Abstract

In recent decades, distinct national approaches to engineering ethics have evolved, each tailored to its unique contextual factors. These contextual disparities make it unfeasible to transfer one country's engineering ethics approach directly into another. This calls for a compelling need to enhance our comprehension of engineering ethics within specific national contexts. This paper introduces a novel conceptual framework for national engineering ethics (NEE), inspired by Elinor Ostrom's Institutional Analysis and Development (IAD) framework. The NEE framework categorises engineering ethics activities into three core pillars: research, education, and professional behaviour. This framework facilitates a comprehensive analysis of these activities across three levels—operational, organisational, and governmental. The proposed framework offers a valuable resource for scholars seeking a deeper understanding of engineering ethics within specific national boundaries, enabling structured reporting and analysis. It serves as a critical step towards achieving mutual understanding, allowing for cross-national comparisons and the exchange of best practices. Additionally, it provides a structured platform for policymakers and developers to devise strategies for implementing engineering ethics at the national level.

Keywords

National engineering ethics

IAD framework

Institutional analysis

1. Introduction

About fifty years after the beginning of the engineering ethics boom in the United States and Europe, it has become a relevant notion throughout the world. With the growing interest in different countries, engineering ethics courses are being taught at different universities. Moreover, codes of ethics emanating from these discussions are becoming increasingly relevant in professional engineering organisations and for the practice of engineering, broadly speaking.1

While the United States, and at a later stage several European countries, have been pioneers in the field of engineering ethics, it appears that their experiences and approaches cannot be transplanted into other countries. In other words, contextual factors affect the implementation of engineering ethics in countries. Didier [1], for instance, identifies professional and educational institutes as well as intellectual traditions in ethics to be among the factors that are relevant to the local practices of engineering ethics in different countries. The question arises whether and how engineering ethics could be better understood and applied in new contexts. Recommendations and guidelines for the implementation and development of engineering ethics at the national level are needed.

While numerous efforts have been made to elucidate the evolution of engineering ethics in various countries, these studies have predominantly fixated on a limited array of factors, resulting in an absence of comprehensive analysis. For instance, in the case of Davis (1990), who delved into the surge of ethics in the United States, the focus was primarily on educational initiatives and the formulation of ethical codes, in which research aspects were overlooked. Similarly, Brumsens’ exploration of engineering ethics in the Netherlands in 2005 primarily focused on the contributions of universities and professional organisations, mostly sidelining the role of government entities and the Dutch parliament [2]. Another instance is a study on the history of engineering codes of conduct in China, as demonstrated by Zhang and Davis [3]. They concentrated on the creation and content of codes but omitted the critical aspect of how they were included in education.

There are multiple publications scrutinising distinct aspects of engineering ethics within a single country. Yet, even when collectively considered, they fail to present a comprehensive perspective due to the absence of a unifying framework for a systematic analysis. While it is understandable that individual scholars focus on specific aspects within their research, the pivotal concern is beyond the mere lack of a comprehensive per-country overview: an overarching conceptual framework can further facilitate an all-encompassing analysis of engineering ethics across countries. Such a framework would also provide a suitable basis for strategy design and policymaking and possibly provide general recommendations for the implementation and development of engineering ethics.

The goal of this study is to present such a comprehensive framework designed to enhance the understanding of engineering ethics within the national context. Our aim is to discern the constituent elements of engineering ethics and their intricate interplay at the national level, with a specific emphasis on the contextual variables that influence the localised interpretation of engineering ethics in a given nation. A primary focus of this investigation lies in examining the role of various institutions in fostering the adoption of national engineering ethics within a country.

Among the contextual factors, institutions play a pivotal and multifaceted role. Their significance lies in their ability to shape, guide, and regulate the ethical conduct and practices of engineers on both an individual and collective level. In this context, institutions (such as laws and norms) are sets of formal or informal rules that structure social behaviour and interaction [[4], [5], [6]]. These institutions are developed by and shape a wide spectrum of entities, including educational and professional organisations, regulatory bodies, and governmental agencies. Let us illustrate this with an example. Education-related institutions provide the foundational ethical training for engineers to shape their future practice. Professional organisations also follow and shape industry-specific ethical standards and codes of conduct in the form of both formal and informal institutions. These institutions provide a shared ethical framework that binds engineers together, ensuring a common understanding of acceptable behaviour and ethical responsibilities within the profession. At a higher-level, regulatory bodies and governmental agencies are instrumental in formally establishing and enforcing legal and ethical standards within the engineering profession. To incorporate the intricate role of institutions in our proposed framework, we draw upon the Institutional Analysis and Development framework, originally introduced by Nobel Laureate Elinor Ostrom (2005), as the foundational basis.

