Introduction

The delivery of nucleic acids, small RNAs and oligonucleotides to induce production of a therapeutic protein, silence a gene or generate protective immunity against a pathogen can be accomplished using viral, physical or non-viral means. Non-viral gene delivery via nanoparticulates (NPs) and complexes, composed of nucleic acids combined with cationic-polymers or lipids, offer improved safety profiles, are conducive to cost-effective large-scale production, possess a greater capacity for delivering large nucleic acids and have additional design flexibility (e.g. complexing material, targeting moieties, controlled release), compared to viral vectors. Unfortunately, non-viral systems typically suffer from reduced transfection efficiency compared to viral delivery systems [1]. Nevertheless, many advancements in non-viral gene delivery systems have occurred, and such progress is reflected by the recent increase in non-viral, NP-based gene therapies entering various stages of clinical trials (see Ref. [1] for complete list).

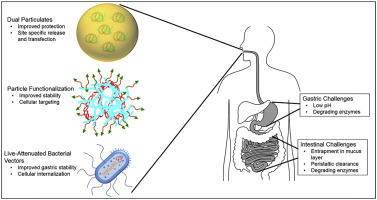

The majority of non-viral systems entering clinical trials are administered via intravenous, intramuscular, intraperitoneal or subcutaneous injections [1]. Although these modes of delivery are effective, many require administration by trained medical staff, are invasive in nature and can lead to undesired off target effects due to systemic administration. In contrast, oral delivery represents an exciting alternative strategy that can promote patient compliance, as well as improve ease of administration. In addition, oral delivery allows for access to a large cellular surface area (i.e. intestinal epithelium) for transfection, and the ability to elicit local and systemic responses (e.g. mucosal and systemic immune responses in the case of DNA vaccination) 2, 3. However, non-viral gene delivery via the oral route poses unique design challenges for researchers (See Figure 1). Oral delivery systems must be designed to overcome the variable conditions encountered along the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, including variations in pH that range from 1 in the stomach to 7 in the small intestine and colon, and an abundance of enzymes (e.g. pepsin in the stomach and trypsin, lipases, amylases, and proteases in the intestine) [4]. The intestinal mucus layer, which consists of hydrated mucin fibers that form a physical barrier up to 450 μm thick, and periodic turnover of the mucus layer (usually 4–6 h), present additional obstacles for orally delivered therapeutics [4]. Therefore, to ensure that delivery vehicles endure the GI environment, careful material selection and system design is crucial for successful oral gene delivery.

Figure 1. Extracellular and intracellular barriers associated with oral nonviral DNA delivery for gene therapy and DNA vaccination applications. The gastrointestinal tract represents a unique and challenging administration routefor nonviral DNA delivery systems. For successful expression of the desired gene in the intestine, nonviral vectors must overcome a wide range of extracellular A) and intracellular B) barriers. Upon oral administration, nonviral vectors are first introduced to the gastric environment, where they are subjected to gastric juices that range in pH from 1.5 to 3.5. In addition, chief cells in the gastric mucosa secrete pepsinogen that is activated in acidic pH to pepsin and is responsible for digesting proteins and nucleic acids. Nonviral vectors must remain stable and avoid dissolution during gastric emptying, which can reach up to 120 min, depending on various conditions, including fasted or fed state. Upon gastric emptying, nonviral vectors are then introduced to the intestinal environment and a subsequent change in pH of up to 7. The intestinal lumencontains numerous enzymes, including trypsin and nucleases, making the intestine the main site of nucleic acid degradation. In the intestine, nonviral vectors must also overcome numerous physical barriers including the intestinal mucus layer, which serves to trap and remove foreign particles through normal peristaltic turnover. Upon overcoming extracellular barriers, nonviral vectors must also overcome intracellular barriers to achieve transgene expression for both gene therapy and DNA vaccination (B). For both gene therapy and DNA vaccination, nonviral vectors must first be internalized (1.), typically through various endocytic pathways that result in vector internalization into endosomes. The vector must then escape the endosome prior to endosomal acidification, and once in the cytoplasm the nucleic acid needs to dissociate from the carrier and traffic to the nucleus (2.). Finally, the nucleic acid must be internalized into the nucleus for transcription to mRNA and translation to the desired protein (3.). For gene therapy applications, additional barriers include adequate expression of the transgene to achieve a therapeutic effect. For DNA vaccination applications, targeting nonviral vectors to professional antigen presenting cells (APCs), is considered the most promising strategy. Targeting APCs introduces additional challenges, as APCs such as dendritic cells are particularly difficult to transfect.

