1. Introduction

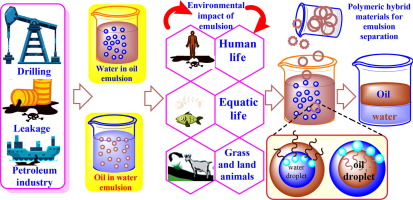

An emulsion is defined as a mixture of two or more liquids that are generally immiscible. However, in some cases, emulsifying agents are used to develop a stable emulsion. Water-in-oil emulsions are durable and commonly used in the petroleum industry [1]. Emulsions from the petroleum industry and hydrocarbon-contaminated wastewater effluents are highly undesirable because of their serious environmental consequences and adverse impacts. Crude oil emulsions are more hazardous and cause corrosion-related problems in refinery operations. The corrosion issues also cause difficulties in the transportation of oil and the heavy processing of industrial petroleum products [2]. Three methods (i.e., chemical, physical, and biological) are commonly employed for the separation of water-in-oil emulsions. The effectiveness of these techniques depends on their ability to lower the emulsion stability until separation occurs [3], [4], [5]. In the petrochemical industry, emulsions are first processed for separation and then directed to the refinery. Chemical surfactants are the most common demulsifiers for the separation of emulsions [6]. Example micrographs of water-in-oil emulsions and oil-in-water emulsions are shown in Fig. 1. In a stable emulsion, the internal phase is referred to as the dispersed phase, while the external phase is designated as the continuous phase [7], [8]. Emulsions are classified according to droplet size: ① micro-emulsion (10–100 nm), ② mini-emulsion (20–1000 nm), and ③ macro-emulsion (0.5–1000 μm). Several factors, such as emulsifying agents, interfacial tension, bulk properties, and the presence of solids strongly influence the emulsion droplet size [9]. However, the presence of surface-active agents (e.g., asphaltenes) makes the emulsion kinetically stable for a longer period [10]. The structure of a properly developed and stable emulsion neither depends on its synthesis nor changes with time because of low conductivity and small water droplet size [11]. However, the stability of an emulsion is strongly affected by the density, viscosity, surfactants and electrolyte concentration, water droplet size, interfacial tension, and film compressibility of the continuous and dispersed phases [10]. Bancroft’s rule determines the stability of the emulsion, which states that the emulsifying surfactants should be soluble in the continuous phase of the emulsion. Thus, if a surfactant shows a tendency to be soluble in the dispersed phase (water), it will form an oil-in-water emulsion. Conversely, if the surfactant shows solubility in the continuous phase (oil), it will form a water-in-oil emulsion [12]. Unfortunately, the formation of both emulsions (oil-in-water or water-in-oil) is encountered in the crude oil exploration, processing, and transportation process. This widespread occurrence of water–oil emulsions has made emulsion-based systems an important subject of investigation.

Fig. 1

Fig. 1Recently, magnetic nanocomposites with Janus, raspberry, and core shell-like structures, which are cost-effective, have been widely applied for emulsion separation [13], [14], [15]. The oil–water separation process is closely related to interfacial rheology alteration, but its complete mechanism is yet to be elucidated [16]. Therefore, an elucidated mechanism for oil–water separation as well as the selection principles for demulsifiers of light crude oil emulsions and hydrocarbon-contaminated wastewater effluents are of outstanding importance for the appropriate application of chemical surfactants [6]. Further, they will provide a basis for researchers to design and develop novel amphiphilic materials with both hydrophobic and hydrophilic characters [17] and polymers with smart surfaces that respond to external stimuli [18]. Different materials with responsive surfaces have been prepared, which are not only responsive to temperature, pH, and ultraviolet (UV) light, but also to wetting [19], [20]. These smart materials with stimuli-responsive surfaces exhibit excellent performance in a variety of applications such as the separation of oil–water mixtures [21], drug delivery [22], biosensors [23], and tissue engineering [24].

The employment of materials with smart interfaces and super wettability properties is an emerging research direction [25]. Materials with switching wettability properties are more applicable in oil–water separation and can be regarded as either oil removing (hydrophobic/oleophilic) or water removing (hydrophilic/oleophobic). Due to their excellent separation efficiency and recyclability, materials with smart wettability surfaces are superior to conventional separation materials used to treat hydrocarbon polluted wastewater and separate oil–water emulsions. Smart surfaces are defined as any material surface with the following multifunctional characteristics: ① capable of re-arranging their morphology, ② capable of retaining their composition, and ③ capable of self-enhancing their functionality in response to changes in the reaction environment. Notably, the unique switchable wettability property is effective in both “water-removing” and “oil-removing” practices. It has been demonstrated that stimuli-responsive polymeric materials that change their response according to the external condition can be efficiently used for various applications, including water purification (e.g., removal of oil pollutants, heavy metal ions, and protein biofouling) [26], [27], [28], [29], [30]. Stimuli-responsive polymers emerged as robust candidates to design and manufacture materials with unique surfaces and switchable wettability properties because of their reactive nature and excellent processability.