The National Engineering Ethics (NEE) framework, proposed in this paper, offers a valuable tool for identifying key elements and significant contextual factors, as well as comprehending their intricate interplay. This conceptual framework provides a structured and systematic way of understanding the landscape of engineering ethics within a specific nation. It enhances our ability to depict the developmental status of engineering ethics in a country in a more cohesive and comprehensive manner.

Moreover, this framework enables a systematic cross-national comparisons, despite the contextual disparities between different countries, thus facilitating the adaptation and utilisation of earlier national experiences in the formulation of country-specific approaches. On the one hand, this has an added value in the academic studies: i.e. scholars can benefit from an enhanced understanding of engineering ethics activities and improved documenting and reporting methods. On the other hand, the NEE framework can equip policymakers and engineering ethics developers2 with the necessary tools to leverage the experiences of other countries and to craft effective strategies for the advancement of engineering ethics within their own nation.

The paper is organised as follows. In the first section, the importance and the reason for paying attention to engineering ethics at the national level is explained. In the second section, the IAD framework is briefly described, and the reason why it is considered the method for this study is presented. In the third section, we will present the NEE Framework and describe its elements and their relationships. In this section, the components of this model, the factors affecting it and how they relate are described. Finally, in the fourth section, a working example is presented.

2. National engineering ethics, what and why?

Engineering ethics in the term national engineering ethics implies a set of activities and their outcomes in a country in the field of engineering ethics. This field includes the ethics of the engineering profession and the ethics of technology. This field includes activities related to research, education, and professional behaviour (and virtues). The educational and research activities related to engineering ethics are mainly pursued by educational and research organisations. Moreover, engineering ethics – as it is understood here - is not just a branch of philosophy or a course in a classroom; but also the professional behaviour of engineers – i.e., improving skills such as engineers’ moral sensitivity and moral problem-solving skills – is of interest. The latter is the main focus of professional organisations.

This paper specifically puts an emphasis on engineering ethics as a nationalphenomenon which could imply various concepts. Following Geertz [7], the term nation often relates to blood, race, and descent. If nation is considered a Country, it indicates geographical borders and territorial demarcation, as well as a sense of origin and belonging. Nation as State refers to political and civic loyalty to and indivisibilities of law, obedience, force, and government. Nation as Society refers to interaction, companionship, and practical association, and finally, nation as people implies cultural, historical, linguistic, religious, and psychological affinity. In this paper, national in national engineering ethics refers to a country for several practical and fundamental reasons: in our analysis, we discuss certain actions with respect to teaching, research and professional conduct; all three are best to be studied within the geographic and political confines of a country.

There are two approaches to engineering ethics. Some scholars argue for the need to strive for global engineering ethics arguing that ethics should be more and more internationalised (See, e.g., Jordan and Gray [8]). Others argue instead for localisation, emphasising specific and mono-cultural nationalities arguing that localisation is a necessary step to expand engineering ethics to new countries (See, e.g., Downey et al. [9]).

While the globalisation of engineering ethics could be useful for some purposes, such as in international engineering corporations, globalisation is not always the right approach because engineering ethics sometimes could best be understood against the backdrop of a social and cultural context of a country. For example, in engineering ethics education, Barry and Herkert [10] considered cultural factors to be effective in understanding and resolving moral conflicts and, consequently, in the complexity of education. Downey et al. [9] emphasised that an engineering identity affects engineering ethics. Didier [1] considered two factors of professional and educational organisations and intellectual traditions in ethics to be effective in engineering ethics. Therefore, without rejecting the globalisation of ethics altogether, we argue that considering some local characteristics in engineering ethics could be beneficial from an analytic point of view.

Another issue in this regard is that - accepting that localisation is justifiable - the reasons to focus on geographical boundaries of a country (as in the definition of country). To examine the state of engineering ethics in a country, is it not preferable to examine the set of countries affected by similar factors such as regions, cultures, or religions rather than studying each country individually? For example, in some of her works, Didier [1] (2015) explains the features of the European approach to engineering ethics compared to the American one. Similarly, Shuriye et al. [11] explain an Islamic approach to engineering ethics. Therefore, it may be claimed that, for example, to describe the engineering ethics in Iraq, it is justifiable to study engineering ethics in the Middle Eastern countries or Islamic approaches rather than the examination of that specifically in the geographic region of Iraq.

To answer, studying national engineering ethics is actually studying the process or set of actions undertaken in one country to achieve the goals of engineering ethics. Examples of these include the development of engineering ethics education at universities and professional organisations, the involvement of more research centres on understanding ethical issues in engineering, and writing or modifying professional ethics codes in engineering.

What develops engineering ethics in a country is the decisions and actions undertaken at different layers of power in that country. These decisions, in turn, depend on other factors that we refer to as contextual variables. It is often a government that, at the most fundamental level of decision-making, provides the do's and don'ts (i.e., institutions) by setting laws, policies, and guidelines for related organisations such as universities and professional organisations. These, in turn, are the local organisations that implement government instructions and issue executive instructions for their administrative subdivisions. Engineering ethics in countries are governed more by their governments and local organisations. Therefore, to assess the current state of engineering ethics in countries and plan its development, these authorities, their performance, and the institutions they develop should be appropriately identified and evaluated.

In order to develop engineering ethics in a country, we must inevitably examine how each of the relevant participants, from the government to a teacher or engineer, interact with each other and what institutions need to change or be created. To answer these questions, we need to look at engineering ethics within their context: the actors involved, their actions and interactions, the physical environment that affects their behaviour and the community in which engineering ethics is situated , leading to outcomes that can then be evaluated from an ethical point of view. All these can be analysed through an institutional perspective, that is introduced next.

3. Institutional analysis and development (IAD) framework

The institutional analysis and development (IAD) framework is composed of a set of actions explaining human behaviour in a complex social situation, especially for studying institutions within their social and physical environment [12]. In this paper, we inspire from this framework to develop the NEE framework as a comprehensive blueprint to organise and analyse the concepts and relations relevant to developing or implementing national engineering ethics.

The Institutional Analysis and Development (IAD) framework, as depicted in Fig. 1, serves as a structured conceptual tool designed to facilitate the understanding of complex scenarios involving diverse human decision-making and interactions. At its core, the framework introduces the concept of an “action arena,” a central element where participants and action situations come into play. Within this arena, participants engage in actions and interactions that are influenced by exogenous variables, resulting in a variety of outcomes that, in turn, jointly affect both the participants and the dynamics of the action situation.

Fig. 1

Fig. 1The action arena refers to the social space where participants with diverse preferences interact, exchange goods and services, solve problems, dominate one another, or fight. The IAD framework is therefore further unpacked to characterise action situations using seven clusters of variables: (1) participants(who may be either single individuals or corporate actors), (2) positions, (3) potential outcomes, (4) action-outcome linkages, (5) the control that participants exercise, (6) types of information generated, and (7) the costs and benefits assigned to actions and outcomes.

Exogenous variables are the factors affecting the structure of an action arena and include three clusters of variables (1) the rules (i.e., institutions) that are defined to create a shared understanding among participants about enforced prescriptions concerning what actions (or outcomes) are required, prohibited, or permitted. (2) the attributes of the biophysical world that are acted upon in these arenas, and (3) the structure of the more general community within which any particular arena is placed. Rules, the biophysical and material world, and the nature of the community all jointly affect the types of actions that individuals can take, the benefits and costs of these actions and the potential outcomes likely achieved [12].

The IAD framework suggests that the national engineering ethics activities undertaken in countries, despite their diversity and differences, have common and repetitive elements. For example, engineering ethics courses are taught in universities, governments accredit these courses, and ethical codes of conduct are published for engineers. Moreover, as mentioned, the development of national engineering ethics depends on contextual factors, especially institutions. Therefore, we need a framework that investigates institutions and other contextual factors.

By comparing IAD concepts with the aspects considered in the reports of national engineering ethics in different countries (Appendix A), it became clear that the IAD framework is able to adequately explain the national engineering context by adding further specifications.

Building on the IAD framework, we consequently categorised the information related to each national engineering action situation into certain categories and related them to each other. For instance, by considering “writing codes of conduct” as an action situation, we classified the information into groups of exogenous variables, participants, outcomes, and so on. In this case, political events, engineering events, or public demands are categorised as exogenous variables of writing codes of conduct, or engineers and philosophers who contribute to writing codes of conduct are classified as participants of this action.

In addition to the IAD framework, we used an additional theory to classify levels of analysis based on the scope of activities as the decision-making levels and activities related to engineering ethics are diverse and layered. Governments often play roles in the development and implementation of engineering ethics by setting rules for engineering ethics education or budgets for engineering ethics research. At a different level, various organisations and companies voluntarily conduct activities that influence the development of engineering ethics. For example, they write codes of conduct or codes of ethics for their employees. Lecturers teaching engineering ethics in courses can also be studied at an operational level of analysis. Each activity at these distinct levels could be affected by a different set of exogenous factors and lead to different outcomes. Therefore, considering the levels of activities in the analysis besides the IAD concepts helps us better analyse national engineering ethics in a country.

Ostrom defines four different levels of analysis: Operational Choice, Collective Choice, Constitutional Choice, and Constitutional Choice [12]. The operational choice level includes the processes regarding the implementation of operational decisions made by authorised individuals. The collective choice level captures the processes through which institutions are constructed and policy decisions are made by those actors authorised. The constitutional choice level includes the processes through which legitimising and constituting all relevant collective entities that take part in collective or operational choice processes are defined. Finally, the meta-constitutional level of analysis includes long-lasting and often subtle constraints on the forms of constitutional, collective, or operational choice processes that are considered legitimate within an existing culture [13].

