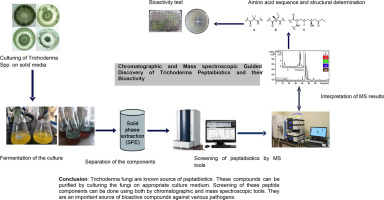

Graphical abstarct

Keywords

1. Introduction

The genus Trichoderma represents one of the most diversified groups of free-living filamentous fungi in the family Hypocreaceae, commonly found in all types of soil. These fungi have been developed as biocontrol agents against several fungal diseases [67]. Their diverse metabolic capabilities enable them to produce various bioactive secondary metabolites with significant applications in agriculture, health, industry, and the environment [1,106]. These bioactive compounds have demonstrated antibacterial, antifungal, and antiviral properties [91]. Peptaibiotics are among the non-ribosomal polypeptides found in Trichoderma, consisting of 4–20 residue peptides (500–2200 Da) with α-aminoisobutyric acid (Aib) and other noncanonical amino acids frequently occurring in the main peptide chain [121]. They possess an acylated N-terminus, while the C-terminus may include a free or methoxy-substituted 2-amino alcohol, amine, amide, free amino acid, diketopiperazine, or sugar alcohol [27,106].

Peptaibiotics consist of two main sub-classes: peptaibols and lipoaminopeptides[106]. Peptaibols are structurally distinctive peptaibiotics that typically consist of amino acid chains ranging from 5 to 20 mers [27,59,123]. They contain a high proportion of non-proteinogenic α, α-dialkylated amino acids, such as 2-aminoisobutyric acid (Aib) and isovaline (Iva), as well as an acetylated N-terminus. Additionally, they include 1, 2-amino alcohols such as Leuol, Valol, Pheol, Tyrol, Ileol, Alaol, and Prool at the C-terminus [29]. The peptide backbone is typically dominated by α-aminoisobutyrate (Aib) compared to other non-proteinogenic amino acid residues. This dominance imposes significant conformational constraints on the backbone, facilitating the formation of a right-handed α-helical structure [9,66]. Peptaibols are produced by most Trichoderma species, and alamethicin F30 was the first peptaibol reported from T. viride [14,27,69]. However, the strain was later identified as T. arundinaceum, a species belonging to the Brevicompactum clade [29,59]. The other subfamily of peptaibiotics containing lipoaminoacids among the general non-proteinogenic amino acids was named “lipoaminopeptides” [27].

Based on their chain length and sequence alignment, peptaibiotics are categorized into three subclasses and nine subfamilies (SF1 to SF9) respectively [22]; 1) long-sequence peptaibols consist of 18–20 amino acid residues with a high content of Aib, 2) short sequence peptaibols having 11–16 residues long and several Aib-Pro motifs, and 3) lipopeptaibols consist of either 7 or 11 residues, characterized by a significant amount of glycine, C-terminal amino alcohol, and an N-terminal acylated by an 8-10 carbon linear fatty acid [37]. The 9 subfamilies (SF1-SF9) are classified based on sequence alignment, structures, and specific amino acid compositions [22]. Among these subfamilies, SF1, SF4, SF5, and SF9 belong to Trichoderma fungi [106]. SF1 is the largest SF (17–20 residues) and is characterized by the prevalence of Gln, mostly at positions 6 or 7. Gln or Glu residues are commonly found at the C-terminal end, while Aib-Pro motifs frequently occur at positions 13 or 14. A Gln-Gln or Glu-Gln pair typically exists at the 18th or 19th positions. Sequences in this subfamily commonly feature Gln predominantly at the 6th or 7th positions, Aib-Pro bonds in the middle, and Gln or Glu at the 18th or 19th positions. Shorter sequences usually contain only a single Gln residue [22]. These sequences are characterized by the frequent presence of Aib, suggesting the formation of α-helical structures. SF4 members differ significantly from other subfamilies, containing either 11 or 14 amino acids. They contain a conserved Gln or Asn residue at the 2nd position. The 11-residue members have two Pro at positions 9 and 13, whereas the 14-residue members have three Pro at positions 5, 9, and 13. SF5 peptaibols are short and referred to as Gly-rich, containing either 7 or 11 residues. Their sequences never include Pro, Gln, or any charged residue. SF9 comprises the smallest peptaibol with 5 residues, namely trichopolins I, II, III, IV, and V. These sequences differ significantly, preventing their classification into any other subfamilies [22,106].