This review summarizes the emulsion system, environmental impacts of emulsions, and the application of polymeric hybrid materials with smart surfaces for the effective separation of oil–water emulsions. An overview of the emerging field of polymer engineering is presented through the following sections: ① emulsion system, ② background of emulsion separation, ③ conventional method of oil–water separation, ④ stimuli-responsive polymeric and hybrid materials with smart surfaces and switching wettability and their application for oil–water separations, and ⑤ comparison of different nanomaterials for controlled oil–water separation. Finally, this review concludes with future perspectives on the development of polymers with smart surfaces for oil–water separation.

2. Environmental consequences of oil emulsion

Crude oil and hydrocarbon-contaminated wastewater have severe environmental effects, which mainly depends on their production process. Moreover, the controlled or uncontrolled discharge of emulsions and wastewater to numerous water matrices create environmental hazards.

2.1. Environmental impacts of oil spillage

Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain how an oil spillage can cause damage to the environment, including:

(1) Irritation due to the ingestion or inhalation of aromatic and aliphatic components.

(2) Coating of oily products on surfaces.

(3) Oxygen depletion caused by the degradation of oil components by bacteria.

(4) Increased carbon content in seafood due to bacterial degradation.

Oil spreading to the outer environment mainly due to emulsification results in the formation of stable emulsions, dissolution, sedimentation, and chemical oxidations because of microbial metabolism via energy absorption from sunlight (photo-oxidation) [29], [31], [32], [33], [34]. Crude oil/light petroleum is volatile, contains many water-soluble compounds and floats, and can quickly spread on land or water surfaces. Thus, fresh oil can lead to more severe environmental effects as the hydrocarbons from fresh oil are easily ingested, absorbed, and inhaled [31], [33].

The composition of oil continuously changes with time, which may have highly toxic effects on the environment by leaving behind a small amount of solid, insoluble residue called tarballs that contain toxic polyaromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) [33]. During this weathering process, heavy oil mixes with water to form a stable emulsion, which is relatively more resistant to separation and slows down the weathering process [33], [35]. Further, emulsions or emulsified oil is more difficult to remove by simple dispersion, skimming, or stinging. Heavy oil and water emulsions stay in the environment for a longer period and degrade slowly [33]. It is very important to highlight that fresh oil spills transmit a large amount of saturated and reactive aromatic hydrocarbons in the dissolved and oil phases [36].

2.2. Impact on the marine environment

The effects of chemicals of different concentrations on life occur upon exposure. Oil emulsions have serious environmental impacts due to their oil and water contents, and emulsion density. Irrefutably, petroleum and petroleum emulsions are produced mostly from anthropogenic sources and have global economic importance [37]. The uncontrolled release of oil emulsions or hydrocarbon-contaminated oily water into the outer environment becomes a threat to marine life and terrestrial ecosystems such as estuarine, coastal, and deep-sea systems [38]. Offshore, damage is confined to the surface environment unless and until the crude oil is effectively disseminated into the entire column of water with chemicals [32], [34], [39]. Crude oil and hydrocarbon-contaminated wastewater can cause significant damage to coastal grass because of the dissolved toxic components that significantly pollute the aquatic environment (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2

Fig. 23. Background of emulsion separation

3.1. Liquid air wettability

The separation of water-in-oil emulsions is a wetting behavior that occurs by coating liquid on a solid surface. Wettability is an intrinsic property of a solid surface that is commonly characterized by the contact angle (CA) of the liquid droplet. In the air on a smooth and ideal surface, the liquid equilibrium CA (θ) is calculated using Young’s equation (Eq. (1)) [40]:where γSL, γSV, and γLV represent the interfacial tension at the solid–liquid, solid–vapor, and liquid–vapor interfaces, respectively (Fig. 3(a)). When the surface becomes rough with time, wetting will occur via the homogeneous or heterogeneous states. Generally, liquid covers all the voids on the surface in case of wetting in the homogenous state (Fig. 3(b)), and the Wenzel equation can be used for the CA (θW) [41]:where r represents the surface roughness factor, which is the ratio of the actual surface area and its projected horizontal area. The value of r is always greater than 1. As a result, an increase in surface roughness directly amplifies the solid surface wettability, which the lyophilic and lyophobic surfaces become more lyophobic and lyophilic. If r ≫ 1, then wettability is high, that is, θW > 150° corresponding to a super lyophobic surface or θW ≈ 0° corresponding to a super lyophilic surface. The solid/air heterogeneous interface is usually formed by the trapped air beneath the liquid droplet (Fig. 3(c)), and in this case, the Cassie–Baxter equation is used to calculate the CA (θCB) [42]:where ƒSL is the fraction of the solid/liquid interface. According to the Cassie state, the CA will be high when the air layer is trapped beneath the liquid droplet, which can be used to fabricate super lyophobic surfaces [43], [44].