In the following section, we introduce the NEE framework, which has emerged as a product of our adaptation process involving the utilisation of the IAD framework and the levels of analysis.

4. The national engineering ethics (NEE) framework

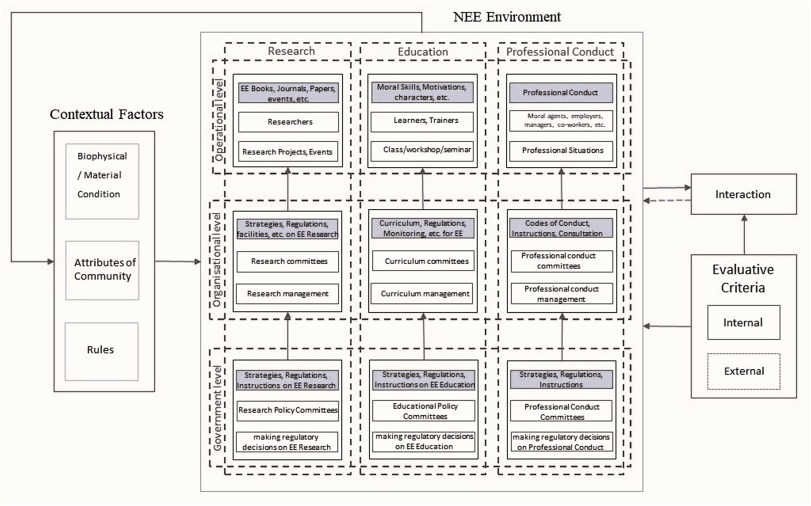

The NEE framework (shown in Fig. 2) is a conceptual map of the national engineering ethics that policymakers and developers can use to systematically understand and explain the developments in the field of engineering ethics in a specific country. This framework is a specification of the IAD framework for a specific class of activities, related to national engineering ethics. It constitutes a set of relevant components that play a role in developing engineering ethics in a country and can serve as a blueprint to better understand the current situation and as a basis to design strategies for the development of engineering ethics. This blueprint captures elements that need to be considered, and how those elements play a role in improving professional ethics among engineers.

Fig. 2

Fig. 2This section explains the NEE framework with the help of some examples. For a detailed specification of the application of this framework, the education cluster is further detailed in Appendix B.

4.1. 4-1 The NEE environment

The NEE environment captures all activities performed regarding engineering ethics in a country in a certain period. This environment has nine action arenasthat arise from classifying activities into three pillars of research, education, and professional conduct; and three levels of governmental, organisational, and operational.

The education pillar captures educational activities in universities for students, professional organisations, and other centres providing educational services. The pillar of research relates to research activities in universities, professional organisations, research centres, and individuals active in engineering ethics. Finally, the pillar of professional conduct refers to all activities relevant to professional conduct that engineering agents (individuals, groups, and organisations) undertake when engaged in engineering practices.

The NEE framework also includes three vertical levels of activities for analytical purposes. These levels are operational, organisational, and governmental. The operational level includes individuals (and sometimes organisations) who operate their tasks framed by the institutions instructed by higher-level authorities. A researcher working in engineering ethics independently, a class at a university in which a lecturer and students discuss engineering ethics, and a group of engineers engaged in a professional situation are samples of participants at the operational level. The organisational level (cf. collective level in Ostrom's multi-layer analysis) includes the decision-makings and interactions related to the establishment of instructions and strategies and the implementation of laws and regulations at the operational level. As such, the outcomes of this level affect the action situations at the operational level. Designing strategies for the studies of engineering ethics in research centres, curricula plans for engineering ethics courses in universities, and codes of conduct provided by professional organisations are some samples of the constituents related to this level. The third level of the NEE framework is dedicated to the activities carried out by governments (cf. constitutional level in Ostrom's multi-layer analysis). The government develops national laws, regulations, policies, and strategies to develop national engineering ethics in the country at a national level. The results are then passed on to affiliated organisations – the second level of the framework- as the rules to implement. Allocating funds for the development of engineering ethics in the industry, accrediting engineering ethics courses in higher education, and granting professional autonomy to professional organisations to develop their codes of conduct are examples of activities at this level (Fig. 2).

With the three pillars (education, research, professional conduct) and three levels (operational, organisational, governmental), the environment of NEE is subdivided into nine action arenas. Action arenas, in turn, are analysed under four constituents: action situation, participants, interaction, and outcome. In each action arena, participants interact with each other in action situations to achieve the desired outcomes. For instance, at the operational level of Education, action situations are classes in universities in which lecturers and students in the process of teaching-learning interact with each other to learn how they solve moral problems in their engineering practices. As an example, the Education pillar is further detailed in Appendix B.