The amphipathic nature of peptaibiotics enables them to self-associate into oligomeric ion-channel assemblies that span the width of lipid bilayer membranes [22]. This bilayer membrane pore-forming and destabilizing behavior exhibited by many of these compounds contributes significantly to their potent antimicrobial and cytotoxic activities. Their action is particularly challenging for pathogens and tumor cells to develop resistance against [86,106,116,120]. The physicochemical and biological properties of peptaibiotics also render them effective as antiviral, anti-tumoral, and antimycoplasmic agents [78,106]. Furthermore, when they act synergistically with cell wall-degrading enzymes, they function as elicitors in plant defense mechanisms. They induce local or systemic resistance in plants against microbial invasion. These activities trigger a cascade of plant antifungal proteins, such as chitinases and glucanases, in response to the impending attachment of the pathogen [41].

The process of discovering and identifying peptaibiotics involves a sequence of steps. It begins with cultivating and fermenting fungi on solid media, followed by the extraction of peptaibols either from the culture medium or the mycelium using organic solvents. Purification and enrichment of peptaibiotics can be achieved through liquid chromatography (LC) employing polar or nonpolar stationary phases. Various detection techniques such as ultraviolet (UV) and mass spectrometry can be utilized [106]. This review aims to summarize available data on cultivation techniques, extraction and purification methods, chemical profiling techniques, structural diversity, and the biological activity of peptaibiotics discovered from Trichoderma fungi species.

1.1. Cultivation of Trichoderma for peptaibiotic production

The optimization and formulation of nutrient media and culture conditions represent critical steps in the production of novel compounds from Trichoderma fungi [105,109]. However, the selection and optimization of a medium can vary depending on the specific Trichoderma species. Efficient production and purification of surface-active compounds necessitate an optimal culture medium and growth conditions, which are crucial for characterizing the structure and function of novel compounds. The screening of peptaibiotics from Trichoderma spp. generally follows similar procedures, except for a few specific groups of Trichoderma. This process often involves growing mycelial cultures on solid-phase or broth media and subsequent extraction using various organic solvents from the ferment [7,11,20,120]. Culture conditions, such as temperature, pH of the media, fermentation cycle, and aeration, are typically controlled. In most laboratories, preparing a seed culture in appropriate nutrient media is a prerequisite for large-scale cultivation of the desired Trichoderma strain and the production of sufficient bioactive compounds. Fermentation is carried out by incubating the culture under consistent illumination, agitation, and aeration at temperatures ranging from 25°C to about 30°C. The pH of the medium is maintained between approximately 5.8 to 7.0 for an adequate growth cycle [114]. The production of peptaibols and lipopeptaibols using this method depends on various fermentation factors, such as nutrient composition (carbon and nitrogen sources), inoculum size, incubation and fermentation temperature, pH, initial moisture content, and culture oxygen levels [110,111,114]. Analytical cultivation of Trichoderma fungi and the production of peptaibols and lipopeptaibols can be achieved using diverse nutrient media, including potato dextrose agar (PDA), malt extract agar (MEA), peptone yeast glucose (PYG), dextrose casein agar (DCA), Trichoderma-selective agar medium (TSM), and Sabouraud medium (Difco Sabouraud agar). Additionally, the addition of small amounts of inorganic salts, such as MgSO4, FeCl2, MnSO4, ZnSO4, KCl, K2HPO4, KNO3, Ca(H2PO4)2, CuSO4, and FeSO4 can significantly enhance the cultivation and production of these compounds [21,28,34,50,56,57,65,114,121].