Fig. 3

Fig. 33.2. Underwater oil wettability

Oil wetting mostly occurs on the solid surface in water and is related to the separation of oil–water emulsions [25]. On a smooth surface, the oil droplet forms a three-phase interface, that is, oil–water–oil (Fig. 3(d)), and the corresponding apparent oil contact angle (OCA) (θOW) satisfies Young’s underwater equation:where γSO, γSW, and γOW are the interfacial tension at the solid–oil, solid–water, and oil–water interfaces, respectively. The Young wetting state in air is also valid for both oil droplet [45] and water droplet [40] on a very smooth surface, and the corresponding water contact angle (WCA, θWA) and OCA (θOA) in air can be described by oil equation of Young’s:where γOA, γSO, γSA, and γWA are the interfacial tension at the oil–air, solid–oil, solid–air, and water–air interfaces, respectively. Thus, γSO = γSA − γOAcosθOA and γSW = γSA − γWAcosθWA are mathematically transformed from Eqs. (5), (6). Consequently, Eq. (4) can be further rewritten in the form of Eq. (7) by substituting the values of γSW and γSO:

Hydrophilic surfaces in air and hydrophobic surfaces partially in air exhibit complete underwater oleophobicity. With the introduction of roughness and heterogeneous interfaces (i.e., solid/water heterogeneous interface), the Wenzel underwater (Fig. 3(e)) and Cassie (Fig. 3(f)) states can be achieved. The Wenzel (Eq. (8)) and Cassie (Eq. (9)) states can be described with the corresponding possible OCA in water, , and :where ƒSO is for the function of solid/oil interface local area. Similar to the air situation, the Cassie underwater wetting state permit the fabrication of underwater oleophobic surface with low oil adhesion because of the water layer (oil-repellent) beneath the oil droplet.

4. Fabrication of polymeric materials and oil–water separation applications

There is a vast variety of hybrid materials which can be utilized for the separation of oil–water mixtures. However, most of these materials face problems such as incompatibility and low absorption efficiency, when used for oil–water separation or employed for the removal of hydrocarbon contamination from wastewater. Therefore, some promising materials with smart surfaces, such as magnetic materials [46], [13], [14], [15], cellulose-based materials [47], graphene or graphene oxide [48], metals and metal oxide meshes [49], and polymeric materials [50], have been developed that exhibit excellent wettability properties. In particular, smart surfaces with hydrophobic, hydrophilic, or amphiphilic characters may have more efficient oil–water separation properties [29], [51]. Furthermore, some resin-based hydride materials possess excellent characteristics in terms of oil absorption, oil retention, and reusability [52].

4.1. Membrane-based materials for oil–water separation

Both chemical structure and surface morphology affect the separation efficiency of prepared hybrid materials such as membranes and fiber-based materials. Fiber-based membranes are the most important of the separation membranes. Recently, a variety of membranes with different chemical structures and morphologies, such as cotton fibers [51], cellulose fibers, metal wires [53], carbon fibers [54], fiber-based materials prepared by electrospinning [55], carbon nanotubes [56], and metal oxide (manganese dioxide, MnO2) wires [57], have been developed that show excellent oil–water separation properties. There are many crosslinked fibers with interconnected pore structures, which can be used to design and construct different membranes. Effective separation of oil–water mixtures depend on the pore size, which can be adjusted according to specific requirements. In particular, large pore sizes may result in an effective and improved flowrate, leading to complete separation. The pores sizes can be adjusted according to the specific requirements for the separation of oil–water mixtures. To achieve high separation efficiencies and flowrates, membranes with large pores sizes are desirable. The hierarchical structure of wood, which contains many layers, is a good example for the construction of a multi-layered membrane. Song et al. [58] used a layer-by-layer assembly approach to fabricate xylem layers in a unique channel with a slurry prepared by doping geopolymer microparticles (GPs) into a sodium alginate (SA) matrix. Then, chitosan (CS) was used to transform the phloem layer into a complex and dense form. The as-prepared multilayer biomimetic membrane exists in a distinct, well-defined, and engineered hierarchy and exhibits excellent performance in the removal of hydrocarbons and other pollutants from oil–water mixtures [58]. Fig. 4 depicts the construction of GPs doped biomimetic heterostructured multilayer membranes (GHMMs) and the preparation of GPs and the GPs–SA slurry [58].

Fig. 4

Fig. 4Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) and sodium silicate (Na2SiO3) were used in aqueous solutions to fabricate macroporous materials following a single-step sol–gel reaction of trimethoxy(octadecyl)silane and hydroxyl groups [59]. A substance with a low surface energy was grafted to the macroporous materials to prepare a three-dimensional macroporous membrane with superhydrophobic properties for complete water/oil separation. Here, Na2SiO3 was used as an environmentally-friendly and low-cost crosslinking agent that can be easily produced. Furthermore, by fabricating a material with a low surface energy through strong Si–O bonds following the sol–gel reaction, the prepared porous material (PVA/Na2SiO3) showed excellent performance for water/oil separation [59]. By pressing, scratching, and pricking polyethylene (PE) powder under very harsh conditions, a polyethylene mesh was fabricated, which showed excellent performance in the separation of oil–water mixtures. The as-prepared polyethylene mesh also exhibited ultra-low water-adhesive, superhydrophobic, and superoleophobic properties, capable of destabilizing oil–water emulsions by allowing oil to pass through the mesh while retaining water. The operation efficiency persisted over multiple cycles, and the mesh remained effective even when immersed in strong acidic or alkaline solutions [60]. Moreover, a novel water-assisted and thermally-impacted method was developed to design and fabricate a skin-free superhydrophobic polylactic acid (PLA) foam with notable oil–water separating properties. The PLA foam, in which the micro- and nano-sized structure is controllable, was fabricated with different water contents. To further enhance the hydrophobic nature of the material surface, a novel and eco-friendly peeling technique was proposed to remove the smooth skin of the foam, which resulted in excellent oil–water separation [61].

