1. Introduction

Increase in population has led to a rise in demand for housing and urban infrastructure in Nigeria (Oramah, 2016). United Cities Local Governments (2010) indicates that in 1995 only 28 cities on the African continent had populations exceeding 1 million and by 2005 this had grown to 43 cities and 59 cities by 2015 (UCLG, 2010). In the region, the urban population of 413 million (40%) in 2010 was expected to rise to 569 million (45%) in 2020. According to the UCLG (2010), in the next 20 years, Africa and Asia will see by far the fastest growth in urban settlements. Not only the 21 mega-cities in 2010 with over 10 million, and 33 with 5–10 million inhabitants, but the world's medium-sized and smaller towns and cities will be responsible for receiving and looking after millions of new urban dwellers (UN, 2010). Homeless people are seen in make-over tents under bridges in urban areas because of inadequate and unaffordable housing and urban infrastructure. According to UNDP (2015), more than half of the world's population now lives in cities and that figure will go to about two-thirds of humanity by the year 2050. In 1990, there were ten “mega-cities” with about 10 million inhabitants or more that were identified indicating an increase in the number of such cities whereas the number of mega-cities increased to 28 in the year 2014 with a population of 453 million people (UNDP, 2015).

It is important to note that despite the advancement of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) in the areas of reducing the percentage of the urban population living in slums worldwide, the absolute numbers continue to grow. Between 1990 and 2010, the proportion of urban dwellers living in slums decreased from 46% to 33% in developed countries, but the total urban slum population in developing regions grew by 26%, from 656 million in 1990 to 827 million in 2010 (UN-Habitat, 2011). According to Jiboye (2011), the growth in urban population will continue to rise, projected to reach almost 5 billion in 2030. Much of this urbanization is predicted to occur in the developing world, with Asia and Africa having the largest urban population. These population increases pose a critical challenge to housing and urban development in Africa. If these challenges are not addressed in a sustainable manner, it can lead to disastrous human problems that can be a threat to the existence of such cities.

The projected population of Nigeria in 2030 has huge implications for the wellbeing of society. A major implication is the inability of the government to meet up with the provision of adequate housing and infrastructure for all, leading to homelessness. According to Global Homelessness Statistics (2018) by the Homeless World Cup Foundation, the number of homeless people is increasing by the day in Nigeria. UNHCR (2007) stated that ‘there are an estimated 24.4 million homeless people in Nigeria as a result of many factors, including rapid urbanization, poverty, and terrorism. The use of sustainable local materials is key to ensuring adequate housing and urban development (UN, 1992)) since the cost of building will come down. According to Ibimilua (2015), there is a need for a realistic housing policy that must consider slum upgrading, periodic repair and maintenance, as well as urban renewal and encouraging the use of local building materials.

There have been many attempts by the Nigerian government to solve the challenges of housing and urban development. These include privatization of the power sector, government civil servant housing scheme, encouragement of private developers, urban water scheme, government housing estates and federal housing schemes (Jiboye, 1997). Other areas of government intervention include the establishment of Federal Housing Authority (FHA), Federal Mortgage Bank of Nigeria (FMBN), Ministry of Housing, Urban Development and Environment and Infrastructure Bank (Kabir, 2004). There have been concerted efforts by the government and its agencies, Building Materials Producers Association of Nigeria (BUMPAN), Real Estate Development Association of Nigeria (REDAN) and other associations in the housing industry to deliver sustainable housing and urban infrastructure in Nigeria over the years. In spite of all these interventions, the housing and urban development sector is still in crisis. There is, therefore, the need to continue to explore ways of ensuring sustainable green cities where housing and infrastructure are available in a sustainable and affordable manner. We believe that research and innovation have a major role to play in this direction.

The aim of this study is to contribute to solving the urban housing and infrastructure problems of Nigeria using research and innovation. First, the evolution of housing and urban development in Nigeria is discussed. Second, the challenges of housing and urban development are identified and discussed. Third, the role of research and innovation in overcoming the challenges is presented. Finally, a sustainable strategy is presented with policy implications. The work is based on an extensive review of existing literature and a critical analysis of the present situation using secondary data.

2. Evolution of housing and urban infrastructure in Nigeria

Urban development is a system of infrastructure (transport, roads, water, power) office, industry, school, hospital, recreation, hospitality and residential housing expansion that creates sustainable cities to enable a large number of people to work and live together in a relatively small area of land sharing facilities (Macomber, 2013). It is achieved by expansion into the underpopulated areas and by the renovation or renewal of dilapidated urban areas. Housing is a building or structure that individuals and their family may live in that meet certain specifications and regulations. According to Agence Française de Développement (2009), the Africapolis team estimates that by 2020, the expected number of settlements in Africa with 10,000 persons or more will reach 574 as against 133 in 1960 and 438 in 2000. This implies that urban growth in Nigeria is not simply a matter of population growth in existing settlements. It also has to do with the emergence of new areas with high urban population densities. These have been encouraged by the creation of States and Local Government Areas over the years. Table 1 shows the population of Nigeria as estimated by NPC in 2016 according to States. In terms of absolute figures, two States (Kano and Lagos) have a population above 10 million. Up to 16 States have a population above 5 million. In terms of population density, 11 States have a population density above 500 persons per square kilometre. Three States (Lagos, Anambra, and Imo) have population densities as high as 900/km2 with Lagos as high as 3000/km2. These figures show that the issues of population dynamics and its pressure on housing and urban development are enormous in Nigeria. This is why a number of policies and programmes have been implemented by different governments over the years with the main aim of providing for affordable housing and infrastructure and minimizing urban and semi-urban slums.

Table 1. Nigeria population by States (2016 Estimated).

| S/No. | State | 2016 Population (Estimated) (Demographic Statistics Bulletin, 2018) | Population Density (No/km2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Abia | 3,727,347 | 590 |

| 2 | Adamawa | 4,248,436 | 115 |

| 3 | Akwa Ibom | 5,482,177 | 774 |

| 4 | Anambra | 5,527,809 | 1141 |

| 5 | Bauchi | 6,537,314 | 143 |

| 6 | Bayelsa | 2,277,961 | 212 |

| 7 | Benue | 5,741,815 | 169 |

| 8 | Borno | 5,860,183 | 83 |

| 9 | Cross River | 3,866,269 | 190 |

| 10 | Delta | 5,663,362 | 320 |

| 11 | Ebonyi | 2,880,383 | 508 |

| 12 | Edo | 4,235,595 | 238 |

| 13 | Ekiti | 3,270,798 | 515 |

| 14 | Enugu | 4,411,119 | 616 |

| 15 | Federal Capital Territory | 3,564,126 | 487 |

| 16 | Gombe | 3,256,962 | 174 |

| 17 | Imo | 5,408,756 | 978 |

| 18 | Jigawa | 5,828,163 | 252 |

| 19 | Kaduna | 8,252,366 | 179 |

| 20 | Kano | 13,076,892 | 650 |

| 21 | Katsina | 7,831,319 | 324 |

| 22 | Kebbi | 4,440,050 | 121 |

| 23 | Kogi | 4,473,490 | 150 |

| 24 | Kwara | 3,192,893 | 87 |

| 25 | Lagos | 12,550,598 | 3752 |

| 26 | Nasarawa | 2,523,395 | 93 |

| 27 | Niger | 5,556,247 | 72 |

| 28 | Ogun | 5,217,716 | 311 |

| 29 | Ondo | 4,671,695 | 301 |

| 30 | Osun | 4,705,589 | 509 |

| 31 | Oyo | 7,840,864 | 639 |

| 32 | Plateau | 4,200,442 | 136 |

| 33 | Rivers | 7,303,924 | 659 |

| 34 | Sokoto | 4,998,090 | 192 |

| 35 | Taraba | 3,066,834 | 56 |

| 36 | Yobe | 3,294,137 | 72 |

| 37 | Zamfara | 4,515,427 | 114 |

Housing and urban development policies and programmes in Nigeria have evolved into various phases which can be categorized into three, namely: the colonial era, post-independence era and post-military era (Morakinyo et al., 2012). Table 2 shows the evolution of the policies and programs in housing and urban infrastructure sector in Nigeria.

Table 2. The evolution of policies and programs.

| S/No. | Description | Year | Status | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Nigerian Building Society | 1956 | Defunct | Ibimilua (2015) |

| 2 | Regional Housing Corporation | 1959 | Defunct | Ibimilua (2015) |

| 3 | National Provident Fund (NPF) | 1961 | Replaced | Jiboye (2011) |

| 4 | National Council on Housing | 1971 | Functional | Ibimilua (2015) |

| 5 | Federal Housing Authority (FHA) | 1973 | Functional | Kabir (2004) |

| 6 | Federal Mortgage Bank of Nigeria (FMBG) | 1977 | Functional | Kabir (2004) |

| 7 | Land Use Decree (LUD) | 1978 | Functional | Otubu (2015) |

| 8 | Nigerian Building and Road Research Institute (NBRRI) | 1978 | Functional | Olotuah and Taiwo (2013) |

| 9 | Infrastructure Development Fund (IDF) | 1985 | Defunct | World Bank (1998) |

| 10 | Federal Housing Authority Act | 1990 | Functional | Jiboye (2011) |

| 11 | 1st National Housing Policy | 1991 | Replaced | Ibimilua (2015) |

| 12 | Urban and Regional Planning Decree | 1992 | Defunct | Ibimilua and Ibitoye (2015) |

| 13 | National Housing Fund | 1992 | Functional | Ibimilua (2015) |

| 14 | Infrastructure Bank Plc | 1992 | Functional | Emoh et al. (2016) |

| 15 | Urban Development Bank of Nigeria | 1992 | Defunct | Kabir (2004) |

| 16 | Nigeria Social Insurance Trust Fund (NSITF) | 1993 | Functional | Abdulazeez (2014) |

| 17 | National Urban Development Policy | 1997 | Defunct | Jiboye (2011) |

| 18 | Nigeria State Urban Development Programme (NSUDP) | 1997 | Defunct | Jiboye (2011) |

| 19 | Housing and Urban Development Policy | 2002 | Functional | Ibimilua (2015) |

| 20 | Abuja Geographic Information Systems (AGIS) and other State GIS | 2003 | Functional | Akingbade et al. (2010) |

| 21 | Federal Ministry of Housing and Urban Development | 2003 | Functional | Jiboye (2011) |

| 22 | 2nd National Housing Policy | 2004 | Replaced | Ocholi et al. (2015) |

| 23 | 3rd National Housing Policy | 2006 | Functional | FRN (2006) |

| 24 | Housing for All under Vision 20:2020 | 2008 | Functional | Onyekakeyah (2008) |

| 25 | Road Map for Housing Development | 2012 | Functional | Agande (2012) |

| 26 | Family Homes Fund (Economic Recovery & Growth Plan: 2017–2020) | 2017 | Functional | World Bank (2018) |

| 27 | Presidential Infrastructure Development Fund (PIDF) | 2018 | Functional | Udo (2018) |

| 28 | Executive Order 7 of 2019 on the Road Infrastructure Development and Refurbishment Investment Tax Credit Scheme | 2019 | Functional | Agbakwuru (2019) |

2.1. Colonial Era (Before, 1960)

The provision of staff quarters for expatriates and other indigenous staff of parastatals and organizations in the public and private sector was the reason for housing and urban infrastructure in the colonial period. The period of colonialism brought about the transformation of the urban system by changing the pattern of distribution of towns in Nigeria (Fourchard, 2013). New towns were created as administrative headquarters, while others emerged as industrial centres. Towns in Nigeria according to regions during the Colonial era are shown in Table 3. The Table shows that there were about 28 towns in Nigeria during the colonial period compared to over 400 urban centres in the current six geopolitical zones in the 36 States of Nigeria (Adamolekun, 2005).

Table 3. Towns in Nigeria according to Regions during the Colonial era (Olujimi, 2015).

| S/No. | Northern Region | Southern Region | Eastern Region |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Kano | Benin | Bonny |

| 2 | Katsina | Ibadan | Enugu |

| 3 | Zaria, Kaduna | Badagry | Abonnema |

| 4 | Sokoto | Lagos | Opobo |

| 5 | Borno (Gazagamo and Kuka) | Wamba | Onitsha |

| 6 | Jos | Abeokuta | Calabar |

| 7 | Kafanchan | Iseyin | Umuahia |

| 8 | Bauchi | Osogbo | Owerri |

2.2. Post-independence Era (1960–1999)

The post-independence period was characterized by some improvements in urban housing and infrastructure provision during the First National Development Plan Period (1962–1968) and the Second National Development Plan Period (1970–1974). The National Council on Housing in 1971 had a plan for constructing about 59,000 housing units nationwide with 15,000 in Lagos and 4000 in each of the other 11 state capitals. But a review of the Second National Development Plan shows only slight improvements in government efforts in housing provision (Ibimilua, 2015). The Civil war (1966–1970) was a period of destruction, especially for the Eastern region. Reconstruction after the civil war started in the Second Development Plan. According to Daily Times (1972), ‘the East Central State Government, despite its natural lean resources, embarked upon the construction of some housing units in Enugu. The East Central State Housing Authority constructed about 104 low and medium-income houses at Riverside Estate, Abakpa-Nike, and Enugu. The housing authority had spent about £300,000 on these buildings by 1972. The buildings were in two categories: a two-bedroom duplex set and a three-bedroom bungalow type’. The third National Development Plan (1975–1980) recorded further improvements in housing programs, policies and delivery in Nigeria. The government accepted housing as its social responsibility and played a key role in the housing sector by involving itself directly in the provision of housing, instead of shifting the responsibility to the private sector alone. During this period, the Nigerian Building Society was renamed Federal Mortgage Bank of Nigeria with the promulgation of Decree No 7 of 1977 which also brought some improvements into housing delivery in Nigeria. The enactment of the Land Use Decree (LUD) of 1978 solved the problem of dual land tenure structure by granting access to land to all Nigerians through the State governments. The LUD came to stabilize the ownership and acquisition of land. Moreover, the importance of local building materials, as well as the relevance of labour and construction industry during the post-independence era were focused on by the constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria (1979). In this same year, the Employees Housing Scheme Decree No 54 of 1979 was promulgated (Ibimilua, 2015). This decree made provision for staff housing and housing estates possible. The Fourth National Development (1981–1985) witnessed a housing provision drive based on the concept of affordability and citizenship participation. Consequently, the government embarked on an ambitious Shagari Housing programme which involved the construction of 160,000 housing units nationwide between 1979 and 1983 at its first phase (Irouke et al., 2017). The programme was based on the concept of affordability and citizen participation. However, the success of the programme was below average as only about 20% of the set target was achieved.

The housing policy in the 1980s and 1990s led to the neglect of rural areas while the housing infrastructures in the urban areas were improved. This era was characterized by a high rate of urbanization leading to a housing shortage in urban centres. The Mortgage Institutions Decree No 53 of 1989 was enacted during the military era resulting in improvements in housing policies and delivery. The goal of the policy was to ensure that Nigerians own or have access to decent, safe and healthy housing and accommodation at an affordable cost. The Babangida's administration developed the Economic Liberalization Policy which supported the participation of private organizations in housing delivery. The promulgation of the Urban and Regional Planning Decree 88 of 1992 and the National Housing Fund (NHF) Decree No 3 of 1992 was in the era (Ibimilua, 2011). The NHF was entrusted with the responsibility of ensuring the continuous flow of fund for housing construction and delivery in Nigeria.

The post-independence era saw the subsequent creation of 12 States in 1966; 19 States in 1976; 21 States in 1987; 30 States in 1991 and 36 States in 1996 out of the four existing regions. The Federal Capital Territory (Abuja) was created in 1976 but officially became Nigeria's capital on 12 December 1991. Development in the areas of construction of roads, power, railways, bridges, airports and housing estates followed these political developments. Each of the 36 State governments and FCT administration embarked on State Capital development programmes through State Capital Development Authorities. Each of the States established investment development companies and estate developments. New towns were delineated. Various institutions of higher learning and research institutions were established during this period. At the national level, an expressway was constructed from Lagos to Ibadan (Gabriel, 2014). The Carter Bridge which was originally constructed prior to Nigerian independence by the British colonial government was deconstructed after independence and redesigned and rebuilt during the late 1970s. The Alaka-Ijora flyover, on the Iddo end of the span, was completed in 1973 (The Daily Trust, 2013). There were changes in the taste of housing types resulting in a shift from mud and thatched houses to a cement block and corrugated roofing houses. Establishment of wastewater treatment plants and pipe-borne water supply were carried out in all the new States capital cities.

2.3. Post – Military Era (1999–2018)

The policy of ‘housing for all in the year 2000’ was formulated before the millennium. This policy was not realized by the year 2000 due to administrative bottlenecks, though it was rigorously pursued. Notwithstanding, the Housing and Urban Development Policy was formulated in the year 2002. The policy was developed to solve the issues of the Land Use Act as well as to allow land banking and ownership to operate in a free market economy. The post-military era (1999–2019) has witnessed marginal improvement in the Nigerian housing situation. However, the Federal Government policy on monetization and privatization (1999) appear to have slowed down public support for housing in Nigeria. Informal settlements started to emerge due to demographic pressures, increased housing and population density and the inability of cities to properly house newcomers. These, notably on the periphery of cities, have become the representation of the urbanization of poverty (Gandy, 2005). These new urban areas are plagued with a shortage of services and infrastructure. The emergence of urban slums is also prevalent within city limits. Such slums are characterized by an unacceptable high population densities shortage of urban infrastructure and housing.

The inability and failure of the policy to adequately resolve the backlog of housing problems in the country made the civilian government of President Obasanjo review the 1991 National Housing Policy in 2006. The target of the new policy was to remove the drawbacks to the realization of housing goal of the nation. The Seven-Point Agenda of the Yar’Adua Administration of 2007 attempted to address the housing and infrastructural deficit in Nigeria by engaging in the provision of critical infrastructure and reviewing the Land use laws to facilitate the proper use of the Nation's land assets for socio-economic development; and citizens' access to mortgage facilities (Dode, 2010). President Goodluck Jonathan in 2012 pushed for the revolution of the sector by translating the National Housing Policy and National Urban Development Policy into a Road Map for Housing Development (Agande (2012). The road map was to address the challenges of achieving a housing revolution in the country, within the shortest possible time and also provide the pathway for transforming our cities into livable and functional human settlements. A new government came into being at the Federal level in 2015 under President Muhammadu Buhari. The major economic blueprint of the administration is the National Economic Recovery and Growth Plan (NERGP). The plan identified six important sectors for development. One of the sectors is Construction and real estate. The plan is to have a social housing programme called Family Homes Fund under Public-Private Partnership (PPP) arrangement to provide funding of up to one trillion Naira for housing in Nigeria. The project is to provide access to funds, train artisans, construct 2, 700 housing units, reposition the Federal Mortgage Bank and construct 12 Federal Secretariat Complexes in the States. The plan also addresses infrastructure projects including Mambilla hydropower plants, airports, coastal and inland railway, and Abuja Mass Transit rail line. It is too early to assess the success of these programmes but they are good plans that can impact on the housing and urban infrastructure positively. Although a lot has been done in housing and urban development over the years, the situation is that there are deficits. Many cities in Nigeria do not have enough housing for residents. Even what is available is not affordable. Most of the cities have divided towns where some neighbourhoods have low population density with good housing and infrastructure while others are slums. Urban infrastructure is currently in disarray.

3. Obstacles to housing and urban development in Nigeria

The challenges of housing and urban development in Nigeria have been discussed by different researchers. These include: poor maintenance of infrastructure, bribery and corruption, lack of product-driven research, preference of foreign goods and services over local ones, poor policy formulation and implementation, high cost of building materials, poor compliance to regulations and standards, poor budgeting and budget implementation, lack of commercialization of research findings, poor funding mechanism and lack of skilled manpower (Ibimilua, 2015).

3.1. Poor maintenance of infrastructure

Nigeria is ravaged by lack of maintenance culture in public projects and infrastructure (Haruna, 2009; Uma et al., 2014; Tijani et al., 2016). This has resulted in the presence of a high number of dilapidated housing and urban infrastructure which increases the housing and urban infrastructure deficit in Nigeria. Poor maintenance of housing and urban infrastructure affects the performance of the infrastructure and can lead to outright damage or failure. Maintenance culture which encompasses provision for adequate care of infrastructure has not been given the desired attention by resource managers in Nigeria over the years (Uma et al., 2014). Nigeria has about 195,500 km of road network all over the country. Out of the whole, a proportion of about 32,000 km is federal roads while 31,000 km are state roads. A large proportion of these roads is in poor condition due to lack of maintenance (FRN, 2000). Tijani et al. (2016) opined that most of our public and private facilities are in a total state of a mess because of the non-existence of maintenance policy, or poor implementation of the policy. A good example is the Urban Mass Transit buses introduced in Abuja the administration of President Obasanjo (1999–2007) which are today dilapidated.

3.2. Bribery and corruption

Ogundiya (2009) in his work saw corruption as the exploitation of public position, resources and power for private gain. Despite huge allocations of money to the housing sector in the National Development Plans, very little was achieved in terms of meeting specified targets in housing construction (Gandy, 2005). Mismanagement of project funds has led to the presence of many uncompleted projects in Nigeria (Adeyemo and Amade, 2016). According to Crowe (2011), political corruption in Nigeria has led to a concentration of wealth among few elite government officials resulting in a poor level of infrastructural development in Nigeria. Report by National Bureau of Statistics (2017) pointed out that the fact that almost one-third of Nigerians who had contact with a public official paid one or more bribes over the course of the year shows that bribery is clearly a significant issue in the lives of Nigerians. Despite the concerted efforts by the Economic and Financial Crime Commission (EFCC), Independent Corrupt Practices and Other Related Offenses Commission (ICPC), Nigerian Police, DSS and other government security agencies, the negative narrative about corruption has not changed significantly. The implication of this is that well thought out policies and programmes in the sector are poorly executed.

3.3. Land disputes and speculation

One of the major causes of conflict in Nigeria is land disputes. The issue of land grabbing has altered the urban cities plans leading to land disputes that have claimed so many lives and properties. Blench (2003) pointed out that Fulani pastoralists and farmer crisis represent “the most significant focus of herder/farmer conflict in Nigeria. Research by Abegunde (2011) identified the need for the Nigerian's policy Makers to review the existing land use laws at both local and regional levels in Nigeria. This is because the general land use laws could not be effectively applied to the different parts of the country. Each part of the country have their peculiar issues with respect to land disputes. These issues ranges from land grabbing in the southern part of Nigeria to herders-farmers crisis which peculiar to the northern part of the Nigeria. As Nigeria's population kept growing every year (UCLG, 2010), this crisis will definitely be getting worse if serious steps are not taking to ensure effective distribution of land and its resources to the populace. Otubu (2015) advocated for the review of the Land Use Act and land ownership in Nigeria. The review of the Land Use Act will help to address the issues associated with the implementation of the Act which will eliminate some of the land crisis in Nigeria.

3.4. Preference of foreign goods and services to local ones

There has been neglect of the use of local goods and services by operators in the housing sector. This could be as a result of poor standards, lack of promotion of the use of local goods and services by government and lack of patriotism by citizens. The rate of importation of goods and services in the housing and urban development sector in Nigeria is alarming. According to Abolo (2017), imported raw materials are cheaper and considered more appealing despite their poor quality and safety issues sometimes. This is seen in the way the government prefers to engage foreign firms in big infrastructure probably because of loan-funded arrangements. Hence, the local Engineers and Specialists in housing and urban development sector are left with minor projects. This unfair competition with foreign goods and services results in poor patronage of local goods and services in the housing and urban development sector in Nigeria (Ofili, 2014). In most building materials markets in Nigeria, over 80% of goods (plumbing, wiring, tools, equipment, steel, etc.) are imported. It is only in cement and granite that significant progress has been achieved in local content.

3.5. Poor policy formulation and implementation

In 1991, the National Housing Policy was enacted in order to propose possible solutions to housing problems in Nigeria (Arimah, 1999). At inception, the basic goal of the policy was to provide affordable housing to accommodate Nigerian households in a livable environment. However, twenty-seven years after the promulgation of the policy and eighteen years after the target year 2000, many Nigerians are still unable to own a house while several others are living in indecent houses.

The Nigerian housing policy was well conceived with the fundamental elements of feasibility, affordability and limited time frame required for the completion of the programs. To some extent, the various policies and programs of housing in Nigeria have been able to make significant improvements in housing production and delivery. The guidelines for housing construction, maintenance and delivery are stipulated by the housing policies. Nevertheless, the policies and programs are besieged by shortcomings such as poverty, ever-increasing costs of construction and building materials, homelessness, weak institutional frameworks for housing delivery, administrative bottlenecks in plan approval and collection of certificates of occupancy, program monitoring as well as review (Jiboye, 2011). The gap between policy formulation and policy implementation must be bridged in order to achieve the desired development in the sector. This can be achieved through more effective implementation, monitoring and evaluation strategy. Government agencies such as Federal Housing Authority (FHA), State Housing Development Authority, National Office for Technology Acquisition and Promotion (NOTAP), Federal Ministry of Works and Housing (FMWH), State Ministry of Works and Housing (SMWH), National Assembly Committee on Housing (NACH) and State Assembly Committee on Housing (SACH) will be instrumental in achieving policy formulation and implementation.

3.6. High cost of building materials

It is becoming increasingly difficult for an individual to own a house as a result of the high cost of building materials in Nigeria. This is because building material is a major component of construction cost and a reduction in the cost of material will result in the reduction in the overall construction cost. According to Babatunde (2008), the average earning the power of a middle-class Nigerian is in the range of 75,000–100,000 Naira per month whereas the cost of owning a house in Nigeria runs into several millions of Naira. Reliance on expensive conventional building materials has escalated the cost of housing and other infrastructure. A shift towards the use of alternative and local building materials will definitely bring down the cost of materials and affordable housing will be possible. Alternative and local building materials are cheaper but seldom used because of poor efficiency in terms of strength and durability. The inability of improving the strength and durability of the alternative building materials in order to make them more appealing to Nigerians has kept the price of the conventional building materials very high.

3.7. Poor compliance to regulations and standards

Professional bodies such as Nigerian Institution of Civil Engineers (NICE), Nigerian Institute of Architects and Nigerian Institute of Building (NIOB) are entrusted with the task of developing standards for the regulation of building and urban infrastructures whereas Council of Registered Builders of Nigeria (CORBON) and Council for the Regulation of Engineering in Nigeria (COREN) and Federal/State Ministry of Works and Housing are mandated to enforce the codes and standard of building and urban infrastructure. The Standard Organization of Nigeria (SON) and the Nigerian Society of Engineers (NSE) are also empowered to enforce engineering codes and standards among practitioners across the country (Anyaeji, 2017). The ineffectiveness of the regulatory bodies to ensure strict adherence to regulation and standards in housing and urban development sector has affected the sector adversely. The rate of building collapse in Nigeria is alarming (Table 4).

Table 4. Building collapse in Nigeria (Fagbenle and Oluwunmi, 2010), (Nnabugwu, 2012), (Ejembi, 2016), (Olawoyin, 2017), (Babalola, 2019), (Olukoya, 2019).

| S/N | Description | Date of Collapse | S/N | Description | Date of Collapse |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ita Faji, Lagos Island | March 2019 | 42 | Angwan Dosa, Kaduna State | December 2013 |

| 2 | Sogoye area, Ibadan | March 2019 | 43 | Gwarimpa, Abuja | January 2012 |

| 3 | Apo Mechanic Village, Abuja | December 2018 | 44 | Freeman Street, Oyingbo, Lagos State | July 2012 |

| 4 | Port Harcourt, Rivers State | November 2018 | 45 | Apo Mechanic village, Abuja | August 2012 |

| 5 | Benue State University Makurdi, Benue State | November 2018 | 46 | Anikantamo Street, Adeniji-Adele, Lagos State | August 2012 |

| 6 | Otolo Nnewi, Anambra State | October 2018 | 47 | Dutse-Alhaji, Abuja | August 2012 |

| 7 | Zaria, Kaduna State | September 2018 | 48 | Jakande Estate, Isolo, Lagos State | November 2012 |

| 8 | Jabi, Abuja | August 2018 | 49 | Idumota/Ebute Ero, Lagos State | July 2011 |