1.2. Isolation and Purification of Peptaibiotics

Fermentation of fungi under suitable culture mediums and conditions stand as a crucial step for successfully isolating and purifying bioactive compounds. This process typically involves a series of steps, beginning with compound extraction from the culture medium or mycelium, followed by purification from matrix components, analyte enrichment, and eventual chromatographic separation. Peptaibiotics purification and separation entail the utilization of diverse chromatographic tools and solvents based on polarity. Notable methods include open column chromatography (OCC), vacuum liquid chromatography (VLC), high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), gel filtration chromatography (using Sephadex LH20 with MeOH as the eluent), adsorption chromatography (using SiO2 with CH2Cl2/MeOH as the eluent), and semi-preparative reversed-phase HPLC (employing methanol/water as the eluent) [6,24,106]. Combining these techniques with various extraction procedures further enhances the process. For instance, Amberlite XAD-2 column chromatography using methanol (MeOH) and acetone as eluents, silica gel chromatography conditioned with chloroform (CHCl3) and (MeOH), and reverse-phase (RP-C18 or RP-C8) cartridges with MeOH and water as eluents have been used for isolating trichodecenins and profiling trichorzianines [37,106]. Other methods, such as single-step offline vacuum liquid chromatography (VLC) with dichloromethane/ethanol mixtures as eluents and diol-phase gel chromatography, have also proven effective for extraction and purification of peptaibiotics [56,72]. The selection, application, and underlying principle behind the separation techniques depend on factors such as molecular size, adsorption to the stationary phase, polarity, solubility of the mobile phase or analyte, and the hydrophobic and hydrophilic interaction between the solute and resin surface [55]. Various chromatographic techniques are commonly used for both quantitative and qualitative analyses of bioactive compounds extracted from diverse biological samples, including fungal samples.

1.2.1. Thin layer chromatography (TLC)

TLC is a cost-effective and rapid technique used for separating and analyzing compound mixtures in samples, devoid of the need for sophisticated instrumentation. While crucial for identifying the chemical nature of peptides and monitoring the number, progress, quality, and purity of raw peptide extracts within mixtures, TLC has limitations in terms of resolution, sensitivity, selectivity, and sample capacity [102]. The process involves a glass plate coated with silica of varying thickness where samples are loaded and a solvent is allowed to run through for identification. These results in the creation of TLC bands, which are visualized under UV light or other non-destructive techniques based on the sample type. Subsequently, compounds separated on TLC plates can be scraped or further extracted using solvents [99]. TLC separates compounds with different properties by leveraging diverse interactions between solutes, the sorbent (silica), and the mobile phase [98]. In the context of peptaibiotics, TLC is commonly employed to detect, identify, and monitor their formation during Trichoderma culture fermentation, in conjunction with multiple separation techniques [49,80]. For instance, within the suzukacillins peptaibiotics (SZ-A and SZ-B) derived from T. viride strain 63 C-1, TLC was instrumental in distinguishing between the two microheterogeneous [95].

1.2.2. Column chromatography

Column chromatography stands as one of the most valuable methods for separating and purifying both solids and liquids, particularly in small-scale experiments. This technique facilitates liquid/solid (adsorption) or liquid/liquid (partition) separation. In this process, a vertical glass column contains the stationary phase, typically a solid adsorbent, where the mobile phase and sample are introduced from the top and allowed to flow down through the column using either gravity or external pressure. It plays a vital role in separating individual mixtures of molecules like sugars, proteins, and other substances, essential for subsequent experimentation [70]. Macroporous resin chromatography is particularly important for efficiently separating lipopeptide mixtures into distinct families by employing a straightforward stepwise solvent gradient elution under optimal conditions [51]. The properties of the resin, such as particle size, pore diameter, surface area, and polarity, dictate the separation of bioactive compound mixtures.

Various column chromatographic techniques are employed in peptide separation, including liquid chromatography (LC), high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), and reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC).

Liquid chromatography (LC) stands as the primary technique for efficiently separating and isolating similar or dissimilar compounds. The interaction between the sample mixture and the stationary phase packed in a column determines the separation of each component. Compounds with a stronger interaction with the stationary phase remain in the column longer than those with weaker interactions, thus leading to their separation. Individual chromatographic peaks represent distinct molecules at specific retention times, while the peak height and area directly relate to the concentration of the compound present in the mixture [23].