4.2. Polymeric hybrid materials for oil–water separation

Polymeric materials with smart surfaces are suitable candidates for controlled oil–water separation owing to their facile fabrication process, and switchable surface wettability and stimuli-responsive properties. In particular, the strength of the stimuli response permits the chemical composition related to surface energy or chain conformation to be switched according to requirement, for example, in the design of co-polymers that are directly tuned into highly porous materials (i.e., absorbent materials or fibrous filtration membranes). Depending on the specific application, many polymeric materials with smart surfaces and stimuli-responsive properties and high wettability have been designed, synthesized, and tested to achieve controllable and efficient separation of oil and water emulsions. Table 1 [60], [61], [62], [63], [64], [65], [66], [67], [68], [69], [70], [71], [72], [73], [74], [75], [76], [77], [78], [79], [80], [81], [82], [83], [84], [85], [86], [87], [88], [89], [90], [91], [92], [93], [94], [95], [96], [97], [98], [99], [100], [101], [102], [103], [104], [105], [106], [107], [108], [109], [110], [111], [112], [113], [114] summarizes the recent development of polymer-based composite materials that are made from polymers or polymer/inorganic hybrids in different sizes, shapes, and surface morphologies for oil–water separation.

Table 1. Recent development, including fabrication techniques, of polymeric hybrid nanomaterials for oil–water separation.

| Material type | Components | Wettability | Fabrication technique | Emulsion type | Separation (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Membrane hybrid materials | Poly(dodeylmethacrylate-3-trimethoxysilyl propylmethacrylate-2-dimethyl amino ethyl methacrylate) (PDMA-PTMSPMA-PDMAEMA)/SiO2 | Superhydrophilic/superhydrophobic | In situ and ex situ treatment | Gasoline/water | 98 | [62] |

| Polytetrafluoroethylene | Superhydrophobic/superoleophilic | Self-assembly coating/sintering process | Decane/water, gasoline/water | 98 | [63] | |

| Poly(sulfobetaine methacrylate) (PSBMA) | Superhydrophilic/underwater superoleophobic | Coating/surface-initiated atom transfer radical polymerization (SI-ATRP) | Hexadecane/water | [64] | ||

| Poly(dimethylamino)ethyl methacrylate-4-vinyl benzyl chloride (P(DMAEMA-VBC)) | Superhydrophilic in air/superoleophobic | Vapor phase via initiated chemical vapor deposition (iCVD) | — | 99.8 | [65] | |

| Poly(acrylamide-co-acrylic acid)/chitosan/methacryloxy propyl trimethoxyl silane modified SiO2 (P(AM-AA)/CS/MPS-SiO2) | Underwater superoleophobic | Free-radical polymerization | n-Hexane/water | 99.5 | [66] | |

| Silica nanoparticles and decanoic acid-modified TiO2 | Superhydrophobic | Coating | n-Hexane/water | 99 | [67] | |

| Fibrous, isotropically bonded elastic reconstructed (FIBER) aerogels/SiO2 | Superhydrophobic/superoleophilic | Electrospun nanofibers and freeze-shaping | — | — | [68] | |

| Meshes hybrid materials | Styrene-acrylonitrile (SAN) nonwoven/NaOH | Superhydrophilic/superoleophobic | Controlled electro spinning/thermal treatment | Light oil/water | 99.99 | [69] |

| Polydopamine (PDA)/stainless steel | Hydrophobic | Coating/mussel-inspired/Michael addition reaction | Diesel/water | 99.95 | [70] | |

| PDA and polyethylene polyamine/copper (Cu) mesh | Superhydrophobic | — | Octane/water | 99.8 | [71] | |

| 1,8-triethylene glycoldiyl-3,3′-divinylimidazolium dibromide ([DVIm-(EG)3]Br2) | Hydrophilicity/oleophobic | One-step photopolymerization | Diesel/water, crude oil/water | 99.9 | [72] | |

| 2-Dimethylamino ethyl methacrylate (DMAEMA)/stainless steel | Superhydrophilic/underwater oleophobic | Photoinitiated free radical polymerization | Gasoline/water | [73] | ||

| Calcium alginate-coated (Ca–Alg) mesh | Superhydrophilic/underwater oleophobic | Fabrication | Hexane/water, toluene/water | 99.6 | [74] | |

| Ag-coated stainless steel mesh | Superhydrophobic/superoleophilic | Fabrication/coating | Kerosene/water, hexane/water, heptane/water | 98 | [75] | |

| Magnesium stearate (MS) | Superhydrophobic | Fabrication/substrates + adhesive + coating method | n-Hexane/water, toluene/water | 96 | [76] | |

| Polyvinyl butyral (PVB)/stainless steel | Hydrophobic/oleophilic | Electrospinning approach | Layered oil/water | 99.7 | [77] | |

| Stainless steel mesh | Superhydrophobic | Fabrication | Hexadecane/water | 96 | [78] | |

| ZnO nanowire (NW) coated stainless steel mesh | Hydrophilic/underwater oleophobic | Chemical vapor deposition/coating | Diesel/water, Hexane/water | 99.5 | [79] | |

| Sponge hybrid materials | Polypyrrole (PPy) coated polyurethane sponges | Superhydrophobic | Fabrication | Motor oil/water | — | [80] |