Figure 1. Extracellular and intracellular barriers associated with oral nonviral DNA delivery for gene therapy and DNA vaccination applications. The gastrointestinal tract represents a unique and challenging administration routefor nonviral DNA delivery systems. For successful expression of the desired gene in the intestine, nonviral vectors must overcome a wide range of extracellular A) and intracellular B) barriers. Upon oral administration, nonviral vectors are first introduced to the gastric environment, where they are subjected to gastric juices that range in pH from 1.5 to 3.5. In addition, chief cells in the gastric mucosa secrete pepsinogen that is activated in acidic pH to pepsin and is responsible for digesting proteins and nucleic acids. Nonviral vectors must remain stable and avoid dissolution during gastric emptying, which can reach up to 120 min, depending on various conditions, including fasted or fed state. Upon gastric emptying, nonviral vectors are then introduced to the intestinal environment and a subsequent change in pH of up to 7. The intestinal lumencontains numerous enzymes, including trypsin and nucleases, making the intestine the main site of nucleic acid degradation. In the intestine, nonviral vectors must also overcome numerous physical barriers including the intestinal mucus layer, which serves to trap and remove foreign particles through normal peristaltic turnover. Upon overcoming extracellular barriers, nonviral vectors must also overcome intracellular barriers to achieve transgene expression for both gene therapy and DNA vaccination (B). For both gene therapy and DNA vaccination, nonviral vectors must first be internalized (1.), typically through various endocytic pathways that result in vector internalization into endosomes. The vector must then escape the endosome prior to endosomal acidification, and once in the cytoplasm the nucleic acid needs to dissociate from the carrier and traffic to the nucleus (2.). Finally, the nucleic acid must be internalized into the nucleus for transcription to mRNA and translation to the desired protein (3.). For gene therapy applications, additional barriers include adequate expression of the transgene to achieve a therapeutic effect. For DNA vaccination applications, targeting nonviral vectors to professional antigen presenting cells (APCs), is considered the most promising strategy. Targeting APCs introduces additional challenges, as APCs such as dendritic cells are particularly difficult to transfect.In this review, we provide an overview of recent advancements in the development of non-viral gene delivery systems for the oral route. We highlight recent improvements in material design and development that improve particle stability in the GI tract, enhance particle uptake, and increase cell targeting to increase the efficiency of orally delivered gene therapies. We then discuss applications of these delivery systems for oral DNA vaccination strategies. We also discuss some of the limitations of delivery strategies and propose future considerations in the development of oral non-viral gene delivery systems.

Oral gene delivery for gene therapy applications

Delivery of genetic materials, such as plasmid DNA or siRNA •5, •6, ••7, ••8, 9, as well as combination therapies that deliver both genetic and pharmacological treatments [10], via the oral route, have been explored for the treatment of several diseases. Oral gene delivery has the potential to treat GI tract-specific diseases, such as ulcerative colitis (UC) and cancer, as well as promote systemic therapeutic effects outside of the GI tract, e.g. to treat metastatic colon cancer, inflammation-induced hepatic injury and type 2 diabetes. Here, we highlight recent advancements in oral gene therapy, specifically various functionalization strategies to improve transfection and targeting, the use of dual material particulates to improve gastric stability, and “smart” delivery systems that are able to respond and adapt to changes in GI conditions.