The demand for enhanced resolution and faster separation in liquid chromatography (LC) has led to the evolution of high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), subsequently followed by ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography (UHPLC). This specialized form of column chromatography finds utility in separation, biochemical analysis, identification, quantification, and purification of complex and clustered surface-active compounds from biological samples. These techniques are particularly valuable in identifying proteins and their peptide fragments, offering significant improvements in speed, resolution, and sensitivity. This is achieved through the utilization of stationary phases comprising very small and uniform porous particles with high ligand densities, operated at pressures of up to approximately 15,000 psi [13,46,115]. HPLC and UHPLC can be operated in either normal phase or reversed phase models [14,23]. Normal phase liquid chromatography (NPLC), encompassing both HPLC and UHPLC, involves a polar stationary phase that interacts strongly with solutes compared to the non-polar mobile phase. Initially, non-polar solutes elute first, based on the composition and ratio of polar and non-polar solvents, followed by the elution of non-polar solvents [14,68]. The commonly used stationary phase for HPLC separation is ODS (octadecylsilane), consisting of C18, C8, and C4 alkyl chains covalently bonded to silica particles [55]. The C-18 column, mainly employed for polypeptide separation, varies in length from 150 to 250 mm depending on the desired resolution and separation [118,127]. HPLC's resolving power makes it ideal for the rapid processing of multi-component samples on both analytical and preparative scales, utilizing water/acetonitrile (MeCN) or methanol/water gradient solvents. It serves to identify, quantify, and purify individual components of peptaibiotics mixtures from samples at different wavelengths using a detector [96]. For instance, the HPLC separation of 20-residue peptaibols (Longibrachins LGB II and LGB III) from T. longibrachiatum involved a liquid chromatograph using a semi-preparative reversed-phase C18 column with MeOH-H2O-trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) as the eluent [58]. Similarly, two peptides subfractions, namely TVA and TVB, were obtained from T. virens strain TV29-8 culture filtrates using exclusion chromatography and silica gel chromatography. The elution system employed MeOH-H2O, with the separation leading to six main peaks in the TVB group. This mixture was further analyzed by semi-preparative HPLC, yielding TVB I to VI peptaibols. Subsequent spectral analysis revealed TVB I, II, and IV as homogeneous Trichorzins peptaibols, while TVB III, V, and VI remained a mixture of peptides [124].

RP-HPLC is widely recognized and preferred due to its versatility in applications and the availability of diverse mobile and stationary phases. In contrast to Normal Phase Liquid Chromatography (NPLC), RP chromatography involves using a nonpolar stationary phase in conjunction with a polar mobile phase, typically a blend of water and an organic solvent miscible with water. This technique's online coupling with sample preparation and detection units, particularly MS, renders it an ideal choice in proteomics research [3]. RP-HPLC finds extensive use in isolating, separating, structurally characterizing, quantifying, and purifying peptaibiotic components from various representative strains of Trichoderma fungi [6,17,18,48,49,90,94]. For instance, lipopeptaibols were purified and analyzed using reversed phase (RP)-HPLC with UV detection at 226 nm on semi-preparative C18 columns [74]. Similarly, cytotoxic lipopeptaibols (lipovelutibols A−D) from T. velutinum fungi were purified through semi-preparative RP-HPLC using a Reprosil Gold C18 column. Elution was performed using acetonitrile-water and methanol-water gradients at different proportions, monitored at 214 nm [106]. Moreover, an analytical Vydac Protein & Peptide, C18 platform was employed for detecting peptaibols from T. asperellum TR356 extract chromatogram. This method utilized gradient elution of MilliQ water with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) and acetonitrile with 0.1% TFA, monitored by UV detection at 216 and 280 nm[15].

1.3. Mass spectroscopic guided discovery and profiling of peptaibiotics

Mass spectrometry has emerged as a formidable tool for identifying and profiling polypeptide antibiotics from various biological samples [19]. In previous years, spectroscopic tools such as field desorption (FD), fast atom bombardment (FAB) MS, Ion Spray Ion Trap MS (ISI-MS), and Electrospray Ion Trap MS (ESI-MS) were employed for peptide molecule and peptaibiotics identification [26,45,49,83]. Presently, high-throughput and efficient spectroscopic tools like Matrix Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization-Time of Flight MS (MALDI-TOF-MS), liquid chromatography electrospray ionization quadrupole time of flight tandem MS (LC/ESI-QTOF MS/MS), Ultra High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (UHPLC) coupled with QTOF instrumentation, and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) are widely utilized for investigating, detecting, evaluating, and analyzing biochemical properties, including peptaibiotics [4,13,25,51,87,111].