| Poly(2-vinylpyridine-b-dimethylsiloxane) (P2VP-DMS), melamine sponge/dopamine (DA) | Superoleophilic/superoleophobic | Oxidative self-polymerization | — | 99 | [81] | |

| Melamine, Span 80 (C24H44O6), diacrylate ester | Superhydrophobic/oleophilic | Fabrication/coating | Water/isooctane | 99.98 | [82] | |

| Polyurethane (PU) | Superhydrophobic | Fabrication/interfacial polymerization | Diesel oil/water | — | [83] | |

| Melamine, polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS)/silicone | Superhydrophobic/oleophilic | UV-assisted thiol-ene click reactions | Chloroform/water | — | [84] | |

| Melamine, isocyanate-terminated poly(dimethylsiloxane) (iPD) | Superhydrophobic | Fabrication | Hexane/water, hexadecane/water, toluene/water | 85.1–98.7 | [85] | |

| Poly(vinylidene fluoride), poly(vinylidenefluoride-ter-trifluoro ethylene-terchloro trifluoroethylene), polystyrene/polyurethane/fluoroalkylsilane modified SiO2 | Superhydrophobic | Drop-coating method | Peanut oil/water | — | [86] | |

| Poly(N-isopropyl acrylamide) (PNIPAAm) | Superhydrophilic/superhydrophobic | Interface-initiated atom transfer radical polymerization | Gasoline/water, hexadecane/water | 70 | [87] | |

| PU sponge | Superhydrophobic/superoleophilic | Fabrication | Chloroform/water | 75 | [88] | |

| Clay dust/PDMS | Superhydrophobic/superoleophilic | Kerosene/water | 98 | [89] | ||

| PU sponges/PDMS | Superhydrophilic/superhydrophobic/hydrophilic | Fabrication/simple dipping-coating method | Hexadecane/water, decane/water | 99 | [90] | |

| Polymer-based hybrid materials | DA/glass wool PDMS | Superhydrophobic | Polymerization/fabrication | Toluene, n-hexane/water | 97 | [91] |

| Polyethylene | Superhydrophobic | Pressing, scratching, and pricking | n-Hexane/water | 99.5 | [60] | |

| Poly(lactic acid) | Superhydrophobic | Template-free water-assisted thermally impacted phase separation approach with skin peeling | Dioxin/water | 98 | [61] | |

| Polystyrene | Amphiphilic | Emulsion polymerization | Chlorobenzene/water | 70 | [92] | |

| Polycardanol | Amphiphilic | Polymerization | Asphaltene/water | — | [93] | |

| Poly(2,2,3,4,4,4-hexafluorobutyl meth acrylate)-poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) | Superoleophilic/hydrophilic | ATRP | Water/heptane, water/n-octane, water/petroleum ether | 98 | [94] | |

| Vinyl-terminated PDMS copper sulfate (CuSO4)/steel | Hydrophobic | Fabrication/electro-less replacement deposition | Hexane/water, chloroform/water | 96.8 | [95] | |

| Poly(ether amine) (PEA)–PDA | Superamphiphobic | Fabrication/self-polymerization | Toluene/water, octane/water | — | [96] | |

| 2-Hydroxy-4-methoxy benzophenone (HMB), bisphenol A (BPA), bisphenol AF, 3-(hydroxysilyl)-1-propane sulfonic acid (THSP), and perfluoro-2-methyl-3-oxahexanoic acid (RF/COOH) SiO2 talc | Oleophobic/superhydrophobic | Coating/encapsulation | Span 80/water | — | [97] | |

| Polysulfone (PSF) | Hydrophobic/superoleophilic | Water-in-oil-in-water emulsion solvent evaporation | Motor oil/water | [98] | ||

| Polyhemiaminal (PHA) aerogel | Hydrophobic | One-step precipitation-polymerization | Gasoline/water | 90 | [99] | |

| Thiol-acrylate resins, 2-carboxyethyl acrylate, poly(ethyl glycol) diacrylate/SiO2 nanoparticles | Superhydrophilic/superoleophobic | Thiol-acrylate photo-polymerization | Hexadecane/water | 99.9 | [100] | |

| Polyelectrolyte-fluorosurfactant | Oleophobic/hydrophilic | Single-step polymerization | Hexadecane/water | 98 | [101] | |

| Polyurethane | Superhydrophobic/underwater oleophobic | Fabrication/coating | Hexane/water, n-hexadecane/water | — | [102] | |

| Fluoropolymers modified Kaolin nanoparticles | Superhydrophilic/superoleophobic | Fabrication | Glycerol/water, sunflower oil/water, castor oil/water | 92 | [103] | |

| Cationic polyethyleneimine | Polymerization | Heavy oil/water | [104] | |||

| PU grafted of carbon nanofiber (CNF) | Hydrophobic/superoleophilic | Dip coating | Hexane/water, heptane/water, octane/water, | 97.8, 99.8, 95.0, 96.3 | [105] | |

| Chromium (Cr), a zirconium (IV) metal–organic framework composed of six-metal clusters and terephthalic acid ligands (UiO-66), octadecylamine (OA), metal–organic framework | Superhydrophobic/superoleophilic | — | Toluene/water, hexane/water | 99.9 | [106] | |

