been shown to exhibit anti-inflammatory properties, and can be extracted via hot alkali treatment [72].

Discarded pomegranate peels and seeds are another potential source of antioxidants. Pomegranate seed oil has been shown to contribute antioxidants with immune-boosting properties, while the peels are high in antioxidants in the form of phenolics [46]. Both pomegranate seeds and peels can be separated by treatment but treated through similar processes of drying, grinding, ultrasound-assisted solvent extraction, filtration, drying, emulsification, and spray drying [46]. By means of this process, seed oil microcapsules could be produced at a yield of 10% of dry seed weight, while a yield of 0.7% of high phenolic microcapsules could be generated from peels [46]. The economic potential of these two resources is shown in Table 2.

Similarly, spray drying can be used to recover phenolics from olive-mill waste waters. Olive-mill waste can be processed into multiple coproducts in a proposed scheme that can concentrate the liquid fraction of olive-mill waste, and that encapsulates the phenolics via spray drying. The encapsulated phenolics can be used as a food supplement, although this process has not been fully prototyped [46]. A portion of the process that has been further evaluated involves utilizing the olive-mill waste solids to generate an olive paste spread via fermentation, or by spray drying the solids to produce an olive powder. This powder can be used as a cholesterol-lowering agent, a food additive, or in cosmetic products. The spread is made by recombining fermented solids with olive oil, vinegar, peppers, and herbs [46].

Overall, antioxidants and phenolics are part of a growing market. Their use and efficacy are still under investigation, and the extraction of valuable products from industrial food-waste processes is an area of active research and development.

3.2.4. Bioactive peptides

The fishing industry catches and farms 1.54 × 108 t of live fish per year [24]. In certain regions, 70% of the fish is processed prior to sale, and 20%–80% of the fish mass (head, tail, fins, entrails, and frames) ends up as waste, depending on the processing method and the type of fish [24], [73]. This food-waste stream has established utilization as fish silage, fish meal, and fish oil, which are predominantly used for animal feed. Fish silage, which is produced through enzymatic and acid degradation of the fish, is a low-value product at 0.3 USD·kg–1 [74]. Fish meal, which has a lower water content, is approximately 1.6 USD·kg–1 [75]. However, renewed interest in bioactive peptides for the treatment of infection, diabetes, and hypertension has enhanced the focus on fish waste due to the high concentration of proteins in fish waste; mixed fish waste has been reported to contain 58% crude protein [76], [77]. These health applications of fish waste have greater barriers to market, but also provide orders-of-magnitude higher value. Recent advances in separating bioactive peptides have enhanced the potential of this resource.

Combining ED with ultrafiltration membranes (UFMs) in order to separate bioactive peptides from the enzymatically hydrolyzed waste of rainbow trout, a freshwater fish commonly produced in the western United States, is one recent advancement in fish-waste utilization [49]. The market potential of rainbow trout waste is shown in Table 2; however, the potential of the broader fish-waste market is much larger, as stated above. The ED and UFM device is set up with adjacent compartments divided as follows: anode, anion-exchange membrane (AEM), UFM, cation-exchange membrane (CEM), and cathode. Electrolyte solutions are fed between the anode and AEM, and between the CEM and cathode. Meanwhile, fish protein hydrolysate is fed either between the AEM and UFM to separate out anionic peptides, or between the UFM and CEM to separate out cationic peptides, while potassium chloride is fed into the alternate compartment. Membrane configuration permits the separation of proteins based on charge, which is an important factor affecting peptide bioactivity. The process is selective; over the course of 4 h, close to 1% of the peptides migrate from the fish protein hydrolysate to the anionic or cationic chambers, indicating opportunities to pair ED with other protein hydrolysate utilization technologies. The process consumes 116 W·h per gram of cationic peptide separated, and 219 W·h per gram of anionic peptide separated at an electric field strength of 11 V·cm−1. The separated fractions were shown to have a concentration of 156 and 85 µg·mL−1 for cationic and anionic peptides, respectively [49]. Although these concentrations are dilute, they represent specialized peptides with common characteristics that are open for further study. Similarly, the combination of ED and UFM has been applied to rapeseed protein hydrolysate [78]. Overall, the combination of ED and UFM for rainbow trout offers promise as a means of utilizing the globally dispersed high mass of fish-waste production for an array of high-value applications.

3.3. Electricity and power generation from industrial food waste

AD is a technology that is often used in wastewater treatment and in the conversion of organic waste matter into biogas [2], [7], [79]. Anaerobic sludge from waste treatment plants is used as seed sludge in many studies [80]. AD typically occurs in either a single-stage digestion or two-stage digestion [80]. Single-stage AD is more commonly applied for the treatment of municipal solid waste, including food wastes. In single-stage AD, all four stages of the process (hydrolysis, acidogenesis, acetogenesis, and methanogenesis) occur within a single reactor [80]. This process can undergo either wet AD, in which the waste is processed as-is, or dry AD, in which the water content is reduced to approximately 12% prior to digestion [80]. Two-stage AD can produce hydrogenand methane in separate reactors, as the first two steps (hydrolysis and acidogenesis) occur in the first reactor, followed by the second two steps (acetogenesis and methanogenesis) in the second reactor [80]. In two-stage AD, recovery of methane as high as 90% can be observed [80]. Uçkun Kiran et al. [80]studied four different reactor types that are used in AD: packed-bed reactors (PBRs), up-flow anaerobic sludge blanket reactors (UASBRs), continuous stirred tank reactors (CSTRs), and fluidized-bed reactors (FBRs). The PBR was capable of degrading organic material at a faster rate, while the UASBR achieved 93.7% chemical oxygen demand (COD) removal and 0.912 L methane per gram of COD. The CSTR and FBR both produced biogas of which 60% was methane, although the FBR was more stable [80].

An earlier study investigated the pilot-scale production of methane from municipal food waste [81]. The rate of biogas production reached 236 m3·d−1, of which 60%–70% was methane [81]. One key outcome of this study was that the system remained stable despite fluctuations in organics loading, which suggests that AD can serve as a viable option for the conversion of food waste into biogas and methane for energy [81]. The remainder of Section 3.3 focuses on the use of AD to convert industrial waste into a single major product: methane for electricity and power generation.

3.3.1. Potato peels

The high volume of potato peel waste produced globally renders it a suitable waste product for the anaerobic production of methane. Table 3 [7], [10], [24], [25], [43], [45], [82], [83], [84], [85] shows the potential for methane production from potato peels. Although acetic acid, along with other volatile fatty acids(VFAs), is formed during potato peel digestion, none of the tested conditions resulted in VFA concentrations high enough to inhibit methane production [82]. Interestingly, potato peel residue from lactic acid fermentation can also be used in AD to produce methane using sludge as inoculum [82]. The residue has similar moisture and volatile solids (VSs) content to untreated potato peels [82]. However, the methane yield is 14% higher, with lower resulting VFA production, indicating the viability of combining lactic acid with methane production for value-added processing of potato waste. By assuming a 2 kW·h generation of energy per cubic meter of methane, a potential 1.2 × 1010 kW·h of energy can be procured globally from potato peels alone [82], [86].

Table 3. Methane production potential from industrial food waste.