These tools have proven highly effective in determining molecular mass and structural information of peptides and proteins. Mass spectrometry aids in peptide identification by analyzing the mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) of ions, generating a mass spectrum from the plot of ion abundance versus m/z. Additionally, MS and tandem MS (MS/MS) techniques have significantly contributed to determining amino acid sequences and elucidating primary structures of peptides, even in complex mixtures. However, certain biomolecules cannot be ionized by the 'classical' electron ionization (EI) technique, typically used for volatile molecules, limiting its application to thermally stable compounds with low molecular weights [100]. The development of 'soft-ionization' techniques like electrospray ionization and matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization has addressed this limitation. Nonetheless, MS cannot accurately determine peptaibols containing high numbers of isoform amino acid sequences such as leucine (Leu)/isoleucine (Ile) or valine (Val)/isovaline (Iva). Resolving such complexities often necessitates a combination of different spectroscopic tools and chemical derivatization methods. High-resolution electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (HRESIMSn) and 1D and 2D nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) are typically used to identify amino acid compositions and sequences.

Determining the absolute configuration of each constituent amino acid involves techniques such as Marfey's method [44]. The process begins with acid hydrolysis followed by derivatization using Na-(2, 4-dinitro-5-fluorophenyl)-L-alaninamide, commonly referred to as Marfey's reagent. Comparison of the retention times between amino acid-Marfey's derivatives and derivatized D and L standards for each amino acid is performed using LC-UV at a wavelength of 340 nm [94]. This method is pivotal in assigning absolute configurations to amino acids. To enhance accuracy and reliability, High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry (HRMS) and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) are integrated into Marfey's analysis, providing corroborative data and mitigating uncertainties associated with UV data alone. Moreover, in scenarios where Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry (ESI-MS) fails to differentiate Val/Iva, Val-OH/Iva-OH, Leu/Ile, or Leu-OH/Ile-OH, Gas Chromatography Mass Spectroscopy (GC-MS) proves to be a valuable alternative for analyzing derivatized amino acids [72]. Each spectroscopic tool used for peptide analysis holds specific advantages and limitations. Optimal selection of techniques and devices hinge upon factors such as solubility, charge, stability, and molecular size of the target compound.

1.3.1. FD-MS and FAB-MS

Fast atom bombardment (FAB), introduced as a pivotal technique for ionizing polar and non-volatile molecules normally unresponsive to electron ionization, has found extensive application in the realm of peptides and proteins [8]. The utilization of tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) combined with FAB has enabled the molecular identification of biochemical molecules and amino acid sequences in peptides [26]. Field desorption (FD) and fast atom bombardment (FAB) mass spectrometry (MS) have also successfully facilitated direct structural analysis of synthetic and biological polypeptides, as well as various peptide metabolite conjugates [30,38,83]. HPLC coupled with FD-MS and both positive and negative ion FAB-MS offers a highly sensitive and universal method for directly resolving and characterizing peptaibol components. Definitive structures of peptaibol antibiotics from different representative strains of Trichoderma fungi, exhibiting pronounced micro-heterogeneity, have been characterized using HPLC, FD-MS, and particularly FAB-MS. HPLC serves the purpose of investigating and isolating components, determining constituents, and quantifying relative amounts of polypeptides from Trichoderma fungi. Conversely, FD-MS and FAB-MS are used to evaluate individual molecular masses of each compound. Additionally, the combination of FAB-MS with selective acidolysis at the preferential cleavage site aids in sequencing and analyzing the isolated components [19]. For instance, FD-MS and FAB-MS have confirmed the structural identity of various peptaibols such as samarosporin, stilbellin, and emerimicini [18].

Positive ion FAB mass spectroscopy is used for sequence analysis and molecular formula determination of 11-residue Trichogin A IV (GA IV) lipopeptaibol isolated from T. longibrachiatum. It is characterized by two pseudo molecular ion species, (M + Na) + at m/z 1088 and (M + K)+ at m/z 1104 with a molecular weight of 1065 and molecular formula of C52H95O12N11. The amino acid sequences of this compound were also determined as X-Aib-Gly-Leu (Ile)-Aib-Gly-Gly-Leu (1le)-Aib-Gly-Leu (Ile)-Leuol, which was assigned from Acylium fragments at m/z 949, 836, 779, 694, 581, 524, 467, 382, 269, 212, and 127 Da [6]. Similarly, the amino acid sequence and molecular structure of several peptaibols synthesized by various species of Trichoderma fungi were determined using FAB-MS and FAB MS/MS [25,92].