| Natural and wood-based hybrids | Wood sheet | Underwater oleophobic | Simple drilling process | Hexadecane/heptane/water | — | [107] |

| Wood/epoxy biocomposites | Hydrophobic/oleophilic | Fabrication/coating | Diesel oil/water, hexane/water | — | [108] | |

| CS-coated mesh | Hydrophilic in air/superoleophobic in water | Coating | Hexane/water, gasoline/water, crude oil/water | 99 | [109] | |

| Chitin/halloysite nanotubes | Hydrophobic | Freezing/thawing | Hexane/water, toluene/water | 98.7 | [110] | |

| Inorganic salt-based hybrid materials | — | — | One-step Mannich-like reaction | Crude oil/water | 97.8 | [111] |

| Cu(OH)2 nanowires | Hydrophilic/superoleophobic | Fabrication | Diesel/water | 98.5 | [112] | |

| Aluminum (Al)/ZnCl2, α-Al2O3/lauric acid (C11H23COOH) | Hydrophobic/underwater oleophilic | Coating and electrochemical deposition | Hexane/water, petroleum ether/water | 98 | [113] | |

| Calcium sulfate hemihydrate (CaSO4·5H2O) | — | — | Water/transformer oil | 99.85 | [114] | |

Li et al. [115] designed a pH-responsive polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS)-b-poly(4-vinyl pyridine) (P4VP) material that exhibits pH-switchable oil/water wettability and shows effective separation of oil or water from oil/water layers by changing the pH and applied gravity-driven force. The wettability of the P4VP-containing block copolymer films displayed good pH-triggered variations because of the protonation and deprotonation of the pyridyl group. The block (PDMS) polymer possesses intrinsic hydrophobic and underwater oleophilic properties and is highly recommended for the fabrication of surfaces with special wettability properties for the separation of oil/water mixtures because of their desired attributes such as nontoxicity, elevated flexibility, and thermal stability [115], [116], [117], [118].

In addition, progress has been made in the separation of oil–water mixtures and other contaminants from aqueous media [71]. Substrates with different structures and pore sizes were successfully fabricated with polyethylene polyamine and polydopamine (PDA) co-deposition films. The self-polymerization of dopamine (DA) leads to the formation of superior adhesive films on organic and inorganic substrate surfaces in the presence of Tris [119]. The amino-rich polymer, polyethylene polyamine (PEPA), exhibits a highly hydrophilic character, is readily available at low cost, and reacts with DA via the Schiff base reaction or Michael addition between an amine and a catechol [120], [121]. Fig. 5 illustrates the preparation scheme of PDA/PEPA modified materials and their application in oil–water emulsion separation, and methyl blue and copper ion Cu2+ adsorption [71]. The generated hybrid material possesses superhydrophilic and underwater superoleophobic properties. These coated materials can effectively separate a variety of oil–water emulsions in a single step, including surfactant-stabilized emulsions and immiscible oil–water emulsions. The separation efficiency of the material was > 99.6% and high fluxes of contaminants, such as methyl blue and Cu2+, and can be effectively removed from water by adsorption when it properly permeates inside the materials. This designed method can be used on different organic and inorganic substrates for the preparation of products on a large scale.

Fig. 5

Fig. 5Progress in the single-step synthetic procedure to prepare a variety of vapor phase crosslinked ionic polymers (CIPs) via initiated chemical vapor deposition (iCVD) was the turning point. Following the design process, the monomers 2-(dimethylamino)ethyl methacrylate (DMAEMA) and 4-vinyl benzyl chloride (VBC) were added in the vapor phase to an iCVD reactor to produce a copolymer film. In the deposition process, the tertiary amine in DMAEMA and benzylic chloride in VBC undergo a nucleophilic substitution reaction to produce an ionic ammonium chloride complex, forming a poly(DMAEMA-co-VBC) ionic block copolymer film with a highly crosslinked structure. This was the first research report on the design and preparation of CIP films in the vapor phase with a large surface area and controlled thickness. The designed method does not need any additional crosslinkers. The newly-designed CIP thin films exhibited strong hydrophilic properties and can be further applied to separate oil–water emulsions [65].

4.3. Metal and metal oxide mesh for oil–water separation

A very inspiring development is the preparation of a well-designed anti-oil non-woven mesh treated by an alkali solution. pH-switchable wetting properties were achieved by controlled electrospinning of a styrene–acrylonitrile (SAN) copolymer followed by thermal treatment in an alkali solution. The as-prepared flexible and robust pH-switchable anti-oil mesh with a well-designed, 3D porous geometrical structure possessed superhydrophilic and superoleophobic properties in air. The pH-switchable surfaces can be used for the long-term separation of immiscible light oil and water emulsions using only a gravity-driven force, with excellent anti-oil characteristics and without the accumulation of any unwanted materials during multiple times of reuse [69]. The anti-boil mesh also showed tunable properties for the removal of soluble pollutants from a mixture in simple ethanol media. The robust NaOH-treated mesh was highly efficient in light oil rejection (99.99%) at a high water flux (13 700 L·m−2·h−1) and also exhibited excellent recycling stability because of the unique porous non-woven architecture with high pH-responsive agents. In situ thermal polymerization (ISTP) methods may be very useful in the fabrication of superhydrophobic hybrid materials using a single-step, so-called “one-pot,” synthesis approach. Specifically, N,N-dimethyl-dodecyl-(4-vinyl benzyl) ammonium chloride (DDVAC) was prepared and adopted as the ionic liquid (IL) precursor, and two types of polymer, DDVAC-O (prepared under air environment) and DDVAC-N (prepared under nitrogen environment), were successfully fabricated by ISTP, in air and under a nitrogen atmosphere, respectively. The successful synthesis and formation mechanism of DDVAC-O was systematically analyzed. A superhydrophobic stainless-steel mesh (SSM) was fabricated with DDVAC-OCC steel mesh (SSM-O) was fabricated with (Fig. 6) [122], and a micro/nano hierarchical surface structure was generated by wrapping silica SiO2 nanoparticles. The as-prepared SSM exhibited 99.8% efficiency for oil–water separation [122].