Functionalization and targeting strategies to improve systemic oral gene therapy outcomes

One strategy for improving gene therapy via oral administration is functionalization of delivery vectors to improve gastric stability, enhance particle uptake, or target these systems to cells of interest. For example, mannose-modified trimethyl chitosan-cysteine NPs were designed to encapsulate and orally deliver TNF-α siRNA to reduce systemic TNF-α levels and lessen inflammation-related acute hepatic injury [6]. Chitosan (CS), a natural polysaccharide derived from the partial deacetylation of chitin, has been widely used in gene delivery. CS is uniquely suited for oral delivery due to its mucoadhesive and epithelial permeation properties 11, 12. The addition of mannose to the trimethyl-CS allows the NP delivery system to target intestinal macrophages. These NPs were found to be stable in both gastric and intestinal fluids, and oral delivery to rats with induced acute hepatic injury resulted in reduced TNF-α in the serum and diminished TNF-α mRNA levels in spleen, lung and liver macrophages compared to siRNA delivery mediated by CS NPs without the mannose functionalization [6]. The reduced levels of TNF-α also correlated with reduced disease severity in a rat model of acute hepatic injury [6].

In addition to cell-specific targeting, functionalization of delivery systems with bile acid conjugates has been investigated to enhance gastric stability and improve particle uptake by intestinal enterocytes through bile acid transporters [9]. Investigated as a method to treat type 2 diabetes, Nurunnabi et al. developed NPs of DNA and branched poly(ethyleneimine) (bPEI) that were then coated with taurocholic acid-conjugated heparin to improve oral stability and intestinal enterocyte uptake of the NPs. Oral delivery of these NPs encapsulating DNA encoding glucagon like peptide-1 (GLP-1), a stimulator of insulin secretionby pancreatic cells, was investigated as a therapy for type 2 diabetes [9]. Delivery of a single dose of GLP-1 DNA via oral gavage resulted in maintenance of normal blood glucose levels for 21 days [9]. Such sustained blood glucose levels suggests a restoration of metabolic homeostasis and indicate that other metabolic diseases (e.g. Phenylketonuria, G6PD deficiency, Pompe disease) could be successfully treated through oral gene delivery to reestablish metabolic homeostasis.

Dual material particulate systems for overcoming GI tract barriers

While NP functionalization has demonstrated improvements in the oral delivery of genetic material, the harsh conditions in the GI tract remain a major obstacle to effective oral gene therapy. To overcome these challenges, dual material particulate systems that capitalize on different material properties to both protect the encapsulated payload through gastric transit and allow for efficient delivery within the intestine, represent a promising strategy. Dual particulates were pioneered by the Amiji group and their development of multi-compartmental oral delivery systems. This system, composed of solid, protective poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL) microspheres encapsulating gelatin/DNA NPs loaded with DNA encoding the anti-inflammatory cytokine interleukin-10, was used for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in animals [13]. The PCL microsphere matrix allowed for protection of gelatin/DNA NPs, which are susceptible to enzymatic degradation, during gastric transit. Upon reaching the intestine, PCL was preferentially degraded by intestinal lipases, releasing gelatin/DNA NPs and allowing for efficient in vivo transfection. Oral delivery of the dual particulate system in a mouse model of acute colitis significantly reduced pro-inflammatory cytokines and disease severity compared to delivery of the DNA in gelatin NPs that lacked the PCL microsphere outer matrix [13].

Expanding on dual material particulate systems, Xiao and colleagues designed an oral delivery system that combined both siRNA and a pharmacological agent encapsulated in hyaluronic acid (HA)-functionalized, CS-coated poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) dual material NPs to alleviate inflammation associated with UC [10]. HA functionalization of PLGA was used to target the NP delivery system to colonic epithelial cells and macrophages of UC tissues that over-express the surface glycoprotein CD44. For this study, siRNA against CD98, a cell surface marker overexpressed on epithelial cells and macrophages in UC patients, in combination with the anti-inflammatory drug, curcumin was encapsulated in PLGA/CS NPs. Oral delivery of the PLGA/CS/siRNA system was shown to promote an anti-inflammatory environment within the gut and protect the mucosal layer in a mouse model of UC [10]. Mice receiving these particles were protected against weight loss and had lower levels of CD98 and TNF-α compared to mice that received particles containing curcumin alone, highlight to potential for gene delivery to enhance pharmacological treatment of UC.