1.3.2. MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry

Matrix Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization-Time of Flight-Mass Spectrometry (MALDI-TOF-MS) has become widely adopted in proteomics due to its high mass accuracy, resolution, excellent sensitivity, and high throughput capability. Its precision in mass analysis and low detection limit are especially valuable in identifying low-abundance proteins [52]. To obtain a well-defined peptide mass fingerprint, necessary for maximum fragments derived from the original protein, a tiny amount of fungal mycelia is directly spotted on the MALDI-TOF sample plate and overlaid immediately with a matrix solution. Each sample is then ablated with laser energy, producing ions via pulsed-laser irradiation. MALDI-TOF-MS spectra, recorded in positive ion mode within an m/z range of 500-2,500, monitor the production of peptide secondary metabolites. The resulting ions are vacuum transferred for mass analysis, followed by an MS spectra-based dereplication process to identify strains with unique MALDI-TOF-MS fingerprints [39]. Various matrix compounds like trans-2-[3-(4-tert-butylphenyl)-2-methyl-2-propenylidene] malononitrile, α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid matrix (α-CHCA), 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid (DHB), sinapinic acid (SA), and a mixture of DHB-CHCA are used for MS analysis of intact peptides. These matrices absorb the laser's wavelength and indirectly vaporize the analyte, ionizing it in both positive and negative modes [15,31,75,76,104,122,125]. However, the type of matrix and the deposition technique can influence the quality of MALDI spectra. The sample and matrix are usually mixed and dried before being introduced into the vacuum system. After irradiation, the gas-phase ions formed are directed towards the mass spectrometer [39]. MALDI is particularly useful for rapidly detecting peptaibols types from mycelia/conidia, analyzing whole cells, tissues, polymers, and peptides, identifying intact peptides, and determining the full molecular mass of purified peptides. Nevertheless, its limitations in peptaibiotics discovery include the inability to generate peptide fragments and a tendency to display pseudo-molecular ions like [M + H] +, [M + Na] +, [M + K] +, [2M + H] + and [2M + Na] +.Furthermore, the presence of a matrix, aiding ionization, causes substantial chemical noise below m/z ratios of 500 Da, making analysis challenging for samples with low molecular weights [25].

Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time of flight mass spectrometry imaging mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF-IMS) is an emerging approach allowing direct observation of bioactive natural products between two fungi colonies on growth media, expediting the discovery of new bioactive compounds in fungi. Using an ‘intact cell matrix assisted laser desorption/ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry’ (IC-MALDI-TOF-MS) approach, about 15 positively identified species of Trichoderma/Hypocrea are known to produce peptaibiotics, significantly enhancing peptaibiotics screening efficiency [60,74,75]. Analysis and detection of the 20 residue Atroviridins and other new peptaibols from the crude extracts T. atroviride 01 strain, solution conformational analysis of amphiphilic helical and synthetic analogs of the lipopeptaibol trichogin GA IV, and the peptaibols asperelins A and E, Trichotoxins T5D2, 1717A and A-50 E, F and G from T. asperellum TR356 strain, profiling of 11-residue and 14-residue peptaibol from T. virens and paracelsin family of peptaibols from T. citrinoviride were performed by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry [15,63,73,74,121].

1.3.3. Liquid chromatography mass spectroscopy (LC-MS)

Liquid chromatography and tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) represent powerful techniques that offer exceptional capabilities for rapid, cost-effective, and quantitative measurements of organic molecules across various applications. This method combines the physical separation capabilities of liquid chromatography with the mass analysis provided by mass spectrometry. In MS/MS, multiple stages of mass analysis can be performed, often involving molecular fragmentation between these stages [55]. This can be achieved through either multiple mass analyzers separated in space or a single mass analyzer operated differently in time. Instruments such as QTOF, QqQ, and Orbitrap support tandem MS capabilities. The integration of LC with MS enables the determination of the elemental composition and structural elucidation of biological samples [82]. This combination is particularly useful for the efficient, sensitive, and specific detection and analysis of complex mixtures containing hundreds of proteins and peptides at various concentrations [61,64,81]. The sample first undergoes separation by LC and is then sprayed into an atmospheric pressure ion source, converting it into ions in the gas phase. The MS analyzer subsequently sorts the ions based on their molecular mass-to-charge ratio, while the detector counts the ions emerging from the mass analyzer and may amplify the signal generated by each ion. Consequently, a mass spectrum is created (a plot of the ion signal as a function of the mass-to-charge ratio), aiding in the determination of the elemental or isotopic nature of a sample, determining the masses of particles and molecules, and elucidating the chemical structures of the molecules present [53,61]. This technique is highly valuable for detecting and analyzing intricate mixtures containing numerous polypeptides at different concentration levels [60,64,81].