Fig. 6

Fig. 6The thermally-responsive block copolymer, poly(2,2,3,4,4,4-hexafluorobutyl methacrylate)-b-poly(N-isopropyl acrylamide) (PHFBMA–PNIPAAm), was synthesized by sequential photo atom transfer radical polymerization. In the next step, the prepared copolymer was directly coated on the surface of a SSM for oil–water separation under controlled temperatures [94]. The surface of the fabricated mesh can switch between hydrophobicity and hydrophilicity, owing to the combined effect of surface temperature, chemical composition, roughness, and reorientation of the functional groups. In the last step, to understand the separation mechanism, a robust material was designed to demulsify oil and water emulsions, showing hexane/water separation with a high penetration flux (2.78 L·m−2·s−1 for hexane and 2.50 L·m−2·s−1 for water) and 98% separation efficiency. Since different pollutants are serious environmental hazards, it is extremely important that dual-functioning materials are fabricated, such as the poly(ether amine) (PEA)–PDA-modified dual-functional filter material, to separate oil–water emulsions and adsorb pollutants, such as anionic azo dyes [96]. PEA and PDA were easily polymerized on a polyurethane sponge substrate via the Michael addition reaction. PEA exhibits strong hydrophilic properties and has been used as an ideal polymer for dye adsorption [123]. Polyurethane sponge was selected as a substrate because of its low cost and porous three-dimensional structure, which can amplify the wettability of the polymer coat [124]. The prepared hybrid material exhibits superhydrophilic and underwater superoleophobic properties. After the adsorption process, the material can be squeezed in a glass vessel; the prepared material can effectively separate various kinds of oil–water emulsions with high flux. Furthermore, the PEA–PDA-modified dual-functional filter material was highly efficient in adsorbing high quantities of hazardous azo dyes. Simple and scalable strategies have been reported for the fabrication of surfaces exhibiting the wetting properties of air superoleophobicity and superhydrophilicity. The spray deposition and photopolymerization of thiol acrylate resins were used to prepare nanoparticles with both oleophobic and hydrophilic chemical moieties [100]. The construction of a hydrophilic source at the interface was effectively achieved with silica nanoparticles, 2-carboxy ethyl acrylate, and poly(ethyl glycol) diacrylate. Meanwhile, 1H,1H-perfluoro-n-decyl-modified multifunctional thiol was successfully used to confer oleophobic properties [100], and various porous substrates were subsequently fabricated and employed to disrupt oil–water emulsions. Both superhydrophilic and superoleophobic properties were combined in 0.45 μm nylon membrane supports, achieving 99.9% separation efficiency and 699 L·m−2·h−1 permeate flux [100].

A polyurethane sponge with superhydrophobic properties, achieved via combined molecular self-assembly and interfacial polymerization, was found very useful in the separation of diesel oil and water emulsions. The polyurethane sponge exhibited superlipophilicity in air, super wetting characteristics, and superhydrophobicity both in oil and air, and it can effectively and selectively separate different kinds of oils to about 29.9 times its own weight [83]. Polyethylenimine (PEI) ethoxylated was selected as the aqueous-phase monomer and the oil phase monomer was 1,3,5-benzenetricarbonyl trichloride. Depending on the formation of a thick film by interfacial polymerization, the Al2O3 nanoparticles were quickly deposited on the polyurethane sponge skeleton constituting a lotus leaf-like hierarchical structure [26]. Concurrently, PEI offers a platform for palmitic acid to self-assemble through a mediated reaction in a thin film of polyamide with the help of a dehydrating agent (N,N-dicyclohexyl carbodiimide) and an amide catalyst (4-dimethyl aminopyridine). Because 1,3,5-benzenetricarbonyl trichloride can quickly react with the secondary amine of the original polyurethane (PU) sponge and the prepared thin film, the resulting film was firmly supported on the sponge surface through covalent bonds, which increases the durability and stability of the material [125]. The as-prepared polyurethane sponge exhibited excellent performance in oil absorption and reusability (> 500 cycles) for the separation of oil/water emulsions without losing their properties of elasticity and superhydrophobicity, compared to other reported works [126], [127].