Finally, dual material particulate systems have been investigated for improving gene therapy as a treatment for cancer. Kang and colleagues designed a dual material particulate composed of siRNA/gold NPs encapsulated in CS-taurocholic acid to treat secondary hepatic cancer caused by metastatic colorectal cancer [7]. The rationale was that addition of the CS-taurocholic acid exterior would serve to: 1) protect the siRNA from degradation, 2) provide mucoadhesive properties to the NP, and 3) promote active transport of the NPs through enterocytes via bile acid transporters [7]. Oral delivery of the NPs containing siRNA targeting the Akt2 proto-oncogene resulted in decreased expression of Akt2 in the liver, increased apoptosis of cancer cells, and tumor reduction when compared to mice treated with gold-siRNA NPs coated only with CS [7]. The ability of this system to treat cancer highlights the capacity of taurocholic acid to enhance uptake NP uptake and transport across the intestinal epithelia to promote therapeutic effects outside of the GI tract [7].

“Smart” delivery systems for oral gene therapy

Smart delivery systems that can respond to local stimulus such as pH changes or presence of endogenous enzymes represent another strategy for overcoming GI tract obstacles. These systems also allow for localized, site-specific gene delivery, which can overcome the side effects often associated with systemic therapies. For example, systemic inhibition of TNF-α via anti-TNF-α biologics(e.g. anti-TNF monoclonal antibodies) is a current therapeutic strategy for a variety of inflammatory diseases, including IBD [14]. However, reduction of circulating TNF-α by anti-TNF-α biologics injections results in systemic side effects and a limited window of treatment efficacy [14].

To overcome these limitations, knockdown of TNF-α expression locally in the gut via orally delivered siRNA is an attractive alternative to biologics with the potential to reduce off target, systemic effects. To achieve local, targeted delivery, the Peppas group designed an enzyme and pH responsive nanogel for oral delivery of TNF-α siRNA to treat IBD [8]. The platform is composed of poly(methacrylic acid-co-N-vinyl-2-pyrrolidone) crosslinked with a trypsin-degradable peptide linker. This design allows the nanogels to collapse and protect encapsulated cargo in low pH (i.e.gastric), and expand in intestinal pHs to expose trypsin-degradable cross-linkers that are degraded by intestinal enzymes to release the siRNA cargo [8]. While this platform was not tested in vivo, the nanogels did exhibit both pH responsiveness and controllable degradability. The nanogels also induced a significant TNF-α knockdown in cultured murine macrophages.

Overall, oral gene therapies represent a promising strategy for the treatment of genetic, metabolic, and inflammatory diseases, both in the GI tract and systemically. The development of various non-viral delivery systems, including NP functionalization, dual material systems, and smart systems have brought oral gene therapy closer to clinical relevancy. Nonetheless, ensuring adequate gene expression to achieve the desired therapeutic effect remains a challenge. For other applications, such as DNA vaccination, which would require much less transgene expression and as a result, less dependency on transfection efficiency, the oral route may have greater potential for clinical relevance.

Oral gene delivery for DNA vaccination

The GI tract, specifically the intestine, comprises the largest component of the immune system and is home to various populations of immune cells including antigen presenting dendritic cells (DCs) and macrophages as well as large populations of T cells and B cells, making the oral mucosa an attractive target for delivering DNA vaccines 15, 16. Oral DNA vaccination can also generate mucosal immune responses, providing important first line protection against pathogens invading at mucosal sites [17]. In addition to the harsh environment encountered in the GI tract and the presence of the barrier mucus layer, the tendency of orally ingested antigen to promote tolerogenic responses represents an additional challenge when designing mucosal delivery systems.

Functionalization strategies to enhance immunogenicity and target DNA vaccines to cells of the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissues

Strategies to improve oral DNA vaccine delivery and the resulting immune response have focused on the functionalization of NPs to: 1) enhance targeting to the cells of the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissues (MALT) responsible for antigen sampling and transcytosis [18] or 2) to improve their immunogenicitythrough the incorporation of molecules with adjuvant properties [19]. The intestinal MALT consists of a variety of immune cells that reside in the sub-epithelial lamina propria in specialized lymphoid follicles known as Peyer's patches (PP). Within the follicle associated epithelia (FAE), microfold cells (M cells) are specialized epithelial cells responsible for transcytosis of antigen from the gut lumen to underlying immune cells. Functionalization of plasmid DNA-containing PLGA microparticles with Ulex europaceous agglutinin (UEA-1) to preferentially target M cells led to enhanced systemic IgG and mucosal IgA responses compared to non-targeted particles in mice and pigs [19]. These results highlight the advantage of localizing DNA vaccines to sites of immune induction in the intestine (i.e. PPs). Similarly, Fan et al. conjugated the E. coliderived FimH protein, which has M cell targeting potential and can activate innate immune responses via toll like receptor (TLR4) 4, to CS/DNA NPs encoding the capsid protein VP1 of Coxsackievirus [19]. Compared to unconjugated CS NPs, oral delivery of the bi-functional conjugate NPs improved M cell targeting, enhanced DC maturation in a TLR 4-dependent manner, and improved protection of mice from Coxsackievirus B3-induced viral myocarditis[19]. While these functionalization strategies are promising, M cells constitute only a minor percentage of epithelial cells, accounting for only 5–10% of the cells in the FAE [20]. Targeting more abundant cells types, including immune and non-immune cell types (e.g. villous epithelial cells, dendritic cells, macrophages), may represent a more effective strategy.

Dual material particulates for protecting genetic cargo and improving immunogenicity

As discussed previously, dual material particulate systems are also a promising strategy for oral delivery of DNA vaccines to provide protection in the dramatically differing environments within the GI tract. Our group has investigated the use of the natural material, zein (ZN), in the development of a dual material particulate oral gene delivery system [21]. ZN, a prolamine from corn that is amphiphilic in nature, has good film forming capabilities, is resistant to degradation in acidic conditions, and is degraded in an intestinal enzyme-mediated manner, was used to encapsulate inner core CS/DNA NPs [21]. Oral delivery of the CS-ZN nano-in-microparticle system (encapsulating a reporter transgene) resulted in significantly higher production of mucosal IgA antibodies against the delivered transgene compared to naked CS/DNA NPs that lacked the ZN coating. These findings suggest that ZN plays a significant role in protecting the encapsulated CS/DNA cores from gastric transit, while still allowing for CS/DNA NP release and transfection of intestinal cells to generate mucosal immune responses [21]. This platform shows promise as an oral vaccine platform due to its ability to protect genetic cargo in the stomach, and allow for intestinal release of CS/DNA NPs that are: 1) stable in the intestine, 2) have reproducible transfection efficiencies, and 3) have been shown to have adjuvant properties [22].

In addition to providing DNA protection through GI tract transit, dual material particulate delivery systems are also a promising strategy for improving the immunogenicity of DNA vaccines and overcoming tolerogenic responses that are typical of orally delivered antigens [23]. In the steady state, the gut is generally regarded as a tolerogenic environment. However, if antigen is recognized in the context of a pro-inflammatory environment (e.g. inflammatory cytokines, activated innate immune cells), this response can be shifted from tolerogenic to immunogenic. Dual material particulate systems could allow for the incorporation of adjuvants (e.g. TLR agonists), either within the core particle or in the protective shell matrix, that could activate antigen presenting cells to induce pro-inflammatory conditions and lead to enhanced immunogenicity of DNA vaccines [24].