LC/MS utilizes a mobile phase like water, acetonitrile, and methanol with or without formic acid at different concentration for isocratic and gradient eluting of peptides at different time intervals [126]. Thus, an efficient high-resolution LC-MS method is a prerequisite for the purification of microbial polypeptides, which is required for subsequent commercialization of polypeptides as a potential for several application [42,119]. It is best suited for a discovery-based approach when working on unknown peptides, as many peptides are readily amenable to LC/MS analysis. The method relies on the generation of so-called in-source fragments by collision-induced decomposition mass spectrometry (CID-MS) to the skimmer region of an electrospray ionization (ESI) mass spectrometer [44]. Online coupling of LC with MS for the analysis of peptaibols usually includes electrospray ionization and subsequent MS and MS/MS detection. MS full scan spectra can provide information such as the molecular mass of intact peptaibols (derived from [M+H] +, [M-H] −, molecular ions accompanied by typical adduct ions (such as [M+Na] +, [M+NH4] +, [M+K] +, and several charged ions), as well as the charge states of the ions formed by the ion source [101]. The major advantage of using LC/MS is for the selective detection, separation, and characterization of mixtures of peptaibiotics from diverse sources with a high degree of similarity [28,49,54]. ESI and atmospheric-pressure chemical ionization (APCI) are effective ionization techniques used for LC-MS for a wide range of compounds, including high molecular weight, non-volatile, polar, and thermally labile compounds. In addition, it is very advantageous to determine the molecular weights of macromolecules accurately without the operational problems involved in generating a matrix [39]. It is also best suited for a discovery-based approach when working on unknown peptides. The coupling of LC with MS provides the advantages of characterizing retention time of a given peptide including peptaibiotics along with its mass spectral signature, allowing the analysis of complex mixtures of peptaibiotics. It is very sensitive for quantification of peptaibols of very low quantities (5 ng/g) in natural environmental samples. Generally, LC-MS is rapid, cost-effective, and quantitative measurements of peptaibiotics in an enormous variety of applications. However, the soft ionization techniques of electrospray ionization LC-ESI-MS will usually not induce fragments to determine the amino acid sequences of peptaibiotics. In addition, though, ESI-MS methods were improved with the different collision-induced dissociation (CID) techniques such as tandem CID-MS/MS to determine the sequence of amino acids, these methods leave certain positions with isomeric amino acids (e.g., Leu or Ile; Val or Iva) undetermined, therefore the elucidation of the complete sequence requires further examinations [106].