5. Demulsification, eco-toxicity of emulsions, and upscale to industrial level

There are various demulsification techniques, based on chemical, electrical, and thermal methods, and entailing membrane filtration, which are briefly summarized in this part of the review. In the category of chemical methods, a variety of chemicals (chemical cocktails) have different wettability characteristics such as derivatives of fatty acids, acids, bases, alcohols, acetones, amines, and copolymers of propylene and ethylene oxides [29], [128]. Chemicals exhibiting different wettability properties, that is, superhydrophobicity, superhydrophilicity, or switchable wettability, can move to the oil–water interface and orient the hydrophilic and hydrophobic parts toward water and oil, respectively [129]. The different factors that affect the performance of chemical demulsifiers include emulsion stability, temperature, demulsifier structure, pH and salinity of the water phase, and agitation speed. Some key considerations that influence the demulsifier performance are: ① structure of the demulsifier, ② ability to distribute throughout the bulk of the emulsion, ③ agitation speed, ④ partitioning character between the phases at the interface, ⑤ ambient temperature, ⑥ stability of the emulsion, and ⑦ pH and salinity of the water phase [29], [130]. Another important factor is the concentration of the chemical demulsifier, that is, a high critical micelle concentration (CMC) may reduce the demulsifier efficiency, while an insufficient amount may not be beneficial for demulsification [115].

During the thermal treatment of emulsions, the applied heat decreases the mechanical strength of the interfacial film, facilitating the coalescence of water droplets. Both microwave and conventional heating systems are in current use, in which microwave is far better than conventional heating because the latter requires more time and labor [131]. Further, in microwave heating, the instrument can optimize the desired heating and can be modified according to the specific requirement, which is helpful in minimizing the consumption of power and decreasing environmental pollution [132]. In electrical demulsification, different currents are used, that is, direct current (DC) and alternating current (AC); pulsed or continuous. AC is a common as well as the oldest method used for emulsion separation because it is a simpler and more economical method than the pulsed method. The latter, however, is applied in the case of emulsions with high water contents and characterized by a higher droplet coalescence efficiency. When DC is applied to the emulsion, which is mainly used in the treatment of low water content emulsions, droplet coalescence is improved via the electrophoretic motion of droplets. In AC fields, however, droplet coalescence is improved by the motion that occur in the field; therefore, this type of electrical field is more suitable for demulsification [133].

A proper risk assessment of crude oil emulsions and hydrocarbon-contaminated wastewater entails a quantification of the predicted damage to the environment and its remediation. From the above discussion, it is clear that the environment does not mean a single species sensitivity. Furthermore, the proper selection of biomarkers and bio-indicators may produce a more accurate estimate of the environmental effects. Therefore, to estimate the explicit ecological risk, the data must be extrapolated to envisage impacts at the population and community level. There are many developed models to explain emulsion problems, but few of them include an investigation of the environmental impacts of fresh oil spillage in the form of a stable emulsion. For example, the Spill Impact Model Application Package (SIMAP) model reports the successful evaluation of exposure and the impacts of fresh oil spillage and its mitigation measures, acute toxicity, as well as the indirect consequences on resources such as the destruction of the affected habitats/population in terms of mortality, food source, and sub-lethal impacts. However, this model is not able to estimate the sub-lethal and chronic effects or variations in the environmental system structure and the enhanced reproductive stress and impact on survival and growth [134]. Therefore, future research should have clear directions to collect information on fresh oil spillage in the form of a stable emulsion and its possible response to single species at the community level including sub-lethal effects. This will enable the development of tools and their probable inclusion into the environmental and biological assessment of oil and hydrocarbon contamination.

Polymeric materials with smart surfaces and switchable wettability properties with excellent performance in oil–water separation need to be produced on an industrial scale. In addition, the safety measures, certified standards, and effective and accurate operation processes should be explored. The major concern should be studies on the application of these smart polymeric materials for the effective and sustainable separation of oil–water emulsions. Strategies that are more novel will be helpful in the development of new and alternative technologies to design robust functional materials for large-scale applications.

6. Conclusions and future perspectives

Emulsions or hydrocarbon-contaminated wastewater pose serious environmental impacts as discussed above with suitable examples. Emulsification and decontamination of oil-polluted water is one of the most important research subjects of the current epoch. Hence, the development of materials with multifunctional and stimuli-responsive properties, that is, surfaces with switchable wettability and anti-microbial properties, is required for oil–water emulsion separations. Oil contaminated water is a serious environmental and health issue, which becomes more challenging when the separation of highly stable and thick emulsions is required. To properly address this issue, we need to fabricate porous materials that improve the underwater oleophobicity of the material. These materials possess a high affinity for water, low surface energy, and air superoleophobicity. Interfacially-active materials with switchable wettability offer a possible remedy to the environmental problems created by petroleum emulsions and hydrocarbon-contaminated wastewater. The data presented in this review indicate that research on interfacial and wetting phenomena is mature and can be leveraged for the development of a simple solution to environmental problems caused by oil–water emulsions.

Additionally, the development of polymeric materials or polymer/inorganic composites with high mechanical strength may be a possible solution to prevent damage caused by external sources such as liquid flow, mechanical stress, and high pressure. Moreover, current synthesis procedures are the basis of mass production, creating another serious environmental issue. Thus, the development of cost-effective and simple methods is significant and pressing. Nevertheless, challenges remain, which can inspire changes in the current research paradigm, thereby resulting in fruitful achievements such as the development of materials with super-smart surfaces and tunable chemistry and microstructure, facilitating more precise design of material surface properties.

Acknowledgements

All authors are grateful to their representative institutes for providing literature facilities.