| 9 | Opi, Enugu State | June 2018 | 50 | Mararaba, Abuja | July 2011 |

| 10 | Agege, Lagos State | March 2018 | 51 | Mpape, Abuja | August 2011 |

| 11 | Ibadan, Oyo State | March 2017 | 52 | Maryland, Lagos State | October 2011 |

| 12 | Ogidi, Anambra State | March 2017 | 53 | Cairo Market, Oshodi, Lagos State | May 2010 |

| 13 | Unguwar Tambai, Maigatari, Jigawa State | April 2017 | 54 | Ikole Street, Abuja | August 2010 |

| 14 | Ilasa area, Lagos State | May 2017 | 55 | Gimbiya Street, Garki, Abuja | August 2010 |

| 15 | Obi/Akpor, River State | May 2017 | 56 | Victoria Island, Lagos State | September 2010 |

| 16 | Massey Street, Lagos Island, Lagos State | July 2017 | 57 | Ogbomosho, Oyo State | February 2009 |

| 17 | Umuguma, Owerri, Imo State | July 2017 | 58 | GRA, Enugu | August 2009 |

| 18 | Ojo area, Lagos State | August 2017 | 59 | Ibadan, Oyo State | March 2008 |

| 19 | OniFufu Compound, Ogun State | March 2016 | 60 | Ojota, Lagos State | April 2008 |

| 20 | Lekki District, Lagos State | March 2016 | 61 | Wuse, Abuja | August 2008 |

| 21 | Itokun Market, Ogun State | May 2016 | 62 | Farm Center Layout, Kano State | August 2008 |

| 22 | Ndiagu-Ogidi, Anambra State | July 2016 | 63 | Egerton Street, Oke-Arin, Lagos State | June 2007 |

| 23 | Obosi and Oko, Anambra State | July 2016 | 64 | Ebute-Metta, Lagos State | June 2007 |

| 24 | Asaba, Delta State | July 2016 | 65 | Ajeromi Ifelodun, Lagos State | January 2006 |

| 25 | Uratta village, Imo State | August 2016 | 66 | Broad Street, Lagos Island, Lagos State | March 2006 |

| 26 | Kano State University, Kano State | August 2016 | 67 | Ikpoba-Okha, Edo State | April 2006 |

| 27 | Gwarimpa, Abuja | August 2016 | 68 | FCT, Abuja | June 2006 |

| 28 | Kado Village, Abuja | October 2016 | 69 | Ebute Metta, Lagos State | July 2006 |

| 29 | Uyo, Akwa-Ibom State | December 2016 | 70 | GRA, Port Harcourt, Rivers State | July 2005 |

| 30 | Yaba area, Lagos State | July 2015 | 71 | Mushin, Lagos State | April 2001 |

| 31 | Bukuru, Jos, Plateau State | September 2015 | 72 | Iju-Ijesa, Lagos State | August 1999 |

| 32 | Swamp Street, Odunfa, Lagos Island, Lagos State | October 2015 | 73 | Ifo, Ogun State | October 1999 |

| 33 | Ibadan, Oyo State | May 2014 | 74 | Akure, Ondo State | October 1998 |

| 34 | Ikotun Egbe, Lagos State | September 2014 | 75 | Abeokuta, Ogun State | November 1998 |

| 35 | Bukuru, Jos, Plateau State | September 2014 | 76 | Mushin, Lagos State | June 1997 |

| 36 | Umuahia, Abia State | May 2013 | 77 | Oshodi, Lagos State | May 1996 |

| 37 | Ibadan, Oyo State | July 2013 | 78 | Ogba, Lagos State | October 1995 |

| 38 | Ebute Meta, Lagos State | July 2013 | 79 | Port Harcourt, Rivers State | June 1990 |

| 39 | Hadeja Road, Kaduna State | July 2013 | 80 | Barnawa Housing Estate, Kaduna | August. 1977 |

| 40 | Lagos Island, Lagos State | September 2013 | 81 | Mokola, Ibadan, Oyo State | October 1974 |

| 41 | Muri Okunola Street, Lagos State | November 2013 |

3.8. Poor funding mechanism

Access to finance is a serious challenge for Nigeria economic sector. Lack of access to finance affects the supply of housing and urban infrastructures in Nigeria. Ogunwusi and Ibrahim (2014) remarked that one of the major problems limiting the contribution of research and innovation to national development in Nigeria is the low level of fund available for research and innovation activities. Although there is a reasonable supply of housing credit by financial institutions, there is limited access to finance by low-income households. Okonkwo (1999) advocated that the Federal Mortgage Bank of Nigeria should be given adequate resources by the government to strengthen its financial and operational capabilities. Housing and urban infrastructure funding mechanism in Nigeria includes Federal Mortgage Bank of Nigeria (FMBN), Commercial Mortgage Banks, Micro Finance Banks (MFB), National Housing Fund (NHF), Infrastructure Banks Plc (IB Plc), Lapo Micro Finance Bank (Lapo MFB), Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN), Nigeria Mortgage Refinance Company (NMRC) and Private Developers. Despite the available funding mechanism in Nigerian housing and urban infrastructural sector, the desired result of housing for all has not been achieved because of the high-interest rate of housing loans and administrative bottlenecks in getting a housing loan.

3.9. Lack of skilled manpower

The skilled manpower required in the building and infrastructure industry include artisans, electricians, tilers, carpenters, plumbers, welders, painters, etc. Inadequate availability of skilled manpower has affected the provision of adequate housing and urban infrastructure in Nigeria (Onwualu, 2017). The managing director of Bank of Industry, Mr Olukayode Pitan, bemoaned that the stock of competent skilled construction workers is rapidly decreasing, with a 15 per cent annual decline of artisans in the construction sector (Ibrahim, 2018). Poor quality work leading to high maintenance cost and project failures has besieged the nation as a result of a deficit in skilled manpower. Establishment of functional training Institutions by the government and private sector for artisans and other skilled personnel in the field of housing and urban development will go a long way in providing adequate skilled manpower. Certification, retraining and continuous personal development courses important. Closely related to skills is a lack of tools and machines for the construction industry.

3.10. Poor budgeting and budget implementation

In Nigeria, research and innovation are mainly funded by the government with a meagre budget of 0.1% of GDP (Gross Domestic Product) instead of at least 1% of GDP as stipulated by United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). The infrastructural need of the Nigerian society keeps increasing as the population of the nation keeps increasing. There is a huge gap between the infrastructural need an annual budget allocation in Nigeria. Late passage of the annual budget in Nigeria has led to poor implementation of the budget and sometimes the budget release is about 50% or less. Ojoye (2018) recommended that the government must ensure adequate funds are not only allocated to capital expenditure but also disbursed timely and utilized as budgeted. Hence, there is a need for the Nigerian government to increase its budgetary allocation to infrastructural development in order to bridge the gap in infrastructure. The idea of government estates was discontinued in 1999. This needs to be revisited as private estates are expensive.

3.11. Lack of product-driven research

Research on building and infrastructure development are currently going on in Universities, Polytechnics, Nigerian Building and Road Research Institute (NBRRI) and Federal Ministry of Works and Housing (Jiboye, 2011). The Obasanjo Housing Estate, Ado-Ekiti, Nigeria was constructed with local building materials (red bricks) using NBRRI fabricated interlocking block-making machine. The use of earth materials for building in Nigeria has arisen out of extensive applied research and development notably by the NBRRI (Olutuah and Taiwo, 2013). The problem with the research institutions is that there are no adequate linkages with industry (Kemmis, 2008). Lack of linkages between research institutions and industries is as a result of lack of product-driven research. National Board for Technology Incubation (NBTI) provides institutional infrastructure and mechanism for the development and commercialization of research and development (R&D) outputs and inventions. Research ventures are expected to end in products that could be commercialized to add value to society. This is not the case of most research works in Nigeria. Most of the research findings in Africa end up on the shelves in the library (Nsa, 2003). The lack of interaction among elements of the innovation system, weakness in R&D activities and marketing plan, poor or no incentives from the government to drive the industry to utilize local technology or research results have led to poor commercialization of research findings (Ugonna and Onwualu, 2016). There is a lack of product-driven research that will drive the development of housing and urban infrastructure in Nigeria. These research are required in the areas of building materials, methods of construction, housing delivery systems, financial products, maintenance, etc.

3.12. Lack of commercialization of research findings

In Nigeria, the issue of research commercialization is not receiving the desired attention (Onwualu, 2014). Ogunwusi and Ibrahim (2014) noted that ‘effective commercialization of research results in any nation will depend on rapid technological innovation, effective strategic management of knowledge and a clear focus on value-added goods, services and industries. This is not yet happening in Nigeria as a result of inadequate supports and poor funding of research by institutions, government and private sector. The Nigerian government is yet to fully support research works like its counterpart in developed countries. National Board for Technology Incubation (NBTI) and National Office for Technology Acquisition and Promotion (NOTAP) have the responsibility of managing the intellectual property rights and technology transfer issues in Nigeria and hence facilitates the process of commercialization (Ukpai, 2009). Less than 2% of Research & Development (R&D) in Nigeria have been commercialized. This led Siyanbola et al. (2012) to recommend a change in commercialization strategy in Nigeria through networking and collaboration among key stakeholders in the commercialization process. Onwualu (2006) identified the steps and actions required for taking a project from initiation to commercialization which includes idea generation, screening of ideas, research and development, business analysis, prototypes development, test marketing and commercialization. A framework for commercialization was presented Ugonna and Onwualu (2016).

4. The role of research and innovation in overcoming the obstacles in housing and urban development in Nigeria

The obstacles identified above can be eliminated through research and innovation. These include the formulation of good policies, development of new materials, the improvement on the efficiency of local materials, job creation, better understanding of population dynamics, evolution of the integrated approach to housing and urban development, and new functional designs for housing and urban infrastructure.

4.1. Formulation of good policies and their implementation

The outcome of research in the housing and urban development sector can be harnessed and used by policymakers in the formulation of good policies that will help in the advancement of housing and urban development sector in Nigeria. Hence, creating a database for the storage of research findings will make it easy for policymakers to easily access the research findings and utilize them in formulating well-informed policies for sustainable housing and urban development. According to Lawal (1997), a most comprehensive housing policy should address the role of government which may vary from the planning and control of all aspects of housing production – land, investment, construction and occupancy – to intervention only at certain levels or when solutions are needed for specific problems involving such matters as land use plans and controls, credit and financial aids, subsidies to low income groups, rent control, slum clearance and relocation. There is also a need for an innovation policy framework that will produce researchers with entrepreneurship skills. Therefore, a major role of research and innovation can play in this area include a comprehensive study of the policies, development of new policies, the study of the implementation of existing and past policies, and study of best global practices.

4.2. Development of new building materials

Product-driven research will surely give birth to new building materials that can be commercialized. When new materials are produced via research, they will compete with the conventional materials and will help to check the hike in the prices of the conventional materials (Kwon-Ndung et al., 2014). This type of competition will result in the availability of affordable and sustainable materials for housing and urban development. Both government and private-owned manufacturing firms should support productive research and innovation to develop new products and processes that would enhance competitiveness. New frontiers in building materials research include: nanotechnology, natural fibre reinforcement, use of agro-wastes in making bricks, thermal envelop materials, composite, materials with acoustics, energy-efficient construction, lightweight materials, smart materials, green building, biocomposites, modelling of materials, nanocomposite materials, hybrid materials, green pave and advanced materials.

4.3. Improvement in the efficiency of local building materials

The use of research to make local building materials better is important in overcoming the challenges of housing and urban development in Nigeria. Applying research findings aimed at improving the strength, durability and efficiency of local materials will enable them to compete favourably with foreign ones. Oni (2009) pointed out that it will be difficult to produce affordable housing without making use of locally sourced materials obtained through research and innovation. Research and innovation tasks in this area include making materials serve longer terms as well as withstand extreme weather conditions. This can be achieved by improving the strength and durability of local building materials. Recent work on the use of agro-waste ash to improve the strength of earth-based building materials has uncovered the potential of using this locally sourced materials for the provision of affordable housings (Obianyo et al., 2021). Obianyo et al. (2020a) studied on achieving time and energy efficiency of local building materials by using multivariate predictive models for the successful prediction of the compressive strength of agro-waste stabilized lateritic soil. The use of bone ash for stabilization of lateritic soil for building application has been explored by Obianyo et al. (2020b). The use of agro-waste ash for improving the efficiency of local building materials will not only increase the strength of the materials but will also add economic value to the agro-wastes. Thus, ensuring sustainability by using the ashes from agro-waste to make the local building materials perform better.

4.4. Job creation

Research is like a business. Research leads to innovation which leads to new material and new method of construction through start-ups and clusters. The commercialization of research findings creates many entrepreneurs. These entrepreneurs can come together as clusters to establish cottage industries with the aim of solving the needs of society while making money. There is a need for key institutions that are responsible for linking knowledge to innovative entrepreneurship and growth to step up their game to see that the wealth of knowledge emanating from research findings are turned to useful products (Sanandaji, 2011). They should also assist in overcoming the challenges of providing an institutional framework that connects knowledge and entrepreneurship in promoting housing and urban development in Nigeria. A good example is the promotion of technology-based start-ups in the building industry. These start-ups can focus on service delivery, connecting professionals and businesses in the industry and providing cost-effective linkages to consumers.

4.5. Better understanding of population dynamics

The continuous population increase in Nigeria demands a better understanding of population dynamics in order to cope with the challenges associated with population growth. Uncontrolled population growth has huge implications such as inadequate power supply, poor waste disposal, inadequate housing, and growth of slums, traffic congestion, and shortage of water (Aluko, 2010). The role of research in providing a better understanding of the population dynamics and infrastructural development is key to developing a functional housing policy for the provision of housing and urban infrastructure. Research focus in this area includes the study of rural-urban migration, settlement of indigenes population, housing needs and requirements, as well as the socio-economic status of consumers in the housing sector.

4.6. Evolution of integrated approach to housing and urban development

Nigeria must begin to add action to the talk regarding her infrastructural development to prevent the country from experiencing a serious crisis in the near future. Ojoye (2018) noted that “with a population expected to hit 397 million by 2050, Nigeria's infrastructure will come under serious pressure, which can hinder economic development and deny citizens of the much-desired national prosperity except if something drastic is done”. Therefore, there is a need for a more functional integrated approach to housing and urban development to forestall the imminent crisis in housing and urban infrastructural sector. The integrated approach of Public-Private Partnership (PPP) is key to achieving the desired infrastructural development in Nigeria. According to Ugonabo and Emoh (2013), PPP basically involves the provision of land by the government to interested private developers who are able and willing to utilize their resources to develop real estate for sale to members of the public including institutions. Nigeria government at all levels can partner with the private sector to provide affordable infrastructure to Nigerians. Good models of PPP can be obtained through research. Research focus in this area includes the study of successful PPP schemes in other countries, the study of the existing PPP projects in the sector in Nigeria and evolving new PPP models to suit the Nigerian environment.

4.7. New functional designs for housing and urban infrastructure

The government has been unsuccessful in its approach to achieving the goal of the National Housing Policy and its institutional framework. Therefore, incisive research to develop new functional designs for housing and urban infrastructure is a necessity for providing affordable housing and urban infrastructure in Nigeria. A comprehensive housing and urban infrastructural need assessment based on reliable data obtained via research especially of demographic parameters such as population growth and urbanization trends have to be thoroughly done (Olutuah, 2015). These assessments will be very instrumental in developing new functional designs and policies for the desired development in the housing and urban infrastructural sector. This can be done on a regional basis which can lead to regional housing and infrastructure development plans.

5. Policy imperatives

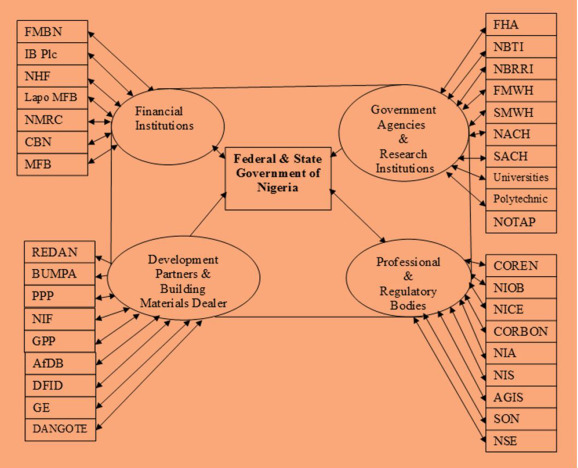

The policy imperative of this study indicates the need for the application of research and innovation in overcoming the obstacles to sustainable housing and urban development in Nigeria through modification of existing policies to take into consideration issues raised in this study. The study shows that such policies will focus on the use of PPP to establish and operate satellite towns, condominiums, housing schemes and urban infrastructure including transport, security, waste management, power, and water. For this to work, there is a need to ensure that a functional and responsive institutional framework is in place. Currently, the institutional framework for the development of housing and urban infrastructure in Nigeria is as shown in Fig. 1. There is a need to strengthen the operations of these institutions through more effective legislation, policy implementation and research.

Fig. 1

Fig. 1