1.4. Diversity and biological activity of Peptaibiotics

The secondary metabolites obtained from various species of Trichoderma have demonstrated numerous biological activities and are commercially employed as bio-protective agents against various diseases. Peptaibiotics, among these bioactive metabolites, have attracted considerable interest due to their diverse biological effects encompassing antibacterial, antifungal, antiviral, antitumor, and neuroleptic properties. Studies have revealed that both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria exhibit sensitivity to these membrane-active compounds, although Gram-positive bacteria tend to be more sensitive than Gram-negative bacteria [10,62]. Peptaibiotics have also exhibited antagonistic effects against phytopathogenic fungi [85]. For example, several disease-causing fungi strains including Lentinula edodes, Flammulina velutipes, Pleurotus ostreatus, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Candida albicans, C. utilis, Cryptococcus neoformans, Penicillium chrysogenum, Aspergillus niger, A. fumigatus, and Trichophyton mentagrophytes were inhibited by Trichopolin I (A) and II (B) peptaibiotics [36]. On the other hand [62], explained the synergism between peptaibols and the inhibition of the membrane-bound β-1, 3-glucan synthase of the host could inhibit the re-synthesis of β-glucans of the host cell wall and sustain the disruptive action of β-glucanases, and all together resulted in an enhanced fungicidal activity. Peptaivirins A and B was the first antiviral peptaibiotics reported against the tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) infection of tobacco plant (Nicotiana tabacum) plant [128]. Studies also highlight the interaction of plants with Trichoderma, indicating that peptaibols from Trichoderma induce plant defense reactions through the salicylate signal pathway, potentially leading to the induction of systemic acquired resistance (SAR) against pathogens and induced systemic resistance (ISR) by the Trichoderma fungi. These compounds affect jasmonate and ethylene response pathways in plants, inducing ISR [20,8]. Furthermore, they induce auxin production and disrupt auxin response gradients in Arabidopsis roots. Alamethicin (ALM) has been demonstrated to induce resistance in plants [35,103]. Additionally, peptaibiotics have been evaluated for their effects on animals, including insect larvae, shrimps, mussels, and mice [19,43,56,93,97]. The amino acid sequences, structural diversity, and biological activities of various peptaibols and lipopeptaibols isolated from different strains of Trichoderma fungi are indicated in the following figures and tables, respectively.

Lxx=Leucine/Isoleucine, Vxx=Valine/Isovaline

| Species/strain | Name of lipopeptaibol | Sequence | Biological activity | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

T. velutinum |

Lipovelutibol A (1) | OcGly Ala Leu Aib Ser Ile Leucinol |

Cytotoxicity |

[108] |

| Lipovelutibol B (2) | OcGly Ala Leu Iva Ser Ile Leucinol | |||

| Lipovelutibol C (3) | OcGly Ala Leu Aib Ala Ile Leucinol | |||

| Lipovelutibol D (4) | OcGly Ala Leu Iva Ala Ile Leucinol | |||

| T. longibrachiatum | Trichogin (A IV/GA IV) | OcAib Gly Leu Aib Gly Leu Aib Gly Ile Leuol | Antibacterial activity | [6] |

| T. koningii | Trikoningins (KBI) | OcAib Gly Val Aib Gly Gly Val Aib Gly Ileol |

Antibacterial activity |

[7] |

| Trikoningins (KBII) | OcIva Gly Val Aib Gly Gly Val Aib Gly Ileol | |||

|

T. polysporum |

Trichopolyns I | OcPro AHMO Ala Aib Aib Ile Ala Aib Aib AMAE |

Cytotoxicity |

[47] |

| Trichopolyns II | OcPro AHMO Ala Aib Aib Val Ala Aib Aib AMAE | |||

| Trichopolyns III | OcPro AHMO Ala Aib Aib Ile Ala Aib Ala AMAE | |||

| Trichopolyns IV | OcPro AHMO Ala Aib Aib Val Ala Aib Ala AMAE | |||

| Trichopolyns V | OcPro AHMO Ala Aib Aib Ile Ala Aib Aib AMAE | |||

| T. viride | Trichodecenins I | OcGly Gly Leu Aib Gly Ile Lol | [37] | |

| Trichodecenins II | OcGly Gly Leu Aib Gly Leu Lol |

2. Conclusion

The Trichoderma genus is recognized for its potential in peptaibiotic production, with a considerable number of these compounds described to date from these fungi. This review primarily focuses on the tools and techniques utilized in screening, purifying, identifying, and assessing the bioactivity of peptaibiotics (peptaibols and lipopeptaibols) derived from various species and strains of Trichoderma fungi. Numerous studies have indicated intensive investigations conducted to explore different peptaibiotics from various Trichoderma fungal strains. The interest in this class of compounds has surged annually due to the advancements in tools and techniques used for their screening and purification, meeting the high demand for these bioactive molecules. Diverse arrays of chromatographic and spectroscopic tools have been employed to study peptaibiotics from Trichoderma fungi. This paper extensively reviews a variety of peptaibiotics (peptaibols and lipopeptaibols), providing details regarding their amino acid sequences and bioactivity characteristics across more than twelve Trichoderma fungi. All these peptaibiotic groups exhibit a wide spectrum of biological activities encompassing antibacterial, antifungal, antiviral effects, as well as cytotoxicity activities like immunosuppressive and neuroleptic properties. Moreover, they have displayed the ability to elicit systemic plant resistance